Q. What made you choose the field you are in?

Alison: I was lucky to attend the National Science Summer School (NSSS, now NYSF) in the summer between Year 11 and Year 12. At the time I was pretty good at science and thought that I would go on to be a doctor (of medicine). By the end of NSSS I was convinced that I wanted to do research in some area of biology – most likely medical science. I enrolled in the new Bachelor of Biotechnology Honours program at Flinders Uni which gave me broad experience in different areas of biology and confirmed my interest in biomedical sciences. And the rest is a series of calculated risks and opportunities leading me to where I am now.

Jennie: I really wanted to be working with people, so I started considering something in health. Psychiatry was my first idea. Then my father hurt his back and was told he would have to undergo a lumbar fusion. He had no intention of having irreversible surgery, so he began physiotherapy instead. His physiotherapist changed his whole outlook on his injury and his own control over the outcome. She was so empowering for him, and a role model for me.

Q. What has been the biggest challenge for you in terms of pursuing your career as a woman?

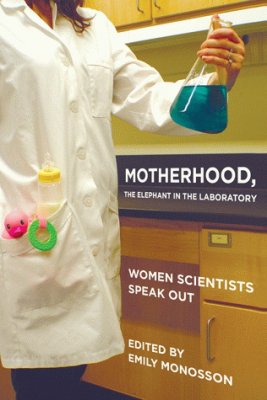

Alison: Trying to balance a demanding scientific career and a growing family has been one of the biggest challenges that I have faced. After the birth of my first child I acquired a copy of ‘Motherhood: The Elephant in the Laboratory’. Struggling to balance work and this new version of my ‘parenting life’ I hoped some insight would be provided – I was looking for some inspiring words by inspirational women who had successfully ‘made it’ as both a mother and a scientist.

Alison: Trying to balance a demanding scientific career and a growing family has been one of the biggest challenges that I have faced. After the birth of my first child I acquired a copy of ‘Motherhood: The Elephant in the Laboratory’. Struggling to balance work and this new version of my ‘parenting life’ I hoped some insight would be provided – I was looking for some inspiring words by inspirational women who had successfully ‘made it’ as both a mother and a scientist.

The bookmark still sits at page ten of the introduction and, with my children now aged 8 and 5, I continue to struggle finding that balance between my work and my life as a parent. I use the word ‘parent’ deliberately because we must not forget that men can face the same challenge.

Jennie: My biggest challenge as a woman was definitely raising children and working full time. I was the primary breadwinner when the children were small, and a single mum for a period too. It is hard to know how life would have been different if I were not a woman. I have worked half my career in hospitals, and half in universities. Hospitals are a hierarchical patriarchy. Gender issues are everywhere, from roles, to pay, to attitudes. And sexual harassment was part of the job, whether from patients or other professionals. These things are changing now, as people recognise that these behaviours are unacceptable.

Q. The research tells us that women working in STEMM related disciplines and doing STEMM related research – particularly in academia – struggle to achieve senior roles. Why do you think this is?

Alison: My working life is a constant and unbalanced tension between ‘want to do’ and ‘must do’ tasks, with a predominance of the latter. At times it can be hard to find the intellectual space that I need to be creative. I am sure this is not an uncommon experience and may be one of the reasons why the leaky pipe of academia sees many STEMM women not rising through the ranks to become a professor.

Affirmative action was successful in getting equivalent numbers of women into many STEMM areas at undergraduate levels. However, 30 years later we still have an imbalance at the highest levels of academia

Recently I joined a self-assessment team for the Science in Australia Gender Equity (SAGE) pilot, and this opportunity has challenged me to rethink gender equality and to examine what equity means to me. I grew up in an era of affirmative action for women, where policies in schools were being modified to actively promote girls into STEMM areas. This approach was successful in getting equivalent numbers of women into many STEMM areas at undergraduate levels. However, 30 years later we still have an imbalance at the highest levels of academia.

Jennie: Why do we have a blockage in the pipeline to senior STEMM roles? Gender issues in universities are more subtle than in hospitals, but they are here. Inherent biases are difficult to manage, and gendered stereotypes are hard to erase. This whole issue of men doing real work, and women just chipping in until they start a family, is an old archaic myth. We need to be call out these old attitudes when we encounter them.

Academic promotions are heavily weighted toward research publications, grants, and research leadership. Yet female colleagues ‘feel guilty doing the selfish work that is research’ when there are students who need teaching and other organisational tasks that need doing. They feel guilty shutting their door, taking their phone off the hook, or going off campus to write. How can we demonstrate that female academic leadership is valuable to the institution, and that women would be contributing to the students and the institution if they moved into leadership roles?

Someone has to lead the change. Emmeline Pankhurst would have stood up and taken the knock.

Q. What can be done about it at the institutional level?

Jennie: We need to immediately insist on gender equity on senior committees, panels and advisory groups, but this alone won’t solve it. There has been research that blinding job applications is necessary for fairness, but also that we need to make sure equal numbers of men and women apply. Women are notorious for applying for something when they have all the competencies, compared to men who will apply when they have 60% of them, so we might need to shoulder-tap or nudge women to apply.

Emmeline Pankhurst (1858 – 1928), British political activist and leader of the suffragette movement

There is now strong evidence of gender bias in publications, citations and grants successes. Deb Verhoeven in neural network analysis showed that men connect with men in grants funding. We could consider publishing under our initials – an option that did not occur to me until a mentor pointed out that it might make my career stronger. However, someone has to lead the change. I will always use my full name on my papers, even if it means less citations. Emmeline Pankhurst would have stood up and taken the knock.

The one the thing I would change right now, is insist on sufficient childcare places on campus, and include casual care there too. That was the hardest time and a breaking point for so many women.

Alison: A work place that accepts shared parenting as the norm is an essential component. In the public sector we are generally fortunate to have enterprise agreements that help to facilitate this type of flexibility, but we also need cultural change.

We also need to learn to say no at the individual level. We might be good at saying no to things that we don’t want to do, but saying yes to ‘nice to, want to’ tasks can quickly turn into too many ‘must do’ tasks. Take care of yourself, be considerate of others who are in a similar situation, if you have a family, negotiate the domestic workload with your partner, and make sure that your workplace(s) is supportive in reality and not just on paper. Once we have those elements right, it will allow a little more space for intellectual creativity, and gender equity (and diversity) will be our reality.

Let us be the change

Q. Any final words?

Jennie: We have the strength to step up. Let us be bold, let us be brave. Let us build structures for success, nurture and mentor each other and recognise that we are capable. Let us demand change. Let us be the change.