The fact that women researchers get a raw deal compared to their male peers is not news. But the extent to which the raw deal manifests itself is. And for the first time, thanks to some some extraordinary new analysis of New Zealand’s 6000 university-based researchers, we can see clearly the extent of gender inequality in terms of pay, seniority, workload and even evaluations.

… a female academic in NZ could be expected to earn $400,000 less than the men she works beside – even if she produces the same quality and quantity of research.

It goes something like this: over the course of her career, a female academic in New Zealand could be expected to earn $400,000 less than the men she works beside – even if she produces the same quality and quantity of research. In fact, even if the female academic produces more research and of higher quality she can still expect to earn less and be less likely to be promoted.

Dr Ann Brower from University of Canterbury

The work comes from University of Canterbury researchers Ann Brower and Alex James and has managed to quantify the deep systemic sexism that exists within the research sector.

Indeed, Brower and James found that a male researcher’s chances of being ranked as a professor or associate professor are more than double that of a female, even if she has a “similar recent research score, age, field and university”.

While women improved their research scores more than men, they moved up the academic ranks more slowly.

They found the $400,000 pay gap couldn’t be accounted for by research outputs and age – women with similar research career trajectories to male colleagues still get paid less. And while women, over the study period improved their research scores more than men, they moved up the academic ranks more slowly.

“I can’t say with absolute authority that it’s sexism to blame, but I can say that universities aren’t a meritocracy,” Dr Brower told BroadAgenda.

The extraordinary research – a world first – was only possible due to New Zealand’s globally unique dataset collected via the Performance-Based Research Fund that tracks and scores every individual academic’s performance in terms of quantity, quality and impact – 6000 in total.

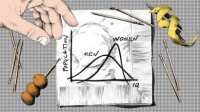

Dr Brower said the most commonly used explanation for the disparity between male and female earnings was the “male variability hypothesis” – which argues that the preponderance of older, male superstars on disproportionately high incomes distorts the average earnings upwards for all male researchers.

Dr Brower said the most commonly used explanation for the disparity between male and female earnings was the “male variability hypothesis” – which argues that the preponderance of older, male superstars on disproportionately high incomes distorts the average earnings upwards for all male researchers.

But the authors were able to dispel this hypothesis as a myth.

“We looked at only the A grade researchers – just the top 15%. Certainly, there were way more men than women but a man’s odds of becoming a professor or assistant professor are double that of a woman,” Dr Brower said.

In terms of gender pay gap, the insights are chilling.

For example, Dr Brower found that by the age of 65, a female scientist at the University of Canterbury would be earning $15,600 less than the average male scientist. Throughout her career, she would earn a total of $397,000 less than him – or what the paper says is “about 80% of the median house price in Christchurch, their home city”.

“She would need to work three additional years at her highest salary to match his lifetime earnings,” the paper says.

But worse still: “A woman who follows the higher, average male expected research trajectory will earn $194,000 less over her career than a man on the same research trajectory – about 40% of a house”.

While inherent sexism may be in play, female academics were also impacted by a “double whammy” of higher expectations from both institutions and students.

“Women’s research scores are lower, suggesting they might suffer doubly in promotions from simultaneously researching less due to higher teaching and service expectations, while still failing to meet the burden of those higher expectations,” the paper published in Plos One says.

The paper says the blame has to be laid, at least in part, with hiring and promotion practices in universities. But putting more women on hiring committees is not necessarily the solution since “bias against women is not limited to men”, as the paper says.

As the paper concludes: “Research score and age explain less than half of the approximately $400,000 lifetime gender pay gap in NZ universities. Although equity policies in hiring and promotions will narrow the gender pay gap over time, the ivory tower’s glass ceiling remains in tact.”