The Northern Territory is in the midst of a landmark inquiry into the murders of four Aboriginal women. The inquest has repeatedly heard of a system in crisis: women’s shelters do not have enough beds, staff salaries are being reduced due to lack of funding, and police call-out times have more than doubled.

During the coronial inquest into R. Rubuntja’s murder, the counsel assisting the coroner, Peggy Dwyer, read out a working paper from the Northern Territory’s Interagency Coordination and Reform Office (ICRO). This paper outlined that domestic, family, and sexual violence (DFSV) currently costs the Northern Territory in excess of $600 million per year. They therefore pitched a conservative budget bid of $180 million over five years to fund the Northern Territory DFSV sector.

They acknowledged that a long-term funding cycle is important to support the long-term work to prevent and address DFSV in the Northern Territory. Yet despite the high and severe rates of DFSV in the Northern Territory, the ICRO was advised to revise their bid to $90 million over 5 years, before, finally, the Northern Territory government committed to only $20 million over two years.

This meagre funding commitment was read aloud to me whilst I was on the stand providing expert testimony on the systemic issues that allowed R. Rubuntja – a founding member of the Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group – to slip between the cracks of a system in crisis. It was a terrible way to find out just how little our government values the lives of women and children. It also reiterates why the Commonwealth government must step up and commit to needs-based funding for the Northern Territory.

Domestic, family, and sexual violence is frequent and severe in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory has some of the highest rates of domestic family and sexual violence both in Australia and in the world. According to the latest data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the 2021 victimisation rate for assault in the Northern Territory was the highest in the ABS’ twenty-seven year time series.

