Demonstrably women in senior positions are held to higher standards and subjected to a more muscular critique than their male counterparts. The higher the post, the fewer the women: so every aspect of their presence and behaviour is under greater scrutiny.

Demonstrably women in senior positions are held to higher standards and subjected to a more muscular critique than their male counterparts.

But has there been a “serious regression” in the public treatment of women, as Triggs suggested last week? Are we indeed going backwards when it comes to the treatment and representation of women in leadership? And if this is true, what are the implications for Australian democracy?

First, let’s look at what happened to Triggs in what one journalist referred to as “her final chaotic appearance” at Senate estimates (which I’m sure she’ll miss enormously). Let’s just be clear about that charge of “chaotic”. Love or loathe her actions (which are the two extremes women such as Triggs excite in commentators) there was nothing chaotic about how the Human Rights Commissioner presented herself, or answered her interrogators.

There was certainly chaos reigning around Triggs as the Senate’s legal and constitutional affairs hearing into Budget matters descended into farce. Chair of the Committee, LNP Ian McDonald, bellowed at Greens Senator McKim to leave the hearing, to which the recalcitrant MP replied “I’m not going. What are you going to do about it?” McDonald huffed and then McKim puffed, “You are a tyrant and a dictator.” (McDonald was later forced to admit he had no power to order anyone out of the hearing). Throughout all this shouty nonsense Triggs remained calm, professional and focused. Far from “chaotic”.

Nor was she “eager to portray herself as a victim”, as another journalist suggested. Rather, Triggs stated what we all know: “There has been clear evidence that women in senior positions or women in the media are being attacked.”

As a journalist with over 25 years reporting and presenting television news and current affairs across commercial and public broadcasting, I’ve watched the changing nature of media representations of women from uncomfortably close quarters. I’ve argued and been shouted down countless times. Some were unwinnable arguments: such as threatening to call a media strike over the photo depiction of a near naked woman crouched on all fours, wearing a dog collar, on the cover of a Kerry Packer magazine. I was told by my then boss to remember who paid my salary (It was Packer). End of story. Other arguments were more effective and caused a rethink about the imagery we used when editing stories, and resulted in collective efforts to stop lazily resorting to gender stereotypes.

Some were unwinnable arguments: such as threatening to call a media strike over the photo depiction of a near naked woman crouched on all fours, wearing a dog collar, on the cover of a Kerry Packer magazine.

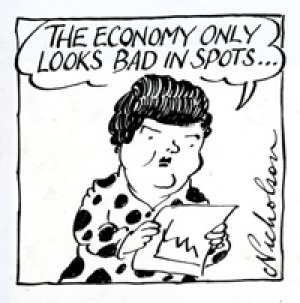

There were very few women in high profile journalism roles in the early 1990’s, when women were largely treated as an amusing curiosity in public leadership positions. Media made a headline fuss about ‘firsts’: Carmen Lawrence and Joan Kirner were blitzing the airwaves as the ‘first female’ State Premiers, pulling bullish press gallery blokes into line for using aggressive language. Kirner even turned cartoon images of herself as a frumpy, pokka-dot frocked housewife into a badge of honour. Who can forget her ‘spot on Joan’ campaign! And back in the studio, the most powerful woman in commercial TV brought a prime time show to its apologetic knees when she refused to go on-air following a story about topless barmaids. (Word was that Packer apologised personally).

I’m not for a moment suggesting women in public life had it easy – but there was a time when the positive power of women in leadership held some promise. Around 1991 the Labor Pollster Rod Cameron spoke glowingly about a shift towards the “feminisation of politics”. There was a sense that women were beginning to seriously crack the glass ceiling and there was an element of respect – albeit begrudgingly – for those who actually made it through to the other end. Until… until… it seemed there might be too many break-throughs. And ambitious women with pointy elbows were suddenly getting in the way.

“…there was a time when the positive power of women in leadership held some promise.”

In the three decades I’ve been collating lists and keeping a gender tally, Australia has unquestionably seen an increase in the representation of women in public and political leadership. Back in 1984 when the Sex Discrimination Act became law, sending a genderquake through workplace cultures, Susan Ryan was the lone woman in Cabinet (as was Julie Bishop in 2013); there were only 19 women in federal parliament (and 170 men); and no women heads of Commonwealth Departments. Now, 33 years later (!) there are 74 women in federal parliament (152 men); and 6 female Department Secretaries (and 12 male).

I could go on quoting numbers, as yes numbers matter – which is why I left my media role to head up the 50/50 by 2030 Foundation. However, the numbers don’t matter as much as the actions associated with them. What actually happens to women when they actively and assertively take over leadership roles once reserved for men and considered ‘male’ domains is where the gender equality project is coming unstuck.

Professor Deborah Rhode nailed it at the completion of an exhaustive study when she said, “An overview of more than a hundred studies involving evaluations of leaders indicates that women are rated lower when they adopt masculine, authoritative styles.”

We saw this played out daily when Julia Gillard became Australia’s first female PM, and brought 6 other women into her Ministry.

But despite the historic dimension to her public achievements, Gillard’s body, the colour of her public hair, her womb, her fertility, and her sexuality all became ‘fair’ game, as the Prime Minister’s ‘femaleness’ took full focus, well beyond any policy failings. Dame Quentin Bryce, as Australia’s first female Governor General also copped a media backlash from the moment she dared wear bright colours and floral frocks onto the world stage.

Since Federation this role had been reserved for men in dark suits, or military brass. What on earth do we do with a Governor General and Commander in Chief who wears fuchsia lipstick? Despite presiding over more events, meetings and forums than any other GG in Australia’s history, the media response to Bryce was mostly an obsession with her clothes. Or befuddled by her ‘difference’ many chose to simply ignore her presence… and wait for the brass to return. Which it dutifully did.

In my cub reporting days’ women on television weren’t publicly rated as “hotties”, and not even the worst among my male colleagues would have dared call Joan Kirner a “bitch” or a “lying witch”. And the US President, Ronald Reagan, would never have survived a pussy grabbing boast without his own wife crucifying him.

As more women brace themselves for public leadership in Australia, the game rules have changed. Where competence and qualification are no longer in question – there is nothing to stop women stepping up and taking charge – except, sadly, a well-grounded fear of being torn apart limb, by female limb. Right now, post Gillard, Bryce, and in an era of pussy-grabbing acceptance, the unrestrained abuse of high profile women we witness across mainstream and social media is our new ‘norm’. By refusing to strenuously call it out – we condone it.

This is the “regression” to which Triggs was referring. And this is the dilemma for Australian democracy. Whilst we do nothing to improve media representation and public perceptions around female leadership we are in jeopardy of languishing even lower in the global gender gap index, whilst also sending a miserable message to young women that suggests gender equality cuts out mid-career. And beyond that – they’re on their own.

We will never be truely democratic, nor representative, whilst our public leadership remains heavily weighted in favour of men.

Virginia Haussegger is Chief Editor of BroadAgenda, and Director of the 50/50 by 2030 Foundation, at the University of Canberra.