Distinguished Professor Susan Scott, a theoretical physicist from The Australian National University (ANU) whose pioneering work has fundamentally altered our understanding of the deepest and darkest parts of the Universe and space-time itself has been recognised among the world’s best gravitational scientists. To find out more, BroadAgenda editor, Ginger Gorman, had a chat with Susan.

Congratulations on your astounding achievement – being elected as a Fellow of the International Society on General Relativity and Gravitation (ISGRG) for 2022! Firstly, if you were sitting next to a lay person at a dinner party and you were explaining the work you do in a nutshell, what would you say?

My research work is all about gravity and how it shapes the Universe.

I am an expert in Albert Einstein’s 1915 theory of general relativity which governs how gravity works.

The theory predicts the existence of gravitational waves, which are tiny ripples in the fabric of space-time caused by cataclysmic events in the Universe. I was part of the international team that directly detected gravitational waves for the first time in 2015, from two black holes colliding 1.3 billion years ago.

I know you have done crucial research on black holes. What are they and what do they tell us?

When a big star burns up all its nuclear fuel, it starts to collapse in on itself. It keeps on collapsing until an event horizon is formed – an event horizon is a boundary, like the surface of a ball, from which nothing can ever escape, not even light. That’s why these mysterious objects are called “black” holes.

They are another prediction of Einstein’s theory, and we now know that our Universe is full of them. They are the end-product of the life cycle of many stars, and they also collide with each other to form bigger black holes.

You have been appointed for your “groundbreaking contributions to the understanding of the singularities and the structure of space-time.” What are singularities? How do they impact our understanding of space-time?

Singularities are places in space-time where the physics goes badly wrong. For example, when a big star collapses to form a black hole, the finite mass coming from the star appears to be squeezed into a single point of space-time.

That means there would be infinite density at that point, and so it’s deemed to be a singularity! It is a major quest, going forward, to understand under what conditions in the Universe these singularities will form. We will also need a new theory, quantum gravity, to fully describe the nature of singularities, and what happens at the heart of black holes.

If we zoom out a bit, why is it important for mere mortals to understand the deep, dark parts of the universe (that we might not even be able to see)?

Gravitational waves will help us to probe parts of the Universe that simply cannot be observed by other means, such as with light and radio waves. As mere mortals, we live on a small speck (planet) in an unimaginably immense Universe, and we are driven to know what lies out there.

That’s why we are sending humans back to the Moon, and possibly on to Mars, and why we send out missions and telescopes into space. Now that we have the ability to detect gravitational waves, we have opened a new window onto the Universe which is unlocking many of its secrets.

You are the first Australian to be appointed to ISGRG. What does that mean to you?

It is a great honour to be the first Australian elected a Fellow of the Society, and I must say, a delightful surprise! The Fellowship is an elite group of only about 50 top gravitational scientists around the world, including eminent researchers such as Stephen Hawking, and Nobel Laureates Roger Penrose and Kip Thorne. It really is a wonderful recognition of my research work in this field throughout my career. I also think it is an indicator of the maturity, quality and depth that research in gravity in this country has now attained.

I note that Fellows of ISGRG are largely (but not entirely) men – including the likes of world renowned theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and Nobel Laureates Roger Penrose and Kip Thorne. Physics is still a male-dominated field. What kind of barriers have you faced as a woman in physics? Are those barriers still there for women coming up through the ranks today?

Physics has indeed been a male dominated field throughout my career. During the four years of my undergraduate degree, all of my lecturers were men. I think that, as a young woman, it is a real hurdle to progressing in a field like physics, when you cannot see any female role models.

The presence of female lecturers gives you the subconscious belief that you can succeed in such a field.

