In this analysis, Anna Hough of the Australian Parliamentary Library analyses the gender composition of Australian state and territory parliaments in comparison to that of the Federal parliament. This analysis was originally published on the Parliament of Australia website.

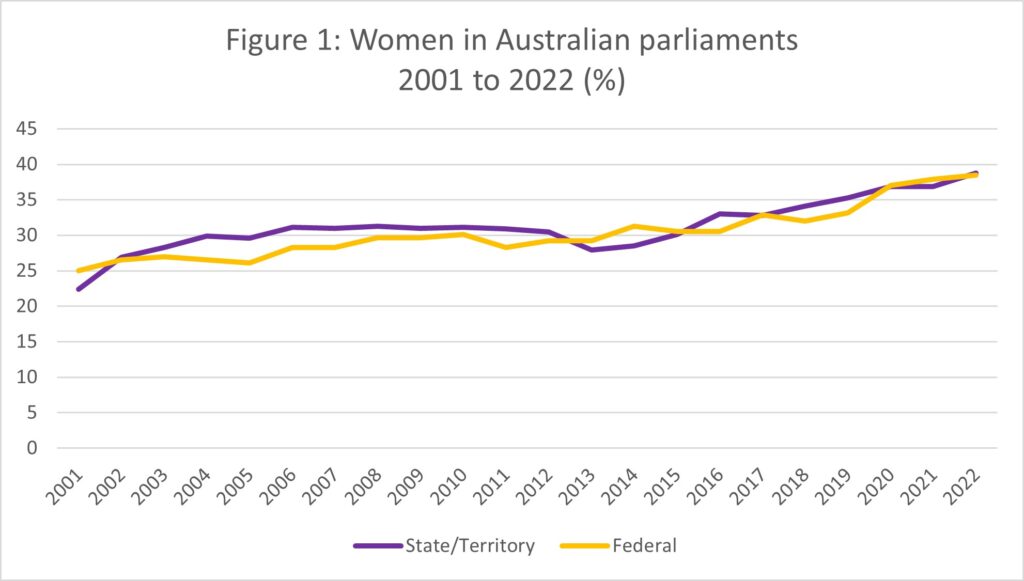

How does the gender composition of Australian state and territory parliaments compare with that of the federal parliament? As of 1 January 2022, 39% of federal parliamentarians and 39% of state and territory parliamentarians were women. Over the past two decades, the proportion of women across state and territory parliaments has tracked closely with the proportion of women in the federal parliament. Women’s overall representation in state and territory parliaments has increased from 22% in 2001.

Figure 1 below show women’s representation in the federal parliament, and in all state and territory parliaments. In the case of the federal parliament and the bicameral state parliaments, these are combined figures for both chambers.

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Gender Indicators, Australia’ and Parliamentary Library data. Reference point is 1 January each year. These figures are calculated according to the current number of parliamentarians, and do not include vacant seats.)

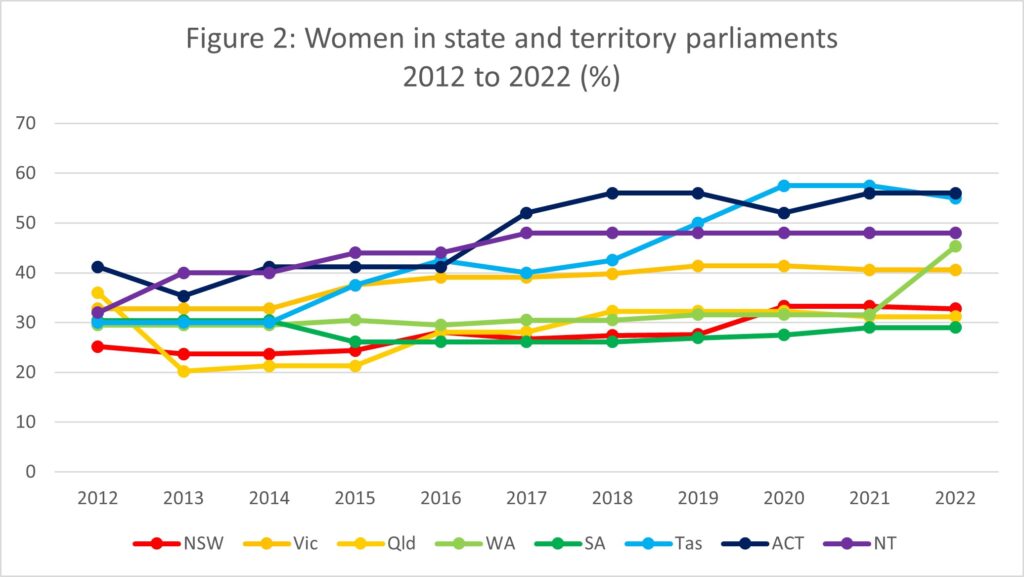

Figure 2 below shows how the proportion of women in each state and territory parliament has changed over the past decade.

