The Whitlam government of 1972–75 transformed Australia. And yet the scope and scale of the reforms for Australian women are often overlooked. A new book called Women and Whitlam: Revisiting the revolution. BroadAgenda editor, Ginger Gorman, chatted to the book’s editor, Michelle Arrow.

Why was Gough Whitlam – as a political figure – so interested in women’s rights?

Whitlam was part of a group of Labor figures in the 1960s who wanted to reform the Labor party to focus on human rights, not just worker’s rights, and to think about other kinds of inequality other than class. This meant he was much more open to action on Indigenous rights, on poverty and disadvantage, and of course, on improving women’s rights.

Why did you personally want to revisit the Whitlam period, with this focus?

There were two reasons I wanted to revisit the Whitlam era. The first was that in 2019 I was lucky enough to be part of a conference organised by the Whitlam Institute called ‘Revisiting the Revolution’. The conference was the brainchild of the late, great Susan Ryan and Leanne Smith, then the director of the Whitlam Institute, and it was held in old Parliament House, a place filled with history and meaning.

To be there with all those women who had played such a crucial role in the social change of the 1970s was tremendously inspiring, and editing this book was my attempt to recreate the experience of being at that conference, and to amplify these women’s voices.

The second reason is that since that conference in 2019, the impact of COVID, the March for Justice, and the impact of the Morrison government, we saw a feminist reawakening in Australia. I felt that Australia’s trailblazing feminist history had something to say to that moment.

Among feminists, many of Whitlam’s achievements for women are well known. But can you summarise them for us? Why WAS this period so groundbreaking?

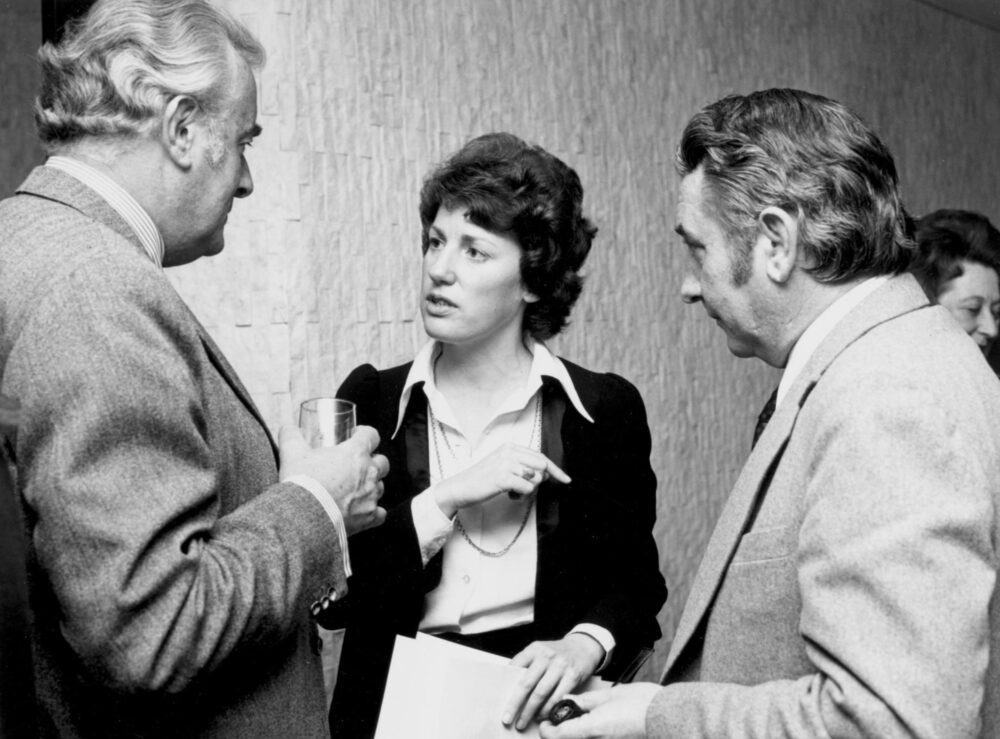

Michelle Arrow is a Professor of History at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. Picture: Supplied

The Whitlam era was a period of significant reform in many aspects of life, but the scale and scope of reforms for women were remarkable. A few of the most significant reforms were:

Expanded access to child care, equal pay for work of equal value, the introduction of the supporting mothers’ benefit, cheaper, more accessible contraception, government funding for women’s refuges and women’s health centres, no-fault divorce, free university education, which was of particular benefit to older women, and a grants program of more than $3m for groups around Australia to celebrate and commemorate International Women’s year in 1975.

Much of this was spearheaded by Whitlam’s women’s affairs adviser, Elizabeth Reid (pictured at top), who was appointed in April 1973. She was the first women’s affairs advisor to a national leader anywhere in the world! She helped develop women’s policy machinery to make government more responsive to women’s needs. This was truly groundbreaking. Whitlam recognised women as a distinctive political group whose needs were not always met by policy settings that focused on men.

Not long ago, I interviewed Elizabeth Reid regarding her role as women’s advisor to national government — a world first at the time. It was astounding to think of an Australia without women’s refuges or the single mother’s benefit and paid maternity leave. It showed me how far we HAVE actually come when it comes to women’s equality. How has this book made you reflect on this historical period?