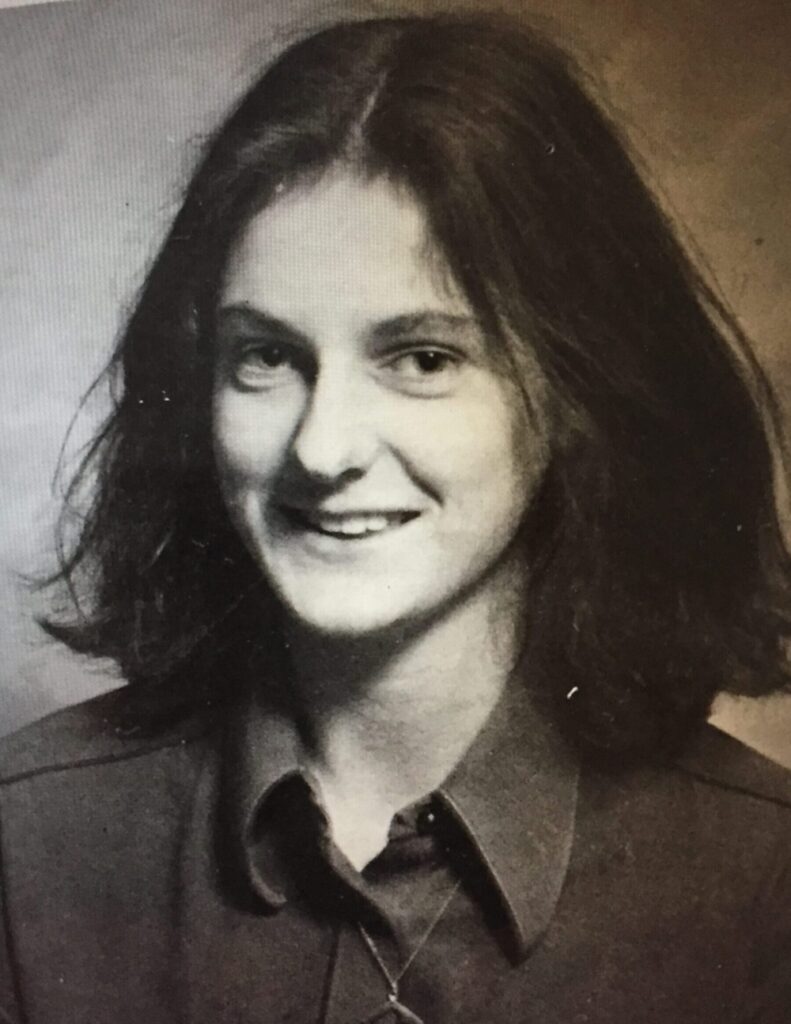

Susan in her final year of MLC when she became dux of the College, before she went to Monash University. Picture: Supplied.

I was the first woman to become a Professor of Physics (with another woman) at The ANU, and the first female physicist to be awarded the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science. These glass ceilings have been very hard to break, but once they are down, women who follow know that there is a tangible way ahead.

The presence of female lecturers gives you the subconscious belief that you can succeed in such a field. I was the first woman to become a Professor of Physics (with another woman) at The ANU, and the first female physicist to be awarded the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science.

These glass ceilings have been very hard to break, but once they are down, women who follow know that there is a tangible way ahead.

I lead the Professional Development program for the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav). We run a mentoring program for our members, as well as other professional development activities, and it is foremost in our approach that young women do need specially targetted programs to prepare and encourage them to continue with a career in physics.

If you go back to your own childhood, do you remember being interested in physics and science more generally? What led you here?

I recall that my favourite subject when I was at primary school was mathematics. I loved the purity, logic, precision and abstract nature of maths, and I slowly began to realise that I had a special talent for it.

A really important event also happened during that time, namely, there was the first landing on the Moon. We got sent home from school so that we could watch it on the television. I went to a friend’s house with a few other kids. They watched it for a short while, but quickly became bored with the murky transmission, and went outside to play.

I sat there glued to the screen for hours, and I remember being fascinated by the astronauts leaping about on the lunar surface. I believe that this historic event sparked my lifelong fascination with gravity.

Susan believes watching the moon landing in 1969 gave her a lifelong passion for gravity and how it works.

At that early time, I never imagined, in my wildest dreams, that it would be possible for me to develop a career involving mathematics and gravity. I was fortunate to win a scholarship to go to the Methodist Ladies’ College in Melbourne for my secondary education, which is a girls only school, and during those years my interest and aptitude for mathematics and physics was nurtured, and flourished.