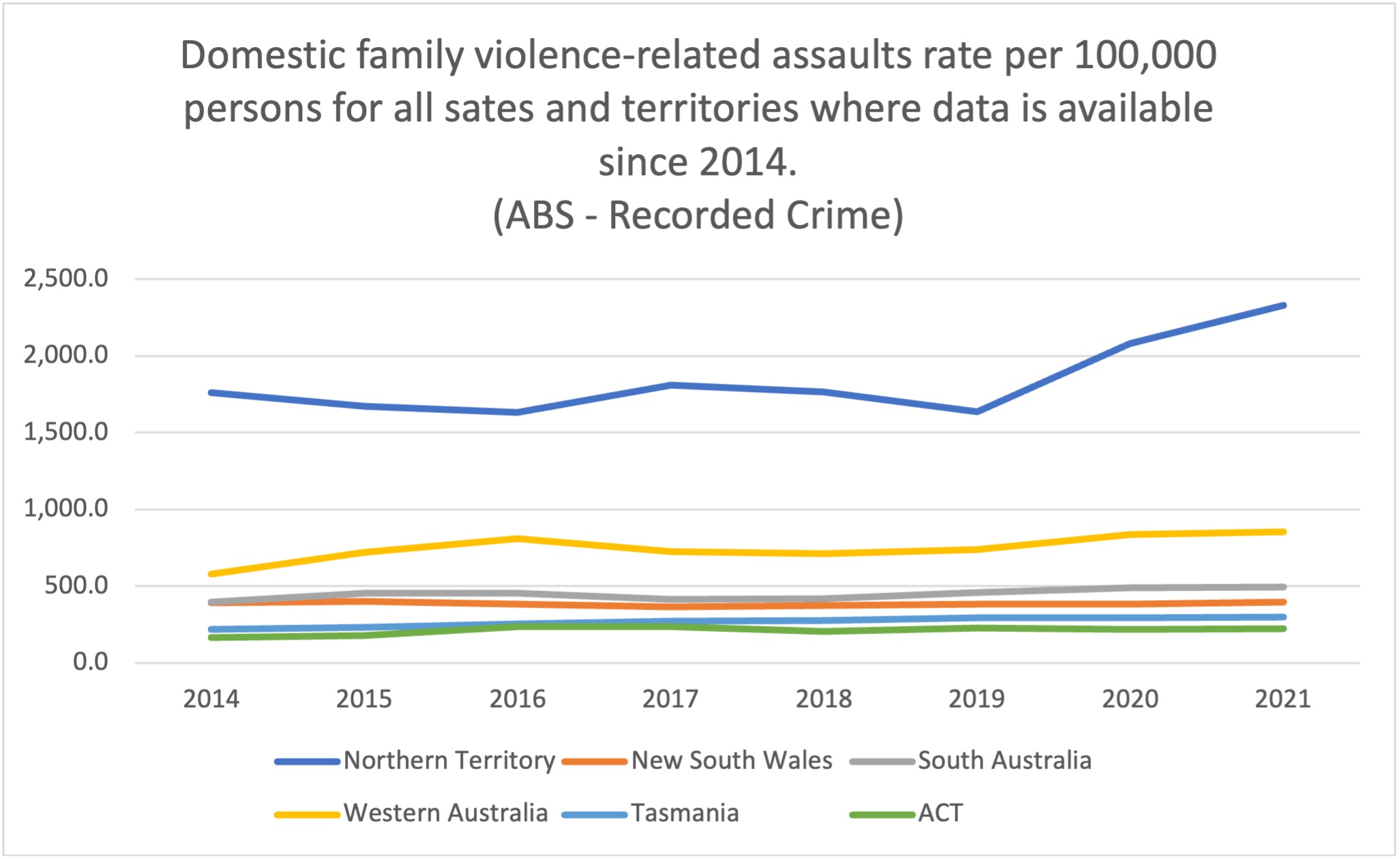

The ABS data shows that 63% (almost two-thirds) of assault victims in the Northern Territory are female, and 63% (almost two-thirds) of assaults are related to domestic family violence. The rates of domestic-family violence related assault in the Northern Territory were three times the national average, and five times that of most other jurisdictions where data is reported. Figure 1 shows that that rates of domestic family violence-related assaults have remained substantially higher than other jurisdictions where data is reported over time.

