Nothing to Hide is Australia’s first mainstream anthology of trans and gender diverse writing. In this excerpt, Stacey Stokes writes about her tough and painful journey to become a woman. This excerpt is published with full permission.

Content notification: This post discusses sexual violence, stigmatisation and discrimination based on a person’s gender identity.

When I was three years old, I started wearing my sister’s old dresses. They seemed so pretty to me. My favourite was the colour of a Cherry Ripe wrapper. The soft satin felt nice on my skin, and I loved the way it swirled around my legs. My parents must’ve told me that I wasn’t allowed to wear dresses because I hid them in a box deep inside an unused wardrobe, and wore them only when I thought I was alone.

One night, I went to my hidey spot and discovered that all my pretty dresses were gone. Who had taken them? Did they know that I’d put them there? I didn’t know. I was devastated, and afraid that I’d be told off by my dad at any moment for my secret, lost collection.

After all my pretty clothes had been taken away, I had to find new forms of beauty. Like fire. I loved the way that I could make it appear whenever I wanted and watch it dance around in its beautiful red colours.

When I was four, I set fire to the lounge room by inserting rolled up paper into the pilot light of the wall heater, then using the lit paper to make little fires on the carpet. My parents asked me if I had set the fire, but I shook my head. Then they asked who did it. ‘A little boy with brown hair, a Transformers Tshirt and grey pants,’ I replied. That’s what I was wearing, of course, but I was no little boy.

When I started primary school, I’d choose to play the princess in make believe games with the boys. It didn’t make me popular. I liked playing with the girls, but soon they began to exclude me too. I started to hate school, and did everything I could to avoid it.

One school day, I told my mum that I was sick, and I stayed at home alone watching daytime television. Mum was doing the washing, dad was at work and my brother and sister had gone to school, so I had the run of the house.

I sat crosslegged in the lounge room with the sun streaming in, watching our old boxy TV that looked like it had been sitting there since the Cold War era. TV was my window into the real world. At 12 o’clock, Jerry Springer came on. It was an episode about transgender people, and the audience cruelly pointed and laughed at all the guests. It hurt me terribly to see them being laughed at.

At the end of the show, Jerry talked about being transgender. He said, ‘If you want to be a girl, then you can be a girl. All you have to do is want it enough.’ So every night before I went to sleep, I concentrated as hard as I could on my dream of being a girl. But every morning, I woke up to find that I still had a penis.

My penis was so embarrassing to me. It was a dark and horrible shame that I didn’t want anyone to know about. When I dressed in trousers to go to school, I’d tuck it back and pretend it didn’t exist. I’d never, ever wear shorts, even in summer, because I couldn’t stand the sight of my little bulge. I refused to participate in sports carnivals, because they insisted that everyone wear shorts. I never even learnt to swim because I’d never,ever wear bathers.

My mum is bipolar, and she was always in and out of psychi atric wards when I was growing up. In fact, a family member told me I was conceived in one. My mum’s condition had a large influence on everyone in my family, but challenged her the most. She’s a smart, caring and nonjudgmental person who was deeply maternal, but the medication the doctors put her on really dumbed her down.

When the meds stopped working or when she’d refuse to take them she’d get sad and cry a lot, or would stay up all night babbling on about things that made no sense, and laugh hysterically. My dad was deeply avoidant and just buried himself in his work.

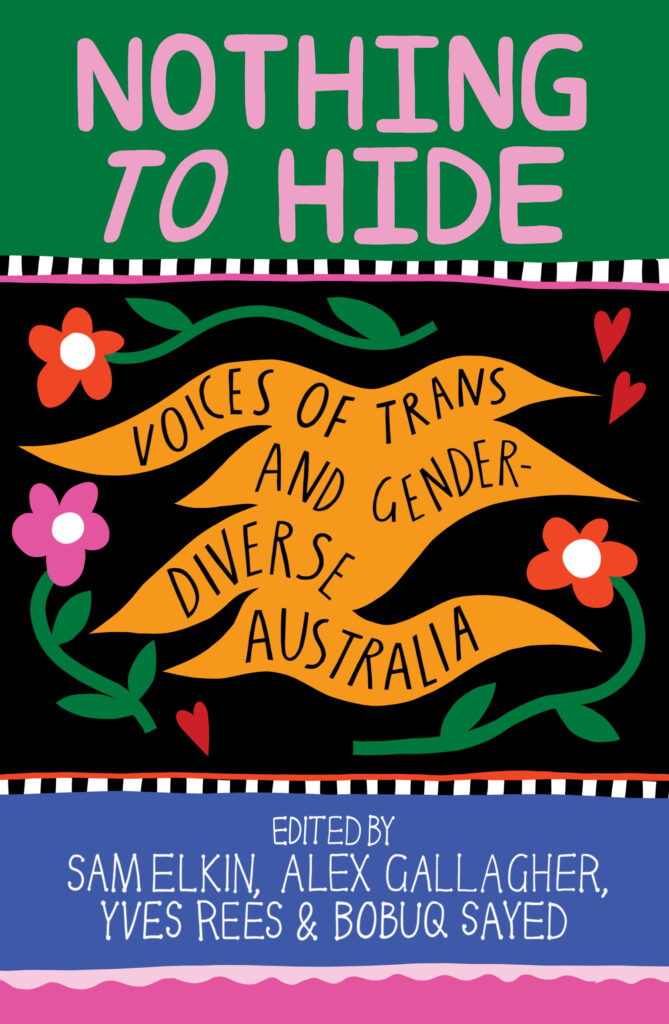

Cover image: Nothing to Hide: Voices of Trans and Gender Diverse Australia. Picture: Supplied

