February 27 2024 could be a turning point for gender equality in Australia. That’s the day the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) will publish gender pay gaps for Australian private sector employers with 100 or more employees. For the first time, large organisations will have their gender pay gap data exposed, allowing stakeholders to take action.

In 2023, WGEA reported that the average total remuneration gender pay gap was 21.7%. This means that women in Australia are earning, on average, $26,393 less than men a year. But pay gaps vary tremendously across states, sectors and employers.

Pay gaps emerge at the very start of people’s careers. Researchers have documented small but consistent pay gaps between men and women graduating from the same university programs in the same year. Those gaps widen over time, as employers administer pay rises as a percentage of an employee’s current salary.

The gaps widen further when women take extended career breaks to accommodate family responsibilities. And finally, women retire with a superannuation nest egg that’s only about two thirds the size of men’s.

More transparency in pay gaps is a great first step, but its impact will depend on stakeholder pressure, and how organisations respond to it.

Are stakeholders ready to step up?

Thanks to WGEA’s impending publication of gender pay gaps, stakeholders won’t have to ask employers about the size of their gaps. But it remains to be seen whether the stakeholder-on-the-street will care. The complexity of causal factors driving gender pay gaps makes it difficult to generate a sense of moral outrage among public observers.

People usually agree that men and women should get the same pay for doing the same job, but when they learn that women’s lower pay is in part a result of being in low pay occupations or taking time out for their caring responsibilities, they see pay gaps as resulting from women’s choices – and are less likely to hold employers accountable.

Researchers have documented the public’s lack of concern in the UK, where employers have been publicly reporting pay gap data since 2018. Employers reporting narrow pay gaps enjoy a reputational boost in their Glassdoor reviews, but the boost is short-lived, lasting only a month. Even more discouraging, employers reporting pay gaps – even very large pay gaps – experience no reputational damage. Unless stakeholders show employers that they care about pay gaps, and that their pay gaps influence stakeholder behaviour, employers are unlikely to make the changes needed to narrow pay gaps.

And pay gaps that are published once a year are easily forgotten. In an effort to keep pay gaps on the public’s mind, a UK team developed a clever bot. Every time a UK company tweets about their International Women’s Day activities, the bot re-tweets it with the company’s gender pay gap information (along with data about whether the gap is widening or narrowing relative to the previous year).

What actions will organisations take?

In Australia’s history, we’ve seen that stakeholder pressures can have unintended consequences. From 2010, when the ASX Corporate Governance Council started requiring ASX-listed entities to report the gender composition of their boards and executive teams, we saw a huge spike in female appointments to senior roles. Our own research demonstrates the trickle-down effect of these senior appointments. But we also documented a gender pay gap at the executive level. That’s bad news for female executives, but it’s also bad news for their employers.

When firms had pay gaps in their executive teams, they experienced lower financial performance as they appointed more women into executive positions. Pay is an important signal about an employee’s value, and when firms pay female executives less than male executives, they create two-tier executive teams that fail to leverage the team’s diversity.

Elsewhere in the world, we’ve seen similar unintended consequences of gender pay gap transparency. Since 2006, firms in Denmark are required to make pay information available on request to relevant parties (e.g., unions). This legislative change has narrowed the gender pay gap but employers responded by compressing salary distributions. Women weren’t getting paid more, men were being paid less. That’s a risky move because pay is an important motivator of employee performance. A smart employer will close pay gaps by allocating separate funds to that purpose, rather than drawing funds from its rewards budget.

Professor Carol T. Kulik notes: “When firms had pay gaps in their executive teams, they experienced lower financial performance as they appointed more women into executive positions.” Picture is a stock image.

Where do we go from here?

More transparency in pay gaps is a good start, but it’s only the first step toward closing the gaps. There is a window of opportunity for well-organised bodies (policymakers, professional organisations, trade unions, the Australian Institute of Company Directors) to leverage public pay gap information to generate positive change. These bodies are best positioned to recognize the complexity of gender pay gaps, and help employers address the root causes.

At the same time, any stakeholder (employee, job applicant, consumer) can start asking employers better, and more informed, questions:

- In what roles and at what levels are your pay gaps most prevalent?

- How are you supporting employees’ caring responsibilities?

- What are you doing to ensure women move into roles where they are paid more?

- How long will it take you to close your pay gap?

Once these questions are routinised, we might finally start to see some progress toward closing gender pay gaps.

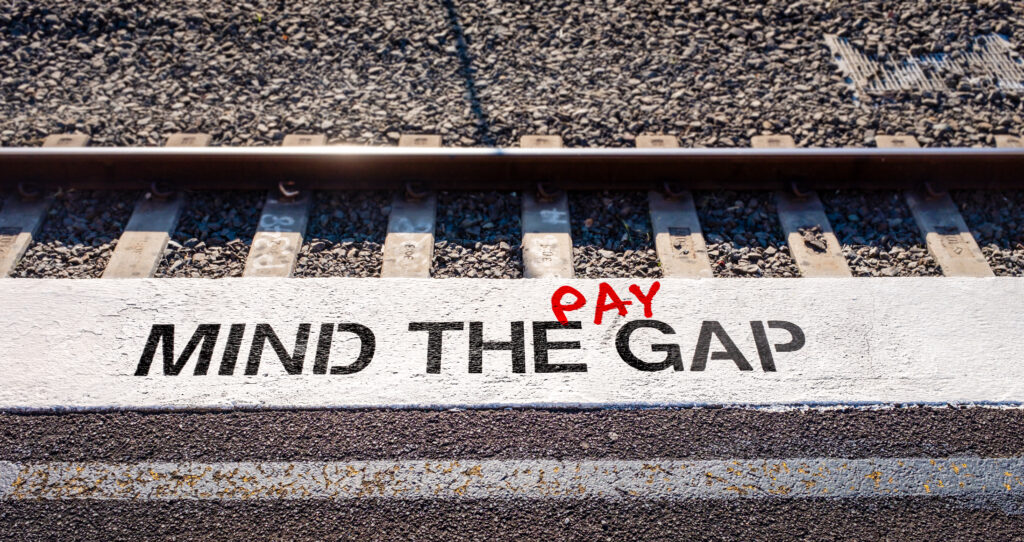

- Please note: picture at top is a stock image

Carol T. Kulik is a Bradley Distinguished Professor at the University of South Australia, UniSA Business, Centre for Workplace Excellence. She is the co-author of Human Resources for the Non-HR Manager (2023, Routledge), a book that makes the latest research on people management accessible to managers with no formal training in human resources.