Every year miscarriage affects up to 150,000 Australians and the people that love them. So why are we so damned bad at dealing with it? Journalist Isabelle Oderberg has written a groundbreaking book called Hard to Bear. The work investigates the science and silence of miscarriage. BroadAgenda editor, Ginger Gorman, had a chat with Isy about the book’s themes.

Tell us about your own personal backstory that led you to write “Hard to Bear”.

During our journey to complete our family, I experienced seven pregnancy losses. Obviously during that time I did a lot of reading in my quest to figure out why my body couldn’t do what I needed it to do. Being open about it publicly meant a lot of other people made disclosures to me about their own experiences. But I didn’t feel comfortable writing about it until our family was complete.

Once we decided that it was, I started reading again. And I realised that while I had some answers, I also had a lot of questions. And there was a huge amount of work and unpacking to be done in this space. And I thought there was no one better than me to do it, with the lived experience but also the ability to put that aside where necessary and wear my journalism hat to approach the issue with a forensic eye, while never losing sight of the human element.

There were so many OMG moments that just stopped me in my tracks. Like the moment I realised we had no idea how many people are actually having miscarriages in this country. Absolutely no idea.

You’ve long been vocal about the silence around miscarriage. Unpick this for us. Why the societal shame and silence? How does your book try to change this?

One thing that drives me crazy in this space is acknowledgement of the silence without understanding of why it exists and where it comes from. So that’s a big part of the book; unpacking it so we can move forward. We have a multitude of issues that feed this silence.

Miscarriage exists at the intersection of two things we find incredibly uncomfortable in Western society: grief and menstruation. Also it’s wrapped up in Judeo-Christian tradition, abortion and misogyny.

It certainly wasn’t always this way. I also do a lot of digging around other cultures that treat and talk about it completely differently. I really do find it fascinating.

Your book is also funny. Why does humour play a role here?

I’m Jewish and I draw on a long cultural tradition of irony, satire, self-deprecation and Black humour. There absolutely is a lot of humour in this book, where appropriate. I want people to enjoy reading it to whatever degree that’s possible, without struggling under the weight of a heavy topic. We can acknowledge the sadness of something while still finding ways to smile along the way.

Your book delves into the science (in addition to telling personal stories). Every year miscarriage affects up to 150,000 Australians and the people that love them. What do we know about why it happens and how it can be prevented?

I guess that’s a core part of the book: there is far too much we don’t know. And the things we do know aren’t properly explained to the people birthing the babies or their partners or families. For instance, environmental factors are a huge risk factor. But we don’t talk about it. Also, poverty. Nutrition.

And as in medicine so often, there are often factors overlaying each other that increase your risk profile. I do examine some of the factors that can contribute, both the commonly known ones and the ones we’re not talking about. But if there was more extensive testing and funding for research, we’d know far more.

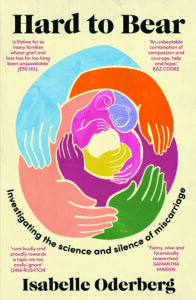

Hard to Bear: Investigating the science and silence of miscarriage (published in April 2023 by Ultimo Press.)

How does “medical misogyny” play into this?

We know through the work of journalists and authors like Gabrielle Jackson (Pride and Prejudice) and Kylie Maslen (Show Me Where It Hurts) that medical misogyny affects almost all aspects of medical care for women or people with uteruses.

This was acknowledged by the medical journal The Lancet when it wrote that the era of just telling women to try again after miscarriage is over. This issue affects up to 150,000 Australian families each year (and could be higher, we don’t know). We are decades past the time when we should have started talking about it openly.

Conversely, what do you have to say about the need medical kindness around instances of miscarriage?

The Australian medical system is not fit for purpose. It is stretched far too thin. And consecutive governments want to fix it with band-aids, if at all, rather than giving it an overhaul and structuring it from the presence.

Where there are medical and allied health practitioners who do want to do better (and there are many of them), often they are restricted by structural barriers. And the other thing I would say is that where medical practitioners do express kindness and compassion – I can tell you from the hundreds of patients I’ve spoken to – it is remembered and valued for the rest of our lives.

What role does hope have in this discourse?

This book is aimed at being fully accessible and fully inclusive. We are a village. We have to lift up parents whose journey to children isn’t easy and give them hope. Through sharing my story and doing this research, that’s what I want to do. Otherwise, I’m sharing for the sake of sharing and that’s just not my jam.

Equally, hope must be felt in our fight to change the system. Because otherwise what’s the point? This book is absolutely a book of hope that aims to improve the experiences of my children and theirs. We can do it. We absolutely can.

- Hard to Bear is out now.

Ginger Gorman is a fearless and multi award-winning social justice journalist and feminist. Ginger’s bestselling book, Troll Hunting,came out in 2019. Since then, she’s been in demand both nationally and globally as an expert on cyberhate and the real-life harm predator trolling can do. She's also the editor of BroadAgenda and gender editor at HerCanberra. Ginger hosts the popular "Seriously Social" podcast for the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. Follow her on Twitter.