Figure 1 Domestic family violence related assaults per 100 000 over time

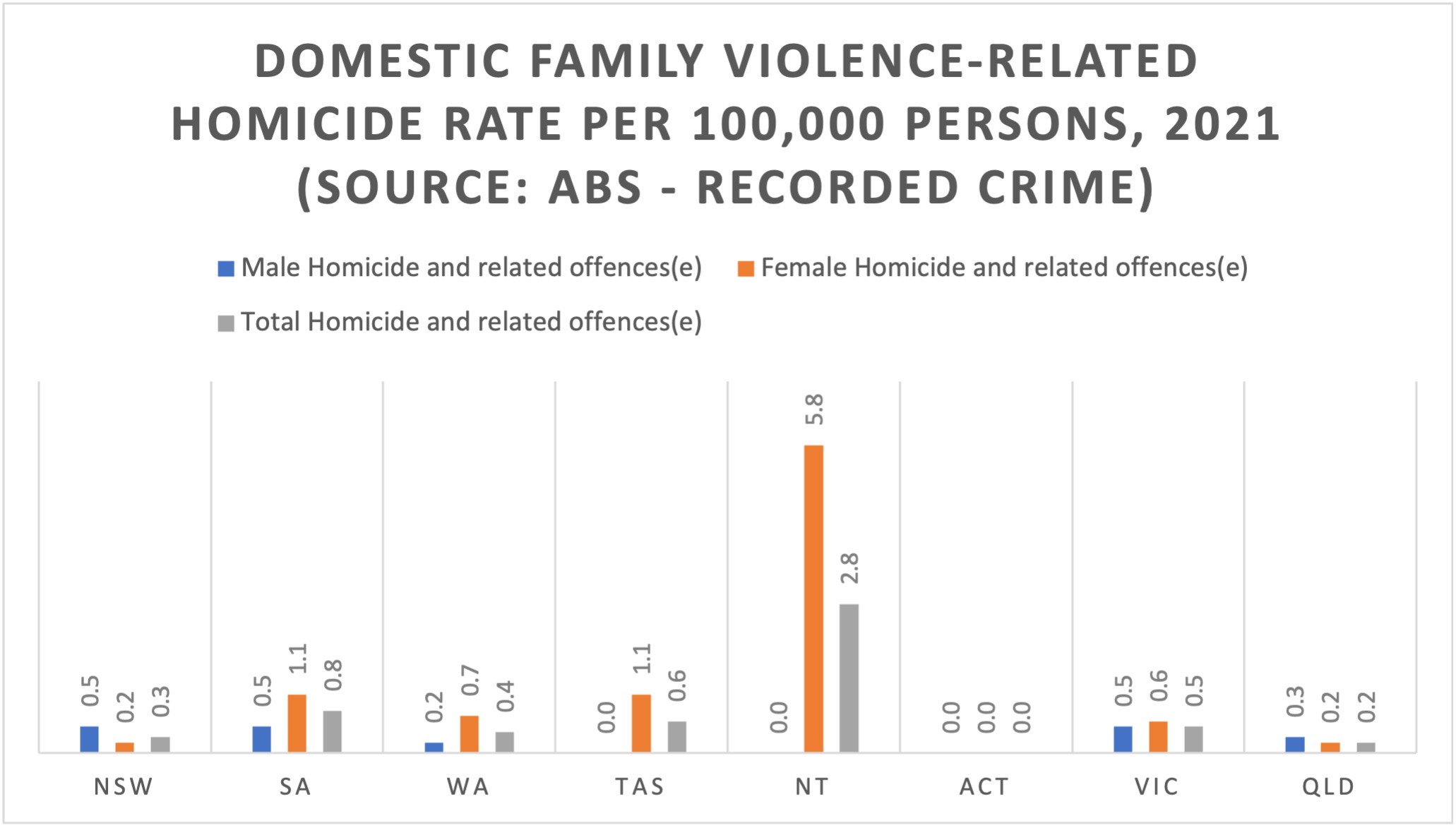

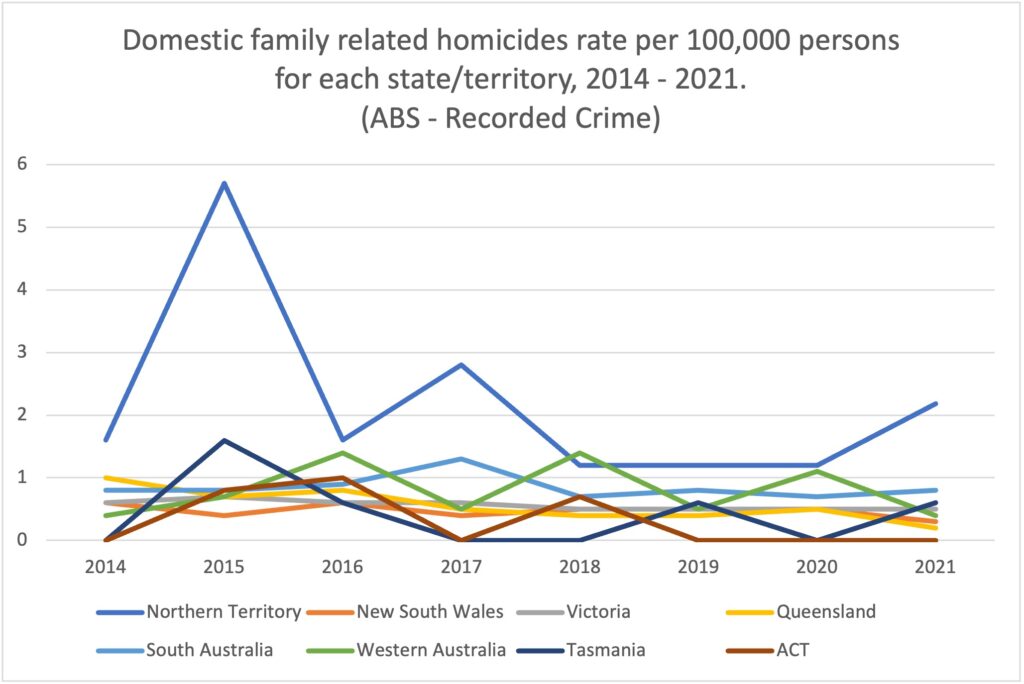

Domestic family violence is also disproportionately severe in the Northern Territory. Two of every five (41%) of domestic family violence-related assaults involved the use of a weapon, and the rate of domestic family violence-related homicide in the Northern Territory is 7x the national average. Responding to DFSV makes up approximately 80% of police work in the Northern Territory.

Figure 2 2021 Domestic family violence-related homicide per 100 000 persons

Domestic, family, and sexual violence also disproportionately impacts Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Between 2000-2021, Aboriginal women made up 70% of all intimate partner perpetrated assault deaths in the Northern Territory.

Figure 3 Domestic family violence-related homicides per 100 000 persons over time

Whilst rates of sexual assault in the Northern Territory remain unacceptably high, reports of sexual assault in the Northern Territory are falling comparative to other jurisdictions. As sexual violence cooccurs with intimate partner violence, this suggests significant underreporting of sexual violence in the Northern Territory.

