Over the last 10 years global attention to LGBTI rights has increased dramatically. Alongside this we’ve also witnessed an emerging focus on gender diversity within workplaces, including within our international relations and diplomacy.

Opening up spaces for these conversations is critical. November marked the running of the first International Conference on Gender and Sexuality Justice in Asia – CoGen, held by Monash University Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur. In a region where homosexuality is still illegal or inconsistently protected in several countries, this was a surprising, but welcome, move.

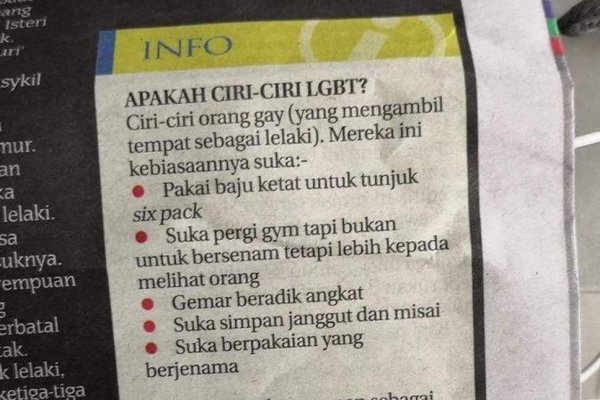

To hold this event in Malaysia was even more significant. Homophobia remains state-sanctioned in Malaysia, with homosexuality criminalised and punishable by caning. This is also reflected in the national media, with a Malaysian newspaper recently publishing an article on ‘how to spot a gay person’.

The stereotype-laden checklist on ‘the distinctive qualities’ of a gay person, published in the popular newspaper, Sinar Harian, made international news in early 2018

To participate in CoGen as an Australian LGBTI-identifying woman, and to present on the topic of LGBTI diplomacy within the Asia Pacific region, was then both a nerve-wracking and insightful experience. It presented me with a glimpse of what diplomatic work might be like for an LGBTI person operating within vastly differing social and cultural contexts.

It also highlighted the importance of being able to openly discuss issues that might be illegal, or taboo in society. In fact, instead of feeling both invisible and exposed in my identity, the space left me feeling empowered – connected to a different group of people and experiences, all looking for ways to collaborate and better our societies – suggesting that identity is soft power.

There has rarely, if ever, been much focus on the potential LGBTI women have for disrupting diplomatic spaces which are noted for their prestige, as bastions of heteronormative male privilege and dominance – least of all in a region with a high concentration of criminalisation of homosexuality, and varying levels of cultural distrust towards a deviation from sexual norms.

Both from research and personal perspectives, I was left to reflect on how identity affects diverse women’s abilities to represent their state and ‘do’ diplomacy within the region.

We know that international diplomacy is a male world, guided by norms of masculinity, and occupied by men

We know that international diplomacy is a male world, guided by norms of masculinity, and occupied by men. We also know that 85 per cent of the world’s ambassadors are men, and female ambassadors are less likely to occupy high-status ambassadorships than their male colleagues.

The Asia Pacific does have notable examples of women in diplomacy. For instance 41 per cent of diplomats from the Philippines are women. Yet the levels of legal and social acceptance vary significantly, with the criminalisation of homosexuality across Papua New Guinea, Brunei, parts of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore to name a few, and the recent worrying rise of Islamic exorcisms as conversion therapy against LGBTI populations in Indonesia. Even the more liberal Taiwan struck down a referendum on marriage equality in the past few weeks after the substantial funding of a particularly vicious anti-LGBTI propaganda campaign.

Taipei, Taiwan – Oct 28, 2017: Hundreds of thousands came out on streets for the 15th Taiwan Pride Parade. Image: Shutterstock

This environment does not bode well for LGBTI women diplomatic and security leaders operating in the region. This has crucial ramifications given that diverse leadership lowers interstate violence, builds collaboration and consensus, and delivers greater success in peace and security negotiations. Diversity is linked to improving diplomacy between nations as well as being integral to accurately representing the state internationally – the very purpose of diplomacy.

Even within Australia LGBTI women are rarely visible in high-profile and public-facing positions

It also does not bode well for visitors like myself, cautious of our identity and the spaces we take up, and more so, concerned for the space that may be taken from us because of it. Even within Australia LGBTI women are rarely visible in high-profile and public-facing positions. To be the face of their country in international relations is therefore significant. The challenges of operating in these spaces suggest that prejudice and invisibility is part and parcel of the experience.

Historically, diplomacy has been regarded as a two-person job, with the wife playing hostess to a multitude of late night events that are the mainstay of the job. This gets difficult with same sex partners and changing gender norms. In some instances, the spouses may not even be able to perform these duties due to the societal context and concerns for safety, or for the risk of potentially offending their host country colleagues and damaging relations.

Does this affect their ability to ‘do’ diplomacy? Maybe, if we regard diplomacy by the same principles of old, of which many standards are no longer appropriate – for instance, the marriage bar which prevents women from even entering diplomacy, or government in general, after marriage.

But in the same vein, representation across the spectrum of gender and sexuality, as well as ethnicity and ability, has the potential to positively ‘disrupt’ diplomacy, adding a new form of soft power to our arsenal

But in the same vein, representation across the spectrum of gender and sexuality, as well as ethnicity and ability, has the potential to positively ‘disrupt’ diplomacy, adding a new form of soft power to our arsenal. Broadening the spectrum suggests broadening our spheres of influence and understanding, both values crucial for diplomacy in the first place.

Therefore, the ability to have these positive discussions around gender and sexuality from Asia Pacific perspectives, and geopolitical contexts both sexist and homophobic, was a sign of progress. We must make sure we celebrate and support the diverse voices who can lead our international relations, and connect with more people across the spectrum.