Police are at last rethinking the wisdom of telling women in the aftermath of horrific crimes to take more responsibility for their own safety.

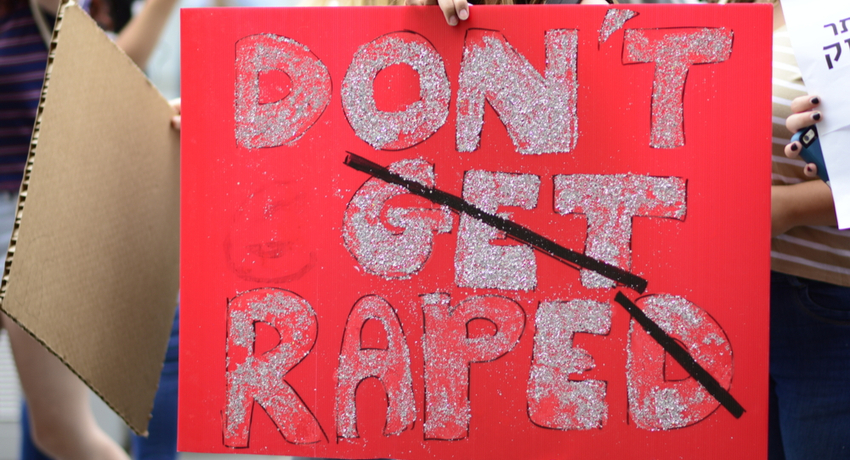

For decades, feminists have voiced their objections to rape avoidance advice, arguing that it is victim blaming. The transnational protest movement SlutWalk was created in response to a Canadian police officer’s assertion that: “women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimized”. Many lists of safety tips for women have been created by people who do not value their time or autonomy. These tips are often so vague and contradictory that they’re impossible to follow.

Again and again women insist that responsibility for rape lies solely with the perpetrators. It’s violent men who need to restrict their behaviour, not women. Boys need to be raised to treat women and girls with respect. Men need to hold each other to higher standards. But even as we call out victim blaming, many of us lock our doors and choose sensible shoes. We walk home gripping our keys in our hands.

Could there be a legitimate role for rape avoidance advice?

Could there be a legitimate role for rape avoidance advice? After all, some of the advice might be genuinely empowering. For example, researchers have shown through randomised control trials that teaching women to verbally and physically resist sexual assault is effective, and important in a culture where women are conditioned not to make a fuss, not to assert ourselves.

And while the kind of underground advice, where women warn each other to watch out for specific men, is very much discouraged by Australia’s defamation laws, it can offer protection for those who share it – even at great personal risk.

Many women can do practical things to make ourselves safer. We can’t eliminate risk, but we can reduce it. How much personal agency we each have depends of course on our power and resources – women with money and white privilege have more opportunity to avoid risks.

In a controversial article in Slate Emily Yoffe complained that feminist activists are now so fearful of blaming the victim that they deny women can take personal steps to make ourselves safer, like limiting our alcohol intake.

We can acknowledge women’s agency without blaming victims

But it doesn’t have to be either-or. We can acknowledge women’s agency without blaming victims.

With hindsight a survivor can almost always identify an action she took that formed part of the causal chain leading to her rape. For example, if she hadn’t accepted a lift with that guy, he wouldn’t have raped her. Counterfactual thinking is common among people who’ve experienced devastating events. While her choices might have produced the conditions which made the rape possible, it’s not right to think of her actions as the real cause of her rape. The blame lies with the rapist.

If we turn away from the topic of rape prevention the distinction between agency and moral responsibility is easy to grasp. Consider the case of people whose health is affected by living in a city with deteriorating air quality. Their decision to remain in the city as its air quality declines might be rational. Moving away might mean making big social and economic sacrifices they can’t afford. We can recognise their agency in choosing to stay in a polluted city, while still getting angry about the unjustness of their situation. Their decision not to leave their homes is causally connected to their respiratory problems, but the blame for their ill health lies with the polluters.

Blaming victims is just an exercise in deflecting attention

Moreover, a government body charged with environmental protection that put all its resources into blaming people for not moving away from polluted areas would be widely criticised for its mistaken focus. Why? Because there is a widely held presumption that people should be able to breathe the air where they live. Blaming victims is just an exercise in deflecting attention.

By analogy, sexual violence pollutes every part of our society. We must fight for the presumption that all people should be safe from sexual violence. Together we have a collective interest in making sure every judge and every jury recognises this as common sense.

Whether advice is legitimate depends on who is offering it. Are they using the resources and authority at their disposal to change the behaviour of perpetrators? Or are they just trying to deflect attention by telling women to have situational awareness?

The best test of the spirit in which someone is offering rape avoidance advice is how they judge women who are heedless of their advice. This is how we tell whether they are really trying to prevent rape or just intent on limiting women’s freedom.

I don’t want to dismiss out of hand rape prevention strategies directed at potential victims if they are evidence-based and easy to implement. It’s plausible that these will help some women. But they should never be a substitute for measures directed at potential perpetrators.

No one ever deserves to be raped. Victim blame does real harm. As Rebecca Stringer argues, the solution is not to deny women’s agency but ‘to de-link women’s agency from victim-blame’.

Note the above draws on the author’s published work in Women’s Studies International Forum.