Despite this high and severe rates of DFSV in the Northern Territory, recent reporting into missing and murdered First Nations women by Four Corners found that due to its small population, the Northern Territory receives just 1.8% of federal domestic, family, and sexual violence funding.

High Cost of Service Delivery

The Northern Territory has a diverse population spread across incredibly remote areas – many of which are regularly cut off or inaccessible for large parts of the year. This complicates service delivery and makes it more expensive, further reinforcing the need for needs-based funding.

The Northern Territory is not a state, and therefore does not have the same legislative or fiscal capabilities as other jurisdictions. It is more reliant on federal funding. But this funding is determined by population size.

The Northern Territory has a population of approximately 250 000, and approximately 130 000 of those live in Darwin, meaning that the Northern Territory’s population is spread across largely remote areas. The Northern Territory’s population density is approximately 0.18 persons per square kilometre. The remoteness of many communities in the Northern Territory significantly elevates the cost of service delivery.

Women in remote and regional communities are 24 times more likely to be hospitalised for domestic violence than women in major cities, and those from remote and regional communities encounter significant barriers to reporting and seeking help.

Many remote communities areas lack essential services, including shelters, meaning that victim-survivors often have to travel hundreds of kilometres to access a service. Some services offer outreach services, but these are expensive and funding-dependent. Many remote communities lack basic infrastructure including roads and phone network coverage, further complicating service delivery.

The diverse population of the Northern Territory, comprising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, migrant and other non-Indigenous communities, means that all work to address DFSV must be responsive to its population. Approximately 30% of the Northern Territory’s population is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, 76% of whom live in remote areas. More than 100 Indigenous languages are spoken fluently in the Northern Territory, plus languages spoken among those from refugee and migrant backgrounds. Language, cultural factors, and remoteness required tailored and contextually-specific response efforts.

Without needs-based funding, the inequalities that currently exist between regional and remote places and urban centres will be exacerbated. Further, without needs-based funding, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities will be further disadvantaged.

Members of the Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group undertaking a U Right Sis? workshop. Picture: Supplied

Lack of the presence by National Organisations

A number of domestic, family, and sexual violence peak organisations in Australia lack a strong presence in the Northern Territory. This is often due to lack of contextual knowledge and responsiveness to the Northern Territory’s needs and priorities, as well as few established connections and networks. For instance, national helplines are little use in much of the Northern Territory where there is no phone network coverage – and even if there was, it’s unlikely that services based in far-away cities could provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services to remote communities in the NT. Other organisations also lack culturally responsive messaging and resources, and are often inaccessible to people in the Northern Territory, especially for those of who speak English as an additional language.

Yet many of these organisations are funded at more than double the entire Northern Territory DFSV budget – and some are funded at ten times the entire Northern Territory DFSV budget. For instance, Our Watch received in excess of $100 million in federal funding in 2022.

The lack of meaningful partnerships with national organisations increases the complexity of addressing domestic, family, and sexual violence in the Northern Territory. It is incumbent upon these organisations to support the Northern Territory’s calls for needs-based funding.

What would needs-based funding mean?

The lack of support for needs-based funding from the Commonwealth government and other states might reside in a misunderstanding of what needs-based funding would mean for other jurisdictions. If DFSV funding is increased, the Northern Territory getting what it needs does not necessarily mean that other jurisdictions funding will decrease – the NT is not just asking for the pie to be cut up differently, it’s asking that we make the pie bigger.

This way, the Northern Territory can get what it needs to address the high and severe rates of DFSV here, whilst other jurisdictions also don’t miss out. Furthermore, needs-based funding could also provide the opportunity for other jurisdictions to look at how their funding is allocated and address existing inequalities within their own states. It requires a shift away from funding based on population, to getting funding to where it is needed most. Needs-based funding can benefit everyone.

It is painful to those of us who have lost loved ones to domestic, family, and sexual violence to see our government continue to ignore this crisis. Needs-based funding is a chance to do things differently – to make a stand and to fully commit to ending violence. Women and children’s lives matter. It’s time that our funding models value their lives.

Needs-based funding now.

- Picture at top: Galiwin’ku Women’s Space organised a fun run against family violence in Galiwin’ku. Photo: Supplied