(Source: Parliamentary Library historical data. Numbers as of 1 January for 2016–2022 and other dates in January and February for the other years. These figures are calculated according to the current number of parliamentarians, and do not include vacant seats.)

In 2016 the Australian Capital Territory’s (ACT) unicameral Legislative Assembly became the first Australian parliament with a female majority.

In 2018 Tasmania’s parliament followed suit, becoming the first state parliament with a female majority in the lower house, as well as the first state parliament to achieve equal gender representation across both houses.

The less populous Australian jurisdictions have led the way on gender equality among parliamentarians. To date the ACT and Tasmanian parliaments have been the only Australian parliaments to reach equal gender representation. The Northern Territory, with 48% women, is close behind.

Members of both the ACT parliament and the House of Assembly in Tasmania are elected using the Hare-Clark electoral system, a method of proportional representation where multiple members are elected for each electorate. (Tasmania’s Legislative Council is elected using preferential voting with single member electorates, in a similar manner to the federal House of Representatives.)

The electoral system used in each jurisdiction, and in each chamber of bicameral parliaments, is one factor that influences their gender composition. More women tend to be elected to parliaments, or to houses of parliament, via proportional representation than via preferential voting. For example, in Australia the Senate has a higher proportion of women than the House of Representatives. When it comes to Australian state and territory parliaments, however, the picture that emerges is more complex.

At the time of publication, this tendency holds true for the ACT Legislative Assembly, and the Victorian and the South Australian legislative councils (upper houses). In addition, Queensland’s unicameral parliament, which is elected via preferential voting, has a relatively low proportion of women.

However, the legislative assemblies (lower houses) of New South Wales and Western Australia, which are elected by preferential voting, have a higher proportion of women than the legislative councils of those states, which are elected by proportional representation.

The Tasmanian Legislative Council (upper house), which is elected by preferential voting, has a higher proportion of women than the Tasmanian House of Assembly (lower house), which is elected by proportional representation. And, as discussed above, the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly (single house), which is elected via preferential voting, comprises 48% women.

These differences suggest that, as well as electoral systems, other factors affecting the gender composition of parliaments and houses of parliament also play an important role. Those factors include each parliament’s party composition, as well as party and voter choices about candidate selection and election.

There is evidence, including from Australia and from the European parliament, that parliaments dominated by progressive parties are likely to have higher female representation, as more women tend to be preselected as candidates, and to be elected in parties from the progressive end of the political spectrum. Gender quotas, whether legislated by countries or introduced voluntarily by individual parties, play a critical role in increasing the proportion of women in parliament.

Women, including independent candidates running in what had previously been considered safe seats, made gains at the federal election on 21 May 2022. However, evidence from the Australian parliament, and from comparable parliaments such as that of the United Kingdom, indicates that it is not sufficient to simply increase the number of women running for office.

To substantially improve women’s representation, women need to be preselected for winnable seats, rather than for ‘glass cliff’ seats that they are less likely to win. While recent research by the group Women for Election Australia suggests that the majority of Australians would like to see more women in politics, and other research indicates that voters have generally positive views of female candidates, gender is also perceived as a key barrier to women’s electoral success.

Further reading

- Anna Hough, Janet Wilson and David Black, ‘Women parliamentarians in Australia 1921-2020’, Research paper series, 2020-21, (Canberra, Parliamentary Library, updated 9 December 2020).

- Anna Hough, ‘Women in parliament and politics: a quick guide to key internet links’, Research paper series, 2020-21, (Canberra, Parliamentary Library, 15 December 2020).

- Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, ‘Election 22 — Glass cliff candidates’.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union, ‘Women in Parliament in 2021’.

- Please note feature image is a stock photo. It shows voters in the 2019 Federal election in Sydney. Source: Shutterstock/MW Hunt

Anna Hough is a researcher at the Australian Parliamentary Library. Her research focuses on political and public administration issues, particularly those relating to women in politics.