In this article – which is both personal and research-based – Lisa Wheildon explores the events and social changes that led her to publish a paper about “The Batty Effect” in the journal Violence Against Women.

I clearly remember the moment, seven years ago now, when then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull made a statement that would make headlines around Australia and mark a significant shift in public discourse and policy on domestic and family violence (DFV). It was also a moment that motivated me to examine the role of survivors of DFV in driving change.

In 2015 I worked at Our Watch, Australia’s foundation for preventing violence against women and children, and I watched Turnbull’s announcement huddled around a monitor with my colleagues.

Among many things Turnbull said that day, he memorably said, “Disrespecting women does not always lead to violence. But all violence against women begins with disrespecting women.”

What was remarkable about those words and the rest of his statement was that Turnbull centred gender equality as key to ending DFV.

As Judith Ireland wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald, “Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has called on all Australians to make a “cultural shift” and stop disrespecting women, declaring that gender inequality lies at the heart of domestic violence.”

Another reason the statement was significant was that until earlier that month (September), Tony Abbott, a man with a reputation as a misogynist (as exemplified by Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech), had been Australia’s Prime Minister and self-appointed Minister for Women.

Lisa’s research shows Rosie Batty’s experience prompted stakeholders to overcome institutional and ideological barriers and work together to bring about change. Picture: Supplied

Before Turnbull’s speech, DFV advocates and organisations had been reluctant to speak explicitly about the gendered drivers of DFV, including stereotypes and social norms about what it means to be male/masculine and who makes an ‘ideal’ victim. Organisations were concerned about jeopardising their funding and alienating potential supporters.

Turnbull’s statement was also significant because he made it when announcing one of his government’s first decisions—a women’s safety package of over $100 million—and with Rosie Batty, survivor advocate and Australian of the Year, by his side.

What’s more, it was revealed at the announcement that Rosie had provided advice on the reform package.

Turnbull’s statement indicated that not only did his government recognise the causes of DFV and what it would take to end it, but they would prioritise the issue and listen to survivors.

The Batty effect

Rosie’s 11-year-old son Luke was murdered by his father in February 2014, and she has been in the public spotlight ever since. Rosie repeated the message that gender equality is central to preventing DFV throughout her advocacy as Australian of the Year.

By January 2016, she had spoken at approximately 250 events and addressed more than 70,000 people. She had also inspired Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews to commit to an Australian-first Royal Commission into Family Violence (see Facebook post below).

The Commission led to a record investment of approximately $4 billion in DFV funding in Victoria, more than the total funding commitment to DFV across all other Australian states and territories and federally.

Source: Facebook Premier of Victoria Daniel Andrews (July 2018)

Shortly after Turnbull’s announcement, a stalwart of the DFV sector told me that she had never seen a period of such significant change in all the decades she had been working in the area. She felt Rosie was critical to the transformation.

My interest was piqued because I knew how slow policy reform could be, having spent ten years working in the Victorian public service. I wanted to know how we could maintain and maximise this momentum.

Now seven years later, I have had my research on the Batty effect published in the journal Violence Against Womenand recently submitted my PhD for examination.

A national emergency

DFV is one of Australia’s most serious social problems. It is prevalent, with one in every four women in Australia experiencing physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner (since age 15).

Police are called to a family violence matter every two minutes, and on