When I was 10, my parents separated for good. My mum took me up to NSW and my sister stayed in Victoria with Dad. I got sent back down to Victoria to see Dad from time to time, but I didn’t know how to act like a proper boy, which I knew I had to do in front of him. It made me feel awkward and withdrawn. My mum was either dumbed down from her medication or she was in hospital. I felt so alone, with no one I could tell my secrets to.

I started missing so much school that the truancy officers started knocking on our door. My dad was so worried that I was falling behind that he got a Family Court order to say that I had to see a child psychologist. When I went to their office, the psychologist held up a picture of two dogs having sex and asked me if anyone had ever done that to me.

My first thought was, ‘No, this is the first time an adult has shown me pictures of animals having sex, you pervert!’ They didn’t ask me anything about wanting to be a girl, and I didn’t know how to bring it up. They declared me a strange, troubled boy, and sent me back to Victoria to live with my dad and my sister.

When I got back to Victoria, my sister told me I was gay. She tried to tell me that it was okay to be gay, and that I shouldn’t be ashamed. I kept telling her I wasn’t gay, but she didn’t believe me.

Her boyfriend at the time wasn’t as nice about it. He called me ‘fag boy’, and would stick his tongue in my ear and ask me if I liked it. I didn’t, it made me feel upset and dirty. My dad joined in, and started calling me ‘poofter’ as a nickname.

My dad decided I needed to be toughened up, and he sent me to a Catholic boarding school, wherethey trained us to be ‘Christian soldiers’. All weekend, we were made to march or pray to Jesus. I didn’t fit in, and the boys kept themselves entertained by taunting me. They covered me in shaving cream while I was sleeping and heated up bits of metal with lighters, burning me with them, which scarred me for life. It got so bad that I ran away from school one night and slept in a public toilet. I called my mum the next day, and she drove down from NSW to come and get me.

I think my dad gave up on me after that. Back at Mum’s, I enrolled in a new school, which I was hoping would be a fresh start. I decided to make myself over as a ‘metal head’. I grew my hair long and got a guitar that I never did learn how to play. I would blast ‘Cemetery Gates’ by Pantera so loud that sometimes the police would come round to tell me to turn it off. I started smoking and drinking, and Ioften hosted drunken parties at my place when Mum was in the psychiatric unit. I stopped eating and lived off coffee and alcohol, and I lost heaps of weight.

Eventually people started mistaking me for a girl because I was so skinny and longhaired. Whenpeople got a better look at me they would all react differently; girls would usually say sorry, assuming they’d offended me. Guys would do adoubletake and then call me a ‘fucking faggot’.

When they pointed and yelled this at me out of car windows, it reminded me of the audience on the Jerry Springer show, treating the transgender people like circus freaks. I imagined how much worse things could be if I actually transitioned.

Eventually, I dropped out of school altogether. I stayed up all night drinking and smoking and playing PlayStation. Somehow, I got a girlfriend, and for the first time in my life I felt I finally had someone I could trust. She would come over, stay the night, get changed into her school clothes and go to school, leaving her original outfit behind. All her clothes fit me really nicely, which I’d wear alone in the house while she was away. I thought I looked pretty nice, and things were going well between us. I even started to consider telling her about the real me.

Instead, one night she looked at me and told me she wanted to cut off my hair. ‘It looks too girly,’ she said. ‘What’s wrong with that?’ I replied. She disclosed to me that her dad, who was no longer in her life, had had a ‘sex change’ just before she’d met me.

She said that she’d never forgiven her dad, and that she’d sent him a letter telling him that she hated him and wanted nothing to do with him. While she told me this story, she kept using ‘him’ over and over again.

‘He’s dead to me,’ she said as she ended her story. I was devastated to discover that the first person I felt I could trust hated transgender people. I felt more alone than ever.

I started to feel that my body was a stranger’s. I hated what I saw in the mirror. I didn’t know who Iwas or what to do, so I just drank, smoked and slept with every girl I came across. My girl friend and Isplit up, and I moved up to Newcastle. In 2000, I was such a drunken mess that when the Olympic torch went right past my flat, I was too smashed to even stick my head out the window and look.

My flat was practically empty of furniture, and there was even a bullet hole in one of the windows thanks to some local criminals who did a driveby shooting at my house after I pissed them off somehow. When 9/11 happened I only found out because they interrupted DragonBall Z—the only show I’d wake up before midday to watch—to show the footage.

