For many scholars of political leadership, authority is the central concept that helps explain when presidents or prime ministers succeed and when they fail. In Western democracies such as Australia, leaders are granted the authority to use the powers of their office by a variety of other people: by political actors both within their parties and within parliament, by interest groups and organisations that will either endorse or oppose leaders’ actions, and by the public, whose attitudes towards prime ministers encourages politicians either to support or oppose political leaders.

When authority is limited, Australian Prime Ministers become increasingly unable to act, are unlikely to achieve many of their legislative ambitions, and are typically viewed as unsuccessful leaders. This has grave implications for women in leadership, who are less likely to be granted considerable authority than men in similar circumstances. Arguably, various recent trends in Western democracies, including Australia, are further weakening the hand of leaders with lesser authority.

Authority and women in political leadership

Although there are many definitions of authority in politics and many aspects to political authority that are relevant to political leaders, here we are most concerned with authority as the capacity to legitimately exercise power.

Often, more—or less—authority will be granted to political leaders as a result of the social and political climate in which they lead. For example, the much celebrated Australian Prime Minister John Curtin was granted towering authority in large part because of the national struggles of World War II. This allowed Curtin and his successor Ben Chifley to establish far-reaching changes to Australia’s economic policy.

Other leaders without unifying national and international events, and particularly those who lead parties divided about the best course of action for the country, are far more constrained, and struggle to garner support even for more limited action. Of course, authority is always granted within certain limits, and gaining and maintaining authority is not solely about historical circumstances, but is also gained through political skill.

Unfortunately, the concept of authority in political leadership is highly intertwined with masculine ideas of commanding leaders, who dominate the politics of their nation. Social psychological research suggests that people are more likely to grant political authority to male leaders than to female leaders.

The concept of authority in political leadership is highly intertwined with masculine ideas of commanding leaders.

This is most likely because of implicit societal understandings of what leadership should look like, which have developed in part because for thousands of years men have more frequently occupied leadership positions.

The good news is that as women are seen in more and more leadership positions throughout society, this association will diminish. However, while there is undoubtedly some slow progress in this regard in Australia, a number of recent trends here and in other democracies potentially diminish advances made against the authority problem for women in leadership.

Negative authority trends: ousting the leader

One of the major recent trends in Australian political leadership is that when either major party is consistently behind in political polling, an alternative leader from within the party seeks to challenge, and replace, the incumbent. This trend has been apparent in both major parties, particularly since the mid-1980s, with eight Opposition Leaders and four Prime Ministers either losing a mid-term leadership contest, or resigning under pressure, since 1985.

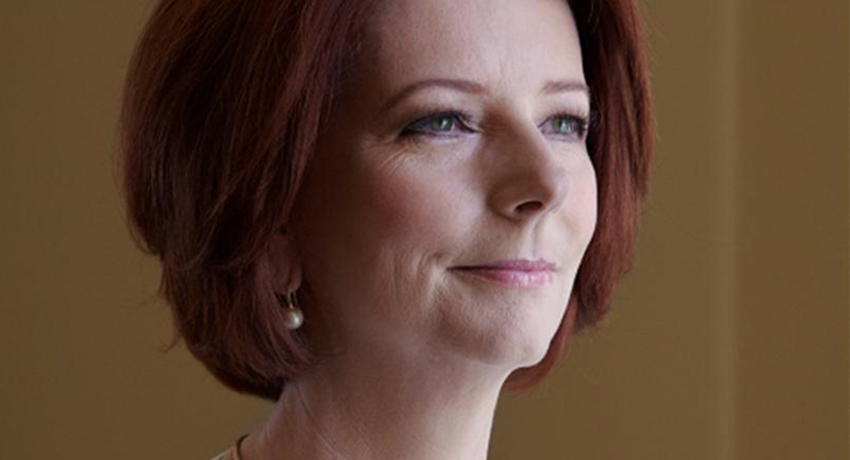

The need for political leaders in Australia to be willing to oust their predecessors has particular consequences for the authority of women in leadership, as was demonstrated when Australia’s first female Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, pressured Kevin Rudd out of office.

The media and public reaction to Gillard’s deposal of Rudd was particularly severe, when compared with that of other leaders in similar situations, and the language used to describe Gillard’s actions was overtly gendered. Even in the usually more politically correct Fairfax newspapers, one opinion piece the day Gillard became Prime Minister began with the phrase, “Nice girls don’t carry knives”.

“Nice girls don’t carry knives”

This was part of a consistent media narrative that emphasised how Gillard’s actions were incongruent with stereotypical expectations of women’s behaviour. It is consistent with a large body of research showing that women who seek power tend to be viewed negatively, unless they can overtly display stereotypically feminine communal behaviours at the same time.

