Gender is a double-edged sword. It can aid the rise to political power for women but can also limit their political ambitions, including what they can achieve for fellow women.

The presence of women in politics is clearly on the rise in Australia. Women will make up 38 per cent of MPs in the House of Representatives while 57 per cent of the Federal Senate will be composed of women. A remarkable 19 women will be first-term MPs in the lower house.

What will the political and personal lives of these new women MPs be like? Will life be better in the era post former prime minister Julia Gillard’s 2012 ‘misogyny speech’?

What can we learn from the women leaders who have gone before them?

My research on the few women who have made it to the lofty heights of head of government – whether prime minister or president – may offer some answers.

The sex and gender of ‘Madam President’ has been a constant subject of political debate. In the rise of women to executive office, her sex is made overt, at times by the woman leader herself and often by those around her; gendered norms (re-emerge) in these debates and an evident battle ensues as to the relevance of a leader’s gender to national leadership.

Battling assumptions about their gender has been a relatively common experience for female presidents and prime ministers globally. From Thatcher in the United Kingdom to ‘Africa’s Iron Lady’ Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia. From Chile’s Bachelet to New Zealand’s Shipley, Clark and Ardern, not to mention experiences in our very own backyard.

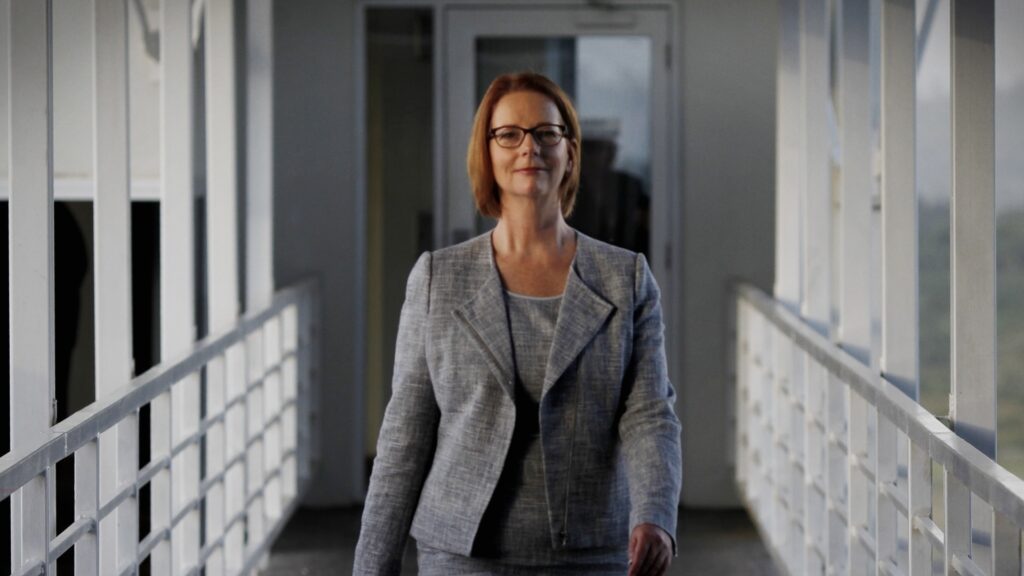

Former Prime Minister Julia Gillard in the documentary, Strong Female Lead. Picture: Supplied

While Gillard’s speech and the offensive characterisations of her as a female leader will be the subject of her new book, it would be wrong to assume that her experience was particularly unique.

Sri Lanka’s President Kumaratunga made constituents unhappy with her short hair and free will as an unmarried woman (in this case widow) in ways that trigger stark reminders of the media and public rebukes suffered by Gillard.

If these experiences, where women become political objects of discussion and not subjects of the political process, are anything to go by, the decisions of our new women MPs regarding marriage and motherhood and their appearance may too quickly and wrongly become the central focus of the media and in turn, public attention.

And yet we have seen how gender can aid a candidate’s rise to power. First, being a woman is a distinct trait that political campaigns use when there is a desire for change in the gender balance of politics. Liberian supporters were seen waving signs with, ‘Ellen, she’s our man’ at rallies, not perhaps a full shift in gendered expectations, but a shift.

Second, being a woman can help capture some segments of the vote. It was fairly evident how the female vote swung Australia’s federal election in May.

For women leaders as diverse as Chile’s Michelle Bachelet and the Philippines Corazon Aquino, a kind of hysteria (or ‘Corymania’) emerged as the ‘woman’s vote’ was mobilised in their favour.

Third, being a woman candidate can bring political capital based on assumptions that contesting women benefit from. Women are generally perceived as less corrupt – what has been described as ‘a myth in the making’ – so in Australian debates about a federal anticorruption commission, being a woman may add some legitimacy to the proposal.

Nonetheless few of the contenders in the recent election were explicit about a gender equality agenda. We might even wonder if prioritising gender equality explains, in part, the defeat of Jane Caro who ran for the Senate or Sheneli Dona, who ran for the house. I would like to think it gained them more votes than what was lost, but, perhaps that is not the reality.

Gender is indeed a double-edged sword.

What does this political reality mean for the women who made it? They have entered a political landscape where too few women have gone before and gender can be used as much for as against political success?

Will being ‘female’ stifle the potential for these women MPs to make a difference?

Can they still help ensure that the Albanese government will be able to generate the women-friendly legislative and policy outcomes that many of us are hoping for?

At this stage, it is probably safe to expect three things:

First, these women are role models and may better represent women’s issues. A greater diversity of Australian women can feel represented by parliament, with women from such distinct backgrounds as Sally Sitou, Zaneta Mascarenhas, Cassandra Fernando and Michelle Ananda-Rajah. I certainly feel better represented as an Australian woman of Asian origin. Not, as Sitou said, because of diversity for diversity’s sake but for what a diversity of parliamentarians can bring.

These women’s successes may also have the role model potential to inspire future generations of Australian women politicians. My research shows that the utterance of ‘She’ or ‘Madam’ means far more than a simple shift in gender pronoun.

Second, if the experience of other nations is anything to go by, women’s groups mobilise more resources and at a faster pace to exploit the window of opportunity that exists when women are in decision-making roles. We might see the kind of co-beneficial alliance building between women’s groups and women’s parliamentary bodies that we know this context gives rise to. And the outcome? Hopefully more women-friendly policies and across a much broader spectrum of issues – finance, the environment, corporate governance – because after all, all policies matter to women.

Finally, at the very least, the tone has been set right. Katy Gallagher, Australia’s new Minister for Women, has also been appointed Minister for Finance and Minister for Public Service. This is a far cry from the ‘feminine’ or low-prestige portfolios too often given to women cabinet members.

- The Woman President by Dr Ramona Vijeyarasa is out now.

Dr Ramona Vijeyarasa is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Law and the Juris Doctor Program Head at the University of Technology Sydney. She has been honoured for her pioneering work in artificial intelligence research by Women in AI. Ramona is the Chief Investigator behind the award-winning Gender Legislative Index, a tool designed to promote the enactment of legislation that works more effectively to improve women’s lives. She's the author of The Woman President: Leadership, law and legacy for women based one experiences from South and Southeast Asia.