I had a new girlfriend by then. I often asked her to dress me up in her clothes, which were little miniskirts and tight cocktail dresses. My favourite was a green velvet dress that I paired with some knee high boots. She said I looked better in it than she did, which meant a lot to me, but we ended up splitting up because of my drinking.

My dad put a lot of pressure on me to move back to Victoria, because he was worried that I’d die or end up in jail if I stayed in Newcastle. He gave me a job in his office, where my brother also worked, and I got to know him a little. I told him that Dad thought I was gay, which really frustrated me because I knew that I liked girls.

Determined to prove how not gay I was, I slept with every girl that I could. I even called my dad to tell him I wouldn’t be coming into work as I’d torn my penis during sex. My brother, who overheard the conversation, drove over to see if that could really happen, and went really pale after seeing all the blood.

I eventually got sick of my dad’s homophobic taunts, and decided to try and get my high school certificate at Victoria University. I made some nice female friends who also thought I was gay, mainly because I had stopped trying to have sex with women all the time. I had replaced that addiction with playing World of Warcraft obses sively as a female character. My beautiful avatar was a Night Elf, who was tall with long, platinum blonde hair past her waist, and an everchanging array of dresses that noone could take off her.

A beautiful girl started coming over and just sitting with me while I played World of Warcraft. She called me at night and we’d have long phone conversations, talking about anything and everything, and that’s how I started falling in love with her. She seemed to truly care about me.

We started dating, and soon after I asked her to dress me up in her clothes. She put me in a stunning blue dress that matched my eyes. I asked her if she’d still love me if I was a girl, and she said that she would as long as she could see my beautiful blue eyes. But she didn’t think I was serious.

Despite my new love, I was still drinking a lot and got arrested for drunkenly climbing the roof of a restaurant, apparently looking for a table with a view. I got charged and pleaded guilty, and copped a big fine.

My girlfriend became pregnant, and soon we had two beautiful baby girls. We married, and I landed a job as a maritime security officer. I was desperate to get on the straight and narrow to support my family, and I swore off booze and smokes.

One night, I asked my wife if she’d leave me if I got a sex change. She thought about it, and said that she definitely would.

I was crushed. It brought me right back to the shame I felt when I’d first seen the audience laughing at Jerry Springer’s transgender guests. I started drinking again. I was passive aggressive, and increasingly painful to be around, as I projected my unhappiness onto everyone around me.

My house stopped feeling like my home, it just felt like a stranger’s. I had such bad anxiety that I developed an eye twitch and had trouble swallowing food. I kept drinking more and more, and alienated my family through my increasingly toxic behaviour.

“I started to feel that my body was a stranger’s. I hated what I saw in the mirror,” writes Stacey. Photo: Shutterstock

One day, my kid’s teachers got so concerned that they called child protection, who started asking me lots of questions about domestic violence and child abuse. Pretty soon, the police took over asking all the questions, and I ended up in jail.

When I finally got bail, I moved in with my nan and my mum, who were living together back in Victoria. It was at my nan’s house that I really had time to stop and think about what I’d done, and how I had pushed everyone away with my awful behaviour. I decided that since I was now a complete outcast,I might as well transition after all. How could things get any worse? I went to court back and forth, and disclosed to my defence lawyer that I was transgender.

My lawyer disclosed this to the judge during my sentencing hearing. The judge said that I wouldn’t have any trouble with that since I wouldn’t have access to women’s clothes anyway. The judge said that I could minimise my harassment by growing a beard, cutting my hair and using my deadname. Basically, don’t be trans and you won’t be harassed. It really made me wonder about how out of touch the people who decide our fates really are.

In prison, I began an epic battle to receive genderaffirming health care with longstanding help from a community legal service. It took years to get a referral from a doctor to get on hormone replacement therapy, to be allowed female clothing and for staff to refer to me with female pronouns. I’ve been on female hormones for years now, but I am still not allowed to legally change my gender marker as the government says it may ‘offend’ the community. I’ve only stayed sane because of an incredible social worker who has volunteered their time to support me and help me lodge endless paperwork.

A men’s prison is not a safe place for a trans woman. Since I’ve been inside, I’ve been bullied, bashed and raped. I have nightmares most nights and I have tried to end my life many times. If it wasn’t for the external support I’ve received, I probably would’ve kept on trying until I succeeded.

Despite the cruelty I’ve been exposed to in prison, I’m still glad that I finally know who I am. I’ve learnt that I can live without alcohol, and that I don’t need sex to make me happy. I am still haunted by some of the things I have done, and I am terribly sorry about the harm I’ve caused to the people who loved me. I wish I had been able to live as my true self when I was younger, as I might’ve been able tospare many people a great deal of pain and projected anger.

I still haven’t gotten out of prison yet, and some days it’s tough in here. But I am grateful that my body is now mine, and that I am starting to love the person I see in the mirror.

Nothing to Hide: Voices of Trans and Gender Diverse Australia is out now.

- Please note: the photos in this story are stock images.

128