In April this year BroadAgenda published a blog by an anonymous woman about her experience of being raped as a teenager by a ‘friend’. That woman was me.

In that piece I emphasised that for every person who shares their story of sexual assault, there are countless others who won’t. And for fifteen years I was one of them.

Writing that blog came from a desperate need to share a secret I was unable to speak about. I didn’t want to go public. I was afraid of identifying myself to my friends, family, and colleagues. Yet, I felt a powerful need to unlock some of the painful details I’d kept hidden for so long. So, I did – in part.

I felt a powerful need to unlock some of the painful details I’d kept hidden for so long.

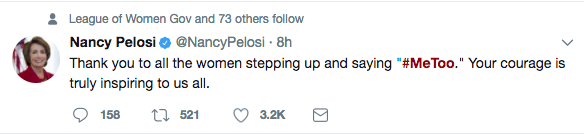

When I first saw #MeToo, I wasn’t entirely convinced that it was a good idea. As a victim of sexual violence, it made me uncomfortable. Why should the onus be on me and others like me to publicise our trauma? Why should I feel like I had something to confess?

At first, witnessing the #MeToo social media storm brought back a flood of difficult memories. But as Monday morning wore on, something changed. I started to see #MeToo appear in my Facebook feed, among schoolmates; colleagues; senior academics; people I had shared an office with for years. Suddenly, I was surrounded by people who had a story too.

At first, witnessing the #MeToo social media storm brought back a flood of difficult memories. But as Monday morning wore on, something changed. I started to see #MeToo appear in my Facebook feed, among schoolmates; colleagues; senior academics; people I had shared an office with for years. Suddenly, I was surrounded by people who had a story too.

The realisation that so many people I know had experienced some kind of sexual abuse and yet, like me, had been suffering in silence, horrified me.

I started to see #MeToo appear in my Facebook feed, among schoolmates; colleagues; senior academics; people I had shared an office with for years. Suddenly, I was surrounded by people who had a story too.

These are people who I see as strong, and not as potential ‘victims’. I am not strong. At some level I still think the assault I endured occurred because I was weak, drunk, stupid. And yet I would never assume that of anyone else. But that is the standard that I hold myself to, because this is what sexual violence does to a person’s sense of self.

It was these feelings that compelled me to post #MeToo in solidarity.

In my anonymous blog I mentioned the banality of my rapist: he was just a normal guy. The same could be said about us. We are just normal people; there is nothing about us that identifies us as victims. The more people post #MeToo, the less I stand out. I am no longer afraid of unwarranted attention, because I am not the exception, but the rule.

The more people post #MeToo, the less I stand out

As the hashtag #MeToo gathered momentum and grew exponentially, so too did my courage. I felt less afraid. #MeToo allows people to acknowledge their experience without the onus to provide detail or explanation. I hesitated to post it, but there were no questions asked, and no messages followed. It’s out there in the ether and nothing has happened as a result: all that pent up fear proved unfounded.

As the hashtag #MeToo gathered momentum and grew exponentially, so too did my courage. I felt less afraid.

Whilst some may speak, many more will not. Each of us own our stories and our trauma and we are under no obligation to speak out. Nor are we obliged to list the perpetrators: which places a burden of responsibility on victims.

There is no ‘hierarchy of harassment’, as one friend put it. Some commentators have taken issue with the #MeToo campaign by pointing out the distinction between sexual harassment and assault. But such distinction is self-evident, and doesn’t invalidate the experiences of those who suffer sexual harassment in its many forms. More importantly, the doubt we experience when we recall sexual harassment – the ‘does that count?’ – is part of what enables its perpetuation.

I recognise that #MeToo may be viewed as some kind of social media ‘flash in the pan’ which won’t result in substantial change. But Guardian commentator Jessica Valenti’s argument that “we’ve done this so many times before. Told our stories, raised our hands. Do we really need to bleed ourselves dry once again?” is misplaced. We haven’t all told our stories before; and some of us still never will. But, until now, many of us thought we were alone. Now we know we are far from alone. In fact, we are part of a crowd.

Now we know we are far from alone. In fact, we are part of a crowd.

Moreover, whilst Valenti acknowledges that sharing stories may help victims, she argues “nothing will really change in a lasting way until the social consequences for men are too great for them to risk hurting us”. This not only diminishes the value of people telling their stories, it also suggests the only way to stop men sexually assaulting women is inciting fear of punishment. Is that really the answer? I’m not so sure.

I don’t expect a revolution. But I’ve been encouraged to take another incremental step towards acknowledging and accepting my past. Whilst that may be an individual response, subtle collective transformations can happen.

Hashtags like #MeToo have the potential to carve out previously obscured discourses and exercise a kind of narrative agency that connects an affected community through the expression of their experiences – that has value.

Hashtags like #MeToo have the potential to carve out previously obscured discourses … that connects an affected community

Is this the beginning of the end of sexual violence? Certainly not. But the persistence and saturation of our stories carries a communicative power, and #MeToo may play a small role in helping some of us to deal with what I always thought of as my private, dirty secret. No longer.