In Old Parliament House, Canberra, (now the Museum of Australian Democracy), there’s an exhibition called Australian Women Changemakers. Along with the new crop of brilliant young changemakers such as Grace Tame, Kenyan-Australian refugee advocate, Nyadol Nyuon, and First Nations activist, Megan Davis, the exhibition also acknowledges the contributions of Australia’s second-wave feminists of the 1960s to 1980s – women like Anne Summers, Quentin Bryce and Elizabeth Reid.

Recently, Ginger Gorman, host of the Australian Academy of Social Sciences “Seriously Social” podcast, took Elizabeth Reid back to Old Parliament House to mark two “golden anniversaries”; 50 years since the election of Gough Whitlam in 1972, and the podcast’s 50th episode.

In 1973, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam appointed Reid as the world’s first advisor on women’s affairs to a head of government. This was remarkable at a time when not a single member of Australia’s 125 seat parliament was female.

There may have been no female MPs in 1973, but Reid had an ally on the inside. Her old school friend, Caroline Summerhayes, was Whitlam’s secretary. Summerhayes provided barometric readings of Whitlam’s moods; predicting whether the reception to Reid’s feminist advice was likely to be fine or stormy.

“Oh stay away. He’s in a foul mood!” Summerhayes would warn, or, “Yes, slip in. He’s in a good mood.” It is such small, but important, intel that greases the wheels of bureaucracy.

Born, the daughter of active trade-unionists and advocates for educational reforms, Elizabeth Reid was an academic and part of the Women’s Liberation Movement when Whitlam first advertised for an advisor on women’s affairs.

“I think it’s important to realise that we hadn’t ever been on the inside,” she says.

“Of course there were women in bureaucracies, but they hadn’t gone into bureaucracies to bring about changes for women … [whereas] we set out to end patriarchy, to destroy sexism.”

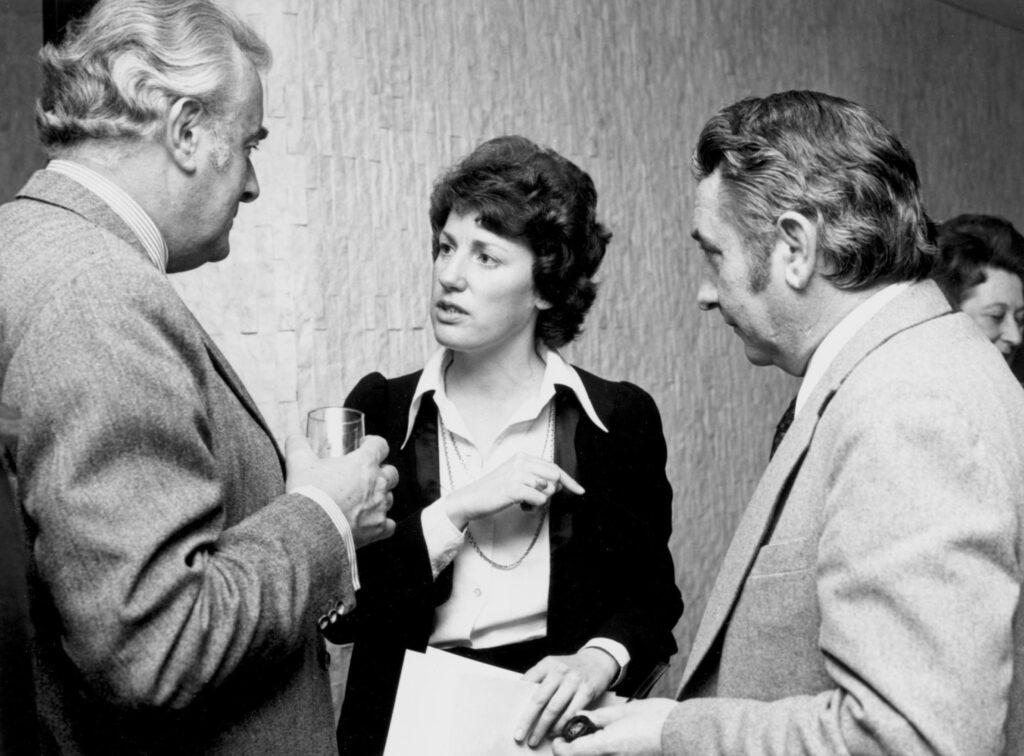

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam discusses International Women’s Year with two members of the National Advisory Committee, Ms. Elizabeth Reid and the Secretary of the Australian Government’s Department of the Media, Mr. James Oswin. Source: National Library of Australia, nla.obj-137047143, courtesy Australian Information Service.

