In November 2015 the ARC released its Gender Equality in Research Statement, in which it acknowledged ‘the under-representation of women in the research sector in Australia’. It called upon Australian universities to acknowledge their responsibilities under the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012, and work towards becoming a Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) Employer of Choice for Gender Equality.

Over the past seven years, the Australian Research Council (ARC) has reviewed its processes and adopted a suite of policies to address the gender imbalance evident in the awarding of its grants. Change has occurred, but it’s not all good news for women.

The ARC called upon Australian universities to acknowledge their responsibilities under the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012.

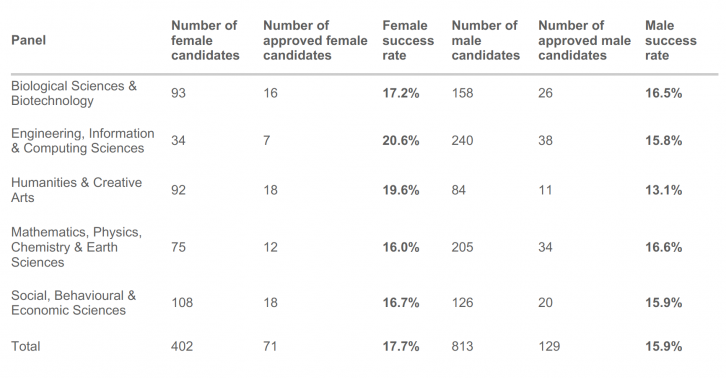

First, the good news: in the Humanities and Social Science disciplines, early career women researchers awarded funding by the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) scheme are now more successful than male researchers (see Table One).

This is a promising development with a number of inter-related causes. In 2009, a Research Workforce Strategy paper emphasised the importance of a skilled workforce for Australia’s Innovation System. A major review of the Discovery Scheme was also undertaken by the ARC’s then Chief Executive Officer, Margaret Shiel under Minister Kim Carr.

The 2010 Consultation Paper arising from the review of the ARC highlighted that the existing system was ‘biased’ towards senior researchers who were predominantly male. The data did show that after 15-20 years in the academic profession, women’s success rates in the Discovery Scheme equalled or exceeded men’s.

The review highlighted that the existing system was ‘biased’ towards senior researchers who were predominantly male.

However for early and mid-career academics, the opposite was true. It was thought that early career researchers as a group were having difficulty establishing independent research and teaching careers. The DECRA award scheme was therefore established as a result.

Another new policy termed ROPE – Research Opportunity and Performance Evidence – was introduced to acknowledge academic career interruptions, and replace the old selection criterion of ‘track record’.

ROPE was designed to provide guidance to applicants and to assessors; applicants are now able to outline their research outputs and experience in the context of their opportunities for research. While family and carer responsibilities, including career interruptions, could limit the opportunity to undertake research, a ‘research only’ role may enhance opportunities.

A female early career researcher undertakes an experiement.

The focus of ROPE is on the quality rather than the sheer volume – or lack thereof – of research outputs, as assessed through rigorous peer review. Increasingly, career interruptions working with industry and end-users, such as non-government organisations, were also to be taken into account across all ARC schemes, especially with Linkage grants, which encourage collaboration with partners outside of the university sector.

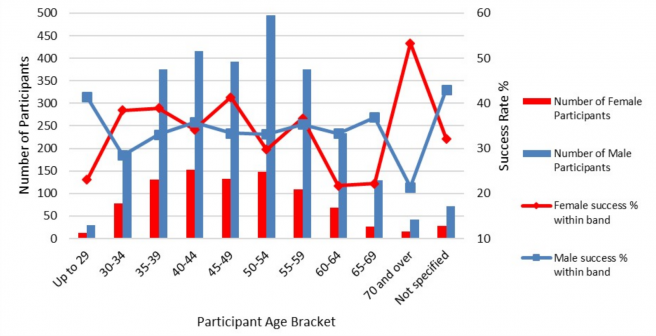

As a result, in the outcomes of Linkage 2015-16 round show that overall women’s success rates matched men’s. In fact for applicants in their 30s, women were more successful than men.

The focus is now on the quality rather than the sheer volume – or lack thereof – of research outputs.

Now for the bad news: In Science, Technology and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines, and to a lesser extent in the Social Sciences, including Economics, there is a relative shortage of women applicants for the DECRA scheme. For example in the Engineering and ICT panel the number of successful men was higher than the number of women applicants! (see Table One).

Similarly, men are almost three times as likely as women to lead Linkage Projects. This can be partly explained by the greater volume of applications in the STEM disciplines, where there are fewer women compared to Humanities and Social Science. In 2016 for example, three quarters of applicants were in STEM.

Men are almost three times as likely as women to lead Linkage Projects.

This demonstrates that there is more work to be done to address the imbalances that exist within the university sector, and within the STEM discipline in particular. However there may be other factors involved that explain why women aren’t coming forward as research leaders, such as the relatively small number of women applicants in the leadership age bracket of the 50s (see Table Two).

One promising result of the implementation of the ROPE policy within the ARC selection processes is the extent to which university leaders now talk of research opportunity, rather than the old-style track record that was biased towards those with uninterrupted full-time careers, who are mostly men.

I am hopeful that in coming years these ideas will trickle down into the selection and promotion policies within universities and research institutes – and even to industry partners in the Linkage suite of schemes. The policies adopted by the ARC, while not a cure-all, point to the potential for policy changes to positively affect change at the structural level.