Over summer, BroadAgenda is republishing some of its most popular articles. This compelling piece was first posted earlier this year.

Picture this: a young mother, struggling across the road with a cumbersome contraption that appears to be two cheap strollers screwed together. A pair of male police officers watch her, amused. They don’t offer to help her over the curb, instead making mocking comments about her: Serves you right. She is 21, but looks younger, and has two kids under the age of two in those strollers.

That young woman was me. Growing up as a 10-pound Pom in the low-socioeconomic status northern suburbs of Adelaide, I’d moved out of home at 15 and married at 18. There were certain expectations or assumptions about me that were reinforced by people in authority, like these two police officers. These limiting assumptions – being a teenage mum, being poor, being female – also stood in the way of one of my daughters receiving appropriate medical treatment when she suffered an aneurism at eight months old.

When we presented at hospital and the medical staff noticed a small bruise on her arm, the immediate assumption was one of child abuse. When I tried to explain that the was the result of a recent vaccination, they didn’t believe me.

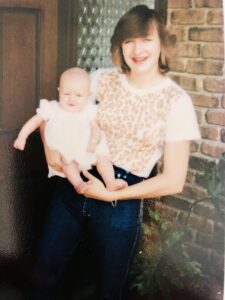

Niki, age 19, with daughter Kyla. Picture: Supplied

When I tried to explain the symptoms and that my baby who could usually crawl was now unable to sit up, they ignored me. As a young woman, I had become used to people not taking me seriously but never in a situation like this.

How could these medical professionals, people who were charged with caring for my daughter, refuse to consider information from the child’s parent?

Would they have treated me the same way if I was older? If I was wearing more expensive clothing? Or if I was a man? It was when I became a parent that I realised how unequal the world was, and this experience reinforced it. It took days – and finally a neurosurgeon – before the medical team could see past their bias and listen to me. I have never felt so powerless and frightened.

These two incidents are not the only time I’ve experienced discrimination based on my gender, age, or socioeconomic status, but they illustrate how these factors intersect. Academic Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” to describe how multiple aspects of discrimination and disadvantage stack up. Identity characteristics do not exist independently but intersect to create complex forms of oppression, inequality, and exclusion. For example, recent figures show that Aboriginal people, LGBTIQ+ people, young women, people with disability and those on lower incomes are much more likely to experience workplace sexual harassment.

Niki’s PhD graduation and second university medal age 51. Picture: Supplied

My own experiences of discrimination and sexual harassment were compounded – and it didn’t help that my husband had an affair that led to our marriage breakdown.

As a single mother of four young children, you can imagine the kinds of assumptions people made about me. I could easily have become disengaged from my education and career possibilities, facing an impossible juggle with caring responsibilities, but a positive workplace experience changed it.

By now, I’d completed a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Psychology. I’d been getting straight distinctions, but because I was caring for my children and working part-time to run the family building company, rather than spending time with other students, I didn’t realise this wasn’t the norm.

I carried all those limiting assumptions with me – just like the police officers and medical staff – I looked down on myself. It was not until a notice arrived in the mail informing me I was to receive the University Medal for my academic performance that I realised I was smart, and probably had important contributions to make to the world (in addition to trying to be a good parent). This recognition changed my outlook completely and I gained the confidence to apply for a role in an academic centre.

By chance, another student overheard me talking to a university librarian about the job and approached me to say she was also considering applying but couldn’t take it on full time as she was still studying. Even though we’d only just met, we decided to apply together, and the lead professor agreed to a job share, which was very innovative in the mid-90s (my job-share partner and I are still close friends to this day).

I felt supported at work, but caring for my children, going through a marriage break up and being promoted to work on a challenging research project involving illegal drug users began to stack up. My boss recognised this and said: “I don’t care when or how you work, as long as you keep meeting the deliverables.”

The flexible working arrangements meant I could work around school drop-off and pick-up times, work from home if I had a sick kid or after hours when the kids were asleep. Not only did this flexibility help me succeed at work, it also set up my approach for how I would lead my organisations in the future.

I went on to establish the Leaders Institute of South Australia and run the Governor’s Leadership Program, where I noticed a lack of diversity among participants. Where were the women, the people of colour and those with a disability?

Niki with granddaughter Imogen. Picture: Supplied

Too often when people talk about diversity in leadership, they take a binary approach, simply replacing white men with white women, and failing to apply an intersectional lens. Tu Le and Molina Asthana recently wrote about the ‘double-glazed glass ceiling’ they face as women of colour. As an experienced board director, Molina has described her efforts to increase diversity only to be told that the mandate is for gender equality only – which can further marginalise women of colour and mean they are overlooked for leadership roles.

We needed to bring more diversity into the Governor’s Leadership Program, so I set up scholarships for women, people with disability and Aboriginal leaders – as well as leaders from rural and regional areas.

It was through this work in SA that I came to know and admire the work of the Equal Opportunity Commissioner for South Australia. When the job was advertised, I thought: why not? It was an opportunity to continue the work I had started, channeling my passion for equality that began when I was a young mother, struggling to be heard. That role then led me here to Melbourne as Victoria’s – and Australia’s – first gender equality commissioner, where I continue to draw on my own experiences and those I saw around me.

My family now includes 18- and 21-year-old stepchildren and a foster daughter (now 18, but who has been part of my family since she was 13). I also recently welcomed my 10th grandchild (remember, I had my kids young!).

Too many new parents still don’t have access to the workplace flexibility I had 25 years ago.

Niki with daughter Tami and granddaughter’s Charlotte and Poppy. Picture: Supplied

Consequently – as we’ve seen during COVID – outdated gender norms around parenting are re-enforced when women step back from work to care for their children because the juggle of working, home schooling and everything in between has largely been women’s burden to bear.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

As parents know (but employers seem to routinely forget) kids don’t operate on a timesheet. I’m heartened by organisations making changes to break down gender stereotypes around parenting. For example, South East Water has removed the definition between primary and secondary carer, allowing all parents access to flexible parental leave. For one new father, that allowed him to change his part-time working hours to accommodate his child’s challenging sleep schedule – and ensure both he and his partner got their own sleep in. Bass Coast Council has also made this change, as well as paying super on parental leave and making it the default for parents to work flexibly or part time.

I hope to see more organisations following this lead and breaking down these tired gender stereotypes and assumptions that can limit people in life.

I’m a product of what can be achieved when we remove bias, offer flexibility, and empower employees.

But we still have so far to go to make this a mainstream experience – and we can’t sit back and wait for this to happen. In fact, based on the current pace of change the World Economic Forum estimates it will take another 135.6 years to achieve global gender equality.

But not if my team and I have anything to do with it!

Dr Niki Vincent has a wealth of experience in gender equality and organisational leadership. As Victoria’s inaugural Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner, Dr Vincent is responsible for overseeing implementation of the Gender Equality Act 2020 and plays a key leadership role in promoting gender equality in the Victorian community and workplaces.