While a number of my friends chose to go on to university to study medicine, I took the more unusual path, and decided to go to Monash University to do a Bachelor of Science degree specialising in mathematics and physics. By this time, I was simply following my heart, and heading off into the unknown, having no idea where it would all lead.

What is the next frontier of gravitational wave astronomy?

Since our first detection of gravitational waves in 2015, most of our more than 90 detections, including the first one, came from two black holes spiralling around each other, and then smashing together. When this happens, we detect a short burst of gravitational waves. The next frontier which we want to open in gravitational wave astronomy, is to detect the continuous gravitational wave stream coming from spinning, misshapen neutron stars.

These stars are made of the densest material known in the Universe. They can have up to a couple of times the mass of the Sun packed into an object about the size of Canberra. The properties of neutron stars, and the nature of their incredibly dense material, are great mysteries to us. The detection of their gravitational waves will help us to unlock the secrets of these very enigmatic objects.

Is there anything else you want to say?

It is so important that we encourage young women into STEM disciplines and STEM careers. Not only are there so many amazing, fascinating careers to be had in science, which women can certainly successfully pursue, the fact is, that to ensure the future health and survival of our planet, we simply cannot afford to miss out on half of our talent pool!

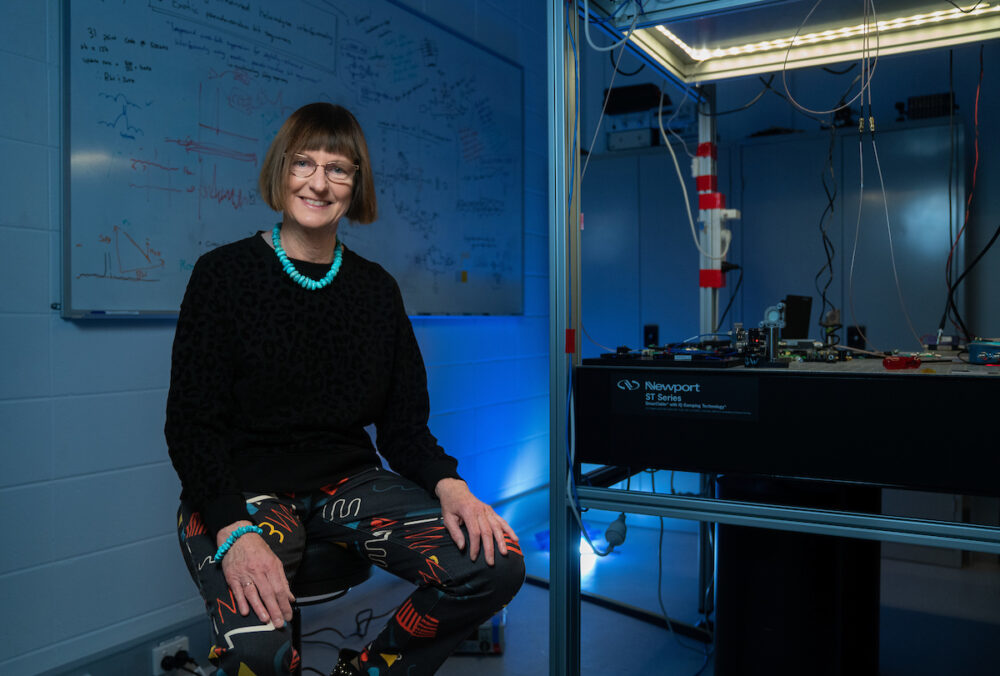

- Feature image at top: Distinguished Professor Susan Scott poses for photographs at ANU in Canberra, Australian, ACT, 11 July, 2022. (Tracey Nearmy/ANU)

Ginger Gorman is a fearless and multi award-winning social justice journalist and feminist. Ginger’s bestselling book, Troll Hunting,came out in 2019. Since then, she’s been in demand both nationally and globally as an expert on cyberhate and the real-life harm predator trolling can do. She's also the editor of BroadAgenda and gender editor at HerCanberra. Ginger hosts the popular "Seriously Social" podcast for the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. Follow her on Twitter.