During the 70s, these kinds of feminist/bureaucrats became known as “femocrats”.

Ironically, within the Women’s Liberation Movement, there was a great deal of resistance to the idea of feminists working within the system. Women’s Liberation was a revolutionary movement and, to many, working within a patriarchal system was tantamount to sleeping with the enemy.

But, Reid reflects, “I felt it was a challenge to the Women’s Movement … Never in recorded history had a head of government said, ‘Well, come on. Come in. Tell us what needs to be done.’”

“In effect, when Whitlam offered to open the halls of power to the Women’s Liberation Movement, he called our bluff.”

Despite photos from the time showing a young Elizabeth Reid surrounded by white men in suits, she says it never occurred to her that she wouldn’t succeed. But she soon found “you have to be savvy” to work the halls of power.

And, while still facing staunch resistance from within organised feminism, Reid’s mission was bolstered by a tsunami of correspondence from ordinary Australian women who felt, at last, there was someone in Parliament who might hear their voices.

“It was as if a wellspring opened up,” she says. “Many of these women would say, “I’ve been writing for years and nobody has done anything about it. But at last I feel there’s somebody there who can do something.”

Reid responded to concerns that a single individual could not adequately represent the diversity of Australian women by spending the first year of her appointment travelling the country and listening to as many diverse female voices as possible. This, combined with the influx of correspondence, gave her a sense of the issues “that were really gnawing away at women’s spirit and souls.”

In Reid’s view, the “reform vs revolution” debate set up a false dichotomy; her aim was to work within the system to achieve reforms, while instilling a “revolutionary consciousness” at the heart of Australian democracy.

At that time, single women were refused bank loans or mortgages without a male guarantor. Married women, temporarily unemployed, weren’t eligible for unemployment benefits. Widows received five-eights of the pension while widowers received full pensions. Women returning to Australia from overseas with their husbands, were not permitted to fill in their own quarantine and customs declaration. But always, at the forefront of Reid’s activism, was the recognition that the multifarious barriers faced by women sprang from a patriarchal system and culture.

She says, “My focus was on getting Whitlam to understand what changes we wanted, and to understand that no single change was ever going to be sufficient.”

A key achievement during Reid’s tenure was the introduction of maternity leave to the Commonwealth Public Service. But, she singles out the establishment of the Royal Commission on Human Relationships (1974-1978) as the culmination of the “revolutionary consciousness” that she, and other feminists, determined was vital to driving structural and cultural change.

Watch the full interview on Youtube.

“That was a groundbreaking and controversial commission,” Reid recalls. “It helped change public discussion around families, gender, sexuality and how marriage impacted a woman’s role in society.”

Despite these successes, strident opposition, not only from anti-feminists, but from within her own movement, took a toll on Reid. After she resigned from her government position, she went abroad to work with women in developing countries and didn’t return to Australia until the 2000s – when at least some of the hatchets were buried.

Revisiting her old workplace with Ginger Gorman, Reid reflects upon a time when Australian democracy was at its zenith: when there was a genuine commitment to structural change; when cross-party friendships and co-operation were commonplace, and; when Australians (even minorities) felt their voices were being heard by their political leaders.

Standing near the desk from which sixteen former prime ministers ran the country, Reid says, “In Australia, over the past couple of decades, I think we’ve been backsliding in our democratic traditions. I think this – this building – is a very good reminder that we once had sets of values that are very different from those we’ve been living with in recent years.”

Elizabeth Reid will be delivering the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia’s Cunningham Lecture on Tuesday 29 November at their Democracy Symposium. Reid’s will speech will be: “Protests and Democracy, Now and Then”?

Picture at top: Elizabeth sits in Canberra’s Old Parliament House in Whitlam’s former office. Photo: Ginger Gorman