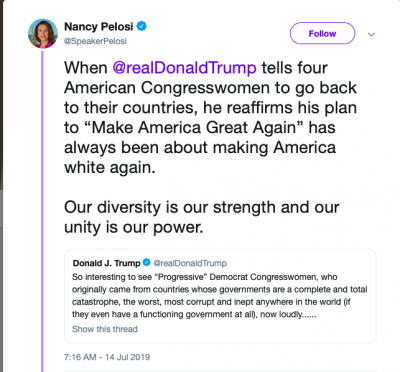

Currently, we have a global crisis of poor leadership. When Donald Trump recently attacked and disparaged female Democratic leaders with sexist and racist rhetoric, telling them to return to the “broken and crime infested places from which they came”, his spiritual UK brother, Nigel Farage crooned and cooed his approval. In Australia Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently rejected calls to increase the Newstart Allowance (an unemployment benefit which is among the lowest payment in OECD countries) on the grounds that poor people shouldn’t be supported by “unfounded sympathy”. Peter Dutton, Minister for Home Affairs discredited asylum seekers who are sexually abused in Australian refugee prisons, and argued that some are “trying it on”.

These are not edifying moments of male leaders in the global north

These are not edifying moments of male leaders in the global north. But more importantly, they serve as a blueprint of what can be said and done about women and vulnerable groups – and get away with it. Already, we have seen the cost of this blueprint – the unchecked proliferation of far-right extremists and white supremacists spewing hatred online as well as in communities; the rising inequality and intolerance; as well as the mass shooting of people who are murdered because of the colour of their skin.

The question is, what can be done about it? My research on how men stop violence against women in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Timor Leste may help shine some light on this difficult and complex topic.

My initial motivations for studying this harrowing topic stemmed from very personal beginnings. My childhood was fraught with physical and emotional violence, although I did not know that then, only that it was not a good idea to bring school friends home to play. It was only afterwards, of being removed from that context, and beginning to work in the field of domestic violence counselling, that I learned that the behaviours and values I thought were normal, were actually child abuse and neglect.

Ten years after leaving my family, I embarked on the PhD research to understand how these attitudes and norms can be changed, and how men can either choose to be a perpetrator or stand up to it. Subsequently, this also became the basis of my book, Involving Men in Ending Violence against Women.

Throughout the research I met amazing women and men, everyday heroes whose contributions and sacrifices largely go unacknowledged. Most of these people take a stand against violence against women regardless of whether there is a reward.

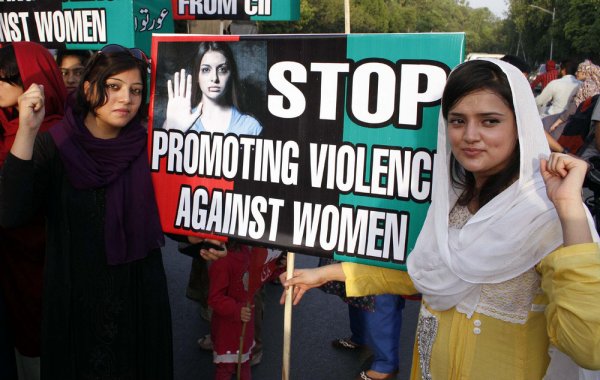

In Timor Leste, I met women working in shelters who brave daily risks of physical violence from men who feel aggrieved that shelters have ‘stolen’ their wives. In Pakistan, I met men – across religion, class and ethnicity – who reject the so-called honour killing and try to change local by-laws or help young women at risk. In Afghanistan, I met local feminists who are tired of Western donors who are always looking for ‘the next big thing’ in aid projects, and simply want respect, adequate support and independence for the work that they do.

During my fieldwork in Pakistan, I came across Oxfam GB’s programme called ‘We Can End Violence against Women’ (We Can). It managed to galvanise many people – especially men – to be activists in their community. For example, I met a businesswoman who has helped to organise anti-domestic violence marches in her town. A bus stewardess was fed up with sexual harassment, and she used the We Can campaign message to create her own anti-harassment announcements on the bus. Yet another man – a Hindu farm worker – was concerned about domestic violence in his community, and so he decided to wear We Can campaign hat at work and talk about the issue with other men.

These are inspiring stories, but they are not without cost: the businesswoman received threats of violence and the Hindu farmer was visited by a group of men sent by the landlord, who told him to stop the activism or face the consequences. Because Hindus are a minority in Pakistan, and as a working class poor person, the cost of angering your ‘superior’ can be your life.

Something which resonates with today’s global situation is the need for leaders to have moral courage and serve as models of good behaviour

There are many things that I learned during the process, but something which resonates with today’s global situation is the need for leaders to have moral courage and serve as models of good behaviour. In any community, large or small, people look to their leaders (who are typically male) on what constitutes good behaviour, but also what they can get away with.

Despite the bleak subject matter, I wrote my book from a position of optimism and hope. People essentially wish for peace and prosperity in their community, and as my research showed, men – despite being in contexts where there are immense male privileges – will do the right thing and reject violence when given tools to do so. Not because they will get a medal from western aid donors, but because they see the limitations of patriarchy. Inequality benefits some, but not all. The people I met see through that and want a better world.

As such, my message for the leaders of global north is, ask yourself ‘How did we get here, and how can we do better?’ If a Hindu male farm labourer can stand up against domestic violence in his community in Pakistan, despite limitations due to poverty and hierarchy, then what are you, as privileged First World leaders doing with all your resources and retinue of advisors? Where is your moral courage to reject the blueprint of hatred and intolerance? What sort of nation-state are you creating for future generations? Finally, what is the legacy of your leadership?

To receive a 20% discount of Dr Wu’s book ‘Involving men in ending violence against women: Development, gender and VAW in times of conflict‘, use the code FLR40.