Additionally, the trend towards ousting the leader creates particular challenges for women who are already in power. In a study of 11 parliamentary democracies, O’Brien (2015) found that where women are the incumbents, any electoral decline is more likely to result in their replacement than a similar decline under a male leader.

Australia’s trend towards deposing leaders is unlikely to work to the advantage of women. Those women who depose their predecessors may begin with a specific authority disadvantage because of their failure to meet gender stereotypes, and are unlikely to be well-served by a culture of ousting the leader when they are the incumbent.

Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd looks at his successor and predecessor Julia Gillard during during a Parliamentary session.

Negative authority trends: Times of uncertainty

The finding that women are more vulnerable to being ousted from leadership positions accords with the general reality that, all other things being equal, women in leadership are granted less authority than men. This is of particular importance at this current moment in history.

While historical circumstances can be a source of increased authority for political leaders, at this time, current conditions in Australia and other Western democracies tend to limit political leaders’ authority.

Recent developments in Western democratic societies have generally seen a decline in traditional groupings that past leaders have relied upon to build support for specific courses of action. Where past leaders used consistent groupings of unionised workers, or church-goers for support on specific issues, membership and involvement in these institutions has declined substantially, and has not been replaced by other large or coherent groupings.

Members of the public are less inclined than ever to join political parties, and to provide consistent support for a party or ideological agenda. Instead, people are more likely to approach politics as individuals, choosing to engage in certain issues, rather than providing consistent support for a variety of ideologically-defined issues.

People are more likely to approach politics as individuals, choosing to engage in certain issues, rather than providing consistent support for a variety of ideologically-defined issues.

This means that mobilising support for an issue is still possible, but that mobilising support for a large, complex agenda is far more difficult. Without this consistent support, leaders are unlikely to be able to wield the authority that historically successful prime ministers like Bob Hawke or Robert Menzies were able to.

The rise of social media has also altered the public’s interactions with political leaders. The nature of responses to leaders’ actions via social media mean that users are able to read, hear, and see public reactions to events instantaneously. Complex political messages can also be countered with ridicule and personal vitriol.

Where that vitriol is directed against women in leadership, it frequently takes on an overtly and aggressively sexist character. Such instantaneous attacks do nothing to enhance the authority of leaders, meaning that their opportunity to gain support for a position is often limited to a very short period of time.

John Curtin, Australian Prime Minister from 1941-1945, addresses the nation during World War II.

Another trend diminishing the authority of political leaders is the heightened global sense of political and economic uncertainty of the last few years. The pro-free trade and pro-market ideology that has dominated most Western democratic nations since the 1980s has increasingly come under question for its tendency to exacerbate inequality within these countries, and because of the sluggish economic performance of many of these countries in the past ten years.

However, while these once dominant ideas are flagging, there has been no coherent viable alternative offered, which means that leaders coming to power now cannot be sure of the best course of action for their nations.

Far from the era of Curtin-Chifley, or Hawke-Keating, where the shortcomings of traditional economic approaches were apparent, and an alternative was available, today’s national leaders are fumbling in the dark, lacking a convincing and coherent direction that they can use to unite their societies, and garner authority.

The authority challenges of this historical era affect political leaders whether they are male or female. However, these challenges are particularly acute for women in leadership, as we know that women are granted lesser authority than men even in these same constrained circumstances.

The authority challenges of this historical era affect political leaders whether they are male or female.

This means that for all the (slow) gains we are making in ensuring that women can reach national positions of political leadership and can be granted significant political authority, these developments are making the authority problem for women in leadership more difficult.

With no end to these problems in sight, it seems that it may be some time before Australia has a female prime minister who is lauded in the same way as iconic male prime ministers such as Hawke, Menzies and Curtin.

References

Hall, L. J. and Donaghue, N. (2013) ‘‘Nice girls don’t carry knives’: Constructions of ambition in media coverage of Australia’s first female prime minister’. British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 631-647.

Mendelberg, T. and Karpowitz, C. F. (2016) ‘Women’s authority in political decision-making groups’. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 487-503.

O’Brien, D. Z. (2015) ‘Rising to the Top: Gender, Political Performance, and Party Leadership in Parliamentary Democracies’. American Journal of Political Science 59: 1022-1039.

Rudman, L. A. and Kilianski, S. E. (2000) ‘Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Female Authority’. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26: 1315-1328

Sawer, M. (2013) ‘Misogyny and misrepresentation: Women in Australian parliaments’. Political Science 65: 105-117.