One of the lessons from the Whitlam era that I think is most important is that some of these significant policy changes – like the introduction of government-funded women’s refuges – were the product of radical activists and reforming governments working together, or at least working in mutually productive ways.

Elsie Women’s Refuge, the first feminist-run women’s refuge in Australia, ran for nine months on volunteer labour and donations before it received its first injection of funding from the Whitlam government. What governments do is crucial. But what activists do – outside of government – is just as important for creating the conditions in which governments can make change.

The cover of “Women and Whitlam.” Published by NewSouth

One commentator suggested this book shows politics can be radical. How does this collection of essays reflect that?

I think it reflects it in a number of ways. The formation of the Women’s Electoral Lobby in 1972 was a radical move because it forced women’s political issues onto the national agenda in a way that they had never been there before, even though WEL was regarded as a reformist, rather than a revolutionary organisation. WEL interviewed every candidate running in the 1972 election and ranked them on their policy positions on women’s issues – the survey made a huge impact in the election campaign.

Second, it shows that Women’s Liberation was able to secure a seat at the table of the Prime Minister, to advise on government policy. Elizabeth Reid, Whitlam’s women’s affairs adviser, was a member of women’s liberation before she took the role. She was an activist and a tutor in Philosophy at ANU – not a professional bureaucrat – and she approached her role in a radical way.

She was just as concerned with changing the ways women thought about themselves as she was about providing better childcare.

This mixture of radicalism and pragmatism was a hallmark of the era, I think.

Third, Reid always spoke about how important it was to have allowed an active feminist movement outside government to shape decision-making inside government. There was a strong relationship between revolution and reform, and this book shows that.

What are the lasting impacts of the policy reforms of the early 70s?

There were two key impacts worth noting. The first was many of these reforms challenged the deeply ingrained idea that women’s sole, lifelong role was to be a wife and mother, dependent on a male breadwinner. The introduction of the supporting mothers benefit, which meant women could be mothers without marrying, or they could leave abusive partners. Funding women’s refuges gave women alternatives, as did the passage of the Family Law Act. Free higher education and equal pay (in theory, if not always in practice) meant that many women had a much firmer foundation for their independence, if they wanted it.

The second impact I think was Whitlam’s focus on women (and women’s increased political activism) established that women were a distinctive political constituency, especially for Labor. Over subsequent decades, we’ve seen working and middle class women shift more firmly into the Labor camp (when for much of the twentieth century many women were more likely to vote Liberal). In the most recent federal election, we have also seen that governments which ignore women, or fail to appeal to them, will pay an electoral price for that neglect.

What’s your favourite story or anecdote in this book? What’s something that really surprised you?

I think one of my favourite stories in the book is about the late Pat Eatock. Pat was an indigenous activist who played a very important role in establishing and maintaining the Aboriginal Embassy in 1972. She later stood for Parliament in the 1972 election for the Black Liberation Party – and Elizabeth Reid was her campaign manager.

Perhaps the detail of her story that I like the best was that Pat was the only candidate to achieve a perfect score on the Women’s Electoral Lobby survey – if only she’d been elected!

Some believe feminist progress has stalled since this era. How would you respond to that?

Sara Dowse (one of the book’s contributors) was asked this question recently, and her answer was really striking. She said that one of the things that made her feel that feminist progress had been made was that when she was a girl she was raised with a pretty narrow set of expectations for her life. Her granddaughters, however, had no such limits on their imagination or ambitions. And that was one of the goals of women’s liberation, to expand women’s horizons. I think we could regard that as a success.

However, there are still significant structural barriers in place for women. And we know those structural barriers are much more rigid for poor women, older women, CALD women and First Nations women.

We know rates of violence against women remain unacceptable, especially Indigenous women. But there has been a change in the ways that we discuss these issues publicly. In the 1960s. Domestic violence was not really discussed in public because it was not regarded as a public problem.

Feminism has transformed the ways we talk about violence against women and women’s rights but we don’t always have the best public policy responses. The new Labor government has taken some encouraging steps, especially on improving wages and conditions for female-dominated industries – again, as a result of years of feminist advocacy.

If we think about looking forward to the future, what do you hope readers take from Women and Whitlam?

This book pays tribute to the feminist activists of the 1970s, and I hope that it might introduce some of these women to a new generation. And by placing their essays alongside writing by younger feminists, I hope it can open up productive intergenerational conversations.

I also hope that the book shows us that there are many different ways to achieve reform, and that it a reminder that we need to use all the levers at our disposal if we’re going to make life better for all women – from radical protest to working with government. And most importantly, if you want a better world, you need to turn up and help make that change! These women are all fabulous role models for those who are trying to change our society, culture and politics for the better.

- Picture at top: Prime Minister Gough Whitlam discusses International Women’s Year with two members of the National Advisory Committee, Ms. Elizabeth Reid and the Secretary of the Australian Government’s Department of the Media, Mr. James Oswin. Source: National Library of Australia obj-137047143

Ginger Gorman is a fearless and multi award-winning social justice journalist and feminist. Ginger’s bestselling book, Troll Hunting,came out in 2019. Since then, she’s been in demand both nationally and globally as an expert on cyberhate and the real-life harm predator trolling can do. She's also the editor of BroadAgenda and gender editor at HerCanberra. Ginger hosts the popular "Seriously Social" podcast for the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. Follow her on Twitter.