It is time to get serious about addressing gender inequality in political representation in Australia. The way forward is to reconfigure our electoral system from the ground up.

When women won the right to vote in Westminster-style democracies they lost the struggle for better representation in Parliament. This is so for two reasons.

First, the politics of single member electorates dictates a winner-take-all approach which entrenches two-party politics and transfers power from the ballot box to the preselection committees of the parties.

Second, the vote for women legitimised a system in which it is taken for granted that men possess some form of intrinsic merit and can unquestionably represent women whereas women start from the base of having to prove their ‘merit’ to represent anyone at all.

After 100 years of the vote and agonisingly slow steps towards better representation of women, there are now renewed calls for action to be taken on gender equality.

There is no mistaking the fact that Australia has a serious gender equity problem. Australia is currently ranked 50th in the world for the proportion of women in the main chamber of the national parliament at just 28.7%.

Two issues have created an environment for reform. These are the fifth change of prime minister in eight years and the allegations of bullying and other bad behaviour exhibited towards female members of Parliament.

For many, the favoured course is to ensure that both major parties introduce quotas for equal gender representation in the preselection of candidates standing for election.

It is a mistake to rely on quotas

However, it is a mistake to rely on quotas. Instead we need to critically examine our system of representation and look to other models in our search for reform.

For the House of Representatives, Australia has a plurality system using a full preferential vote as set out in a research paper on Australian electoral systems in 2007. According to the authors this system favours the major parties; can hand government to the party with a lower vote on first preferences than its opponents and creates a winner’s bonus where roughly half the first preference vote can yield two thirds of the seats in Parliament.

Electoral systems of this type are also labelled ‘winner take all’ or majoritarianism.

A consequence in Australia is the development of instability in leadership; paralysis in policy development; entrenched adversarial-ism and dysfunctional government.

Catherine Helen Spence

This was all uncannily predicted 157 years ago in South Australia by Catherine Helen Spence when she wrote A plea for pure democracy in 1861. This was before female suffrage and even before universal male suffrage. Spence wrote about the dangers of majoritarianism in political systems based on single person electorates. She argued that such systems exclude talent so that “political life is thronged with second and third-rate men; who either have no opinions of their own, or, have the art of concealing them.” On the nature of politics, Spence said it excludes “reason from election meetings” and holds that “all is fair in electioneering” with the excuse that this is “part of the price we must pay for freedom.”

The result, according to Spence is to tempt “third and fourth rate men to make political capital by trading in popular cries, and the abuse, clamour, and unfairness of elections, combined with the personalities of newspaper attack, prevent the wise, the noble, and the worthy from offering themselves at all as candidates.”

Perhaps worst of all, politics may be immune to reform because “the fatal drawback to so-called democratic institutions is the difficulty of their reformation. It is the governing body which need the reform, who are the only means of initiating or carrying it out, and, as they will not believe they are in fault, they have never set about it.”

Our current system of politics based on single member electorates excludes talent and favours less able candidates

In other words, our current system of politics based on single member electorates excludes talent and favours less able candidates; promotes winner take all unfair tactics; encourages populism, abuse and personal attacks by media and this discourages good candidates; and reform from within democratic institutions will be blocked by those who cannot see the wrongs around them.

Gender equity quotas imposed by the political parties internally do not address the fundamental problems of winner take all politics based on single member electorates. True reform requires us to cast around for other models of representation.

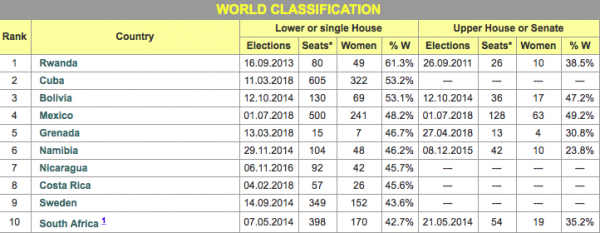

Analysis of the first 20 countries that perform best in terms of female representation in the main chamber of the national parliament shows that the electoral system itself is a critical factor. From Rwanda at number one (with 61.3% women) through to Iceland at number 20 (with 38.1% women) 80% of the top performing countries use proportional representation or a mixed system and just 20% use a plurality majority system. Australia languishes in 50th place.

Inter-Parliamentary Union: Percentage of women in the lower or single House, 2018.

Tellingly, the two parliaments in Australia that now have more women than men are the ACT and Tasmania. A major factor in achieving this result is the fact that both jurisdictions use the Hare-Clark voting system with Robson rotation of the names of candidates on the ballot paper.

Implementing a modern democratic electoral system in New Zealand has been key to its success

It is time to review our system of representation just as New Zealand did when it ditched the system of single member electorates and introduced Mixed Member Proportional Representation in 1994. This followed a Royal commission into the electoral system which reported in 1986. Implementing a modern democratic electoral system in New Zealand has been key to its success. Our neighbour has a female prime minister and a refreshing approach to developing policy consensus that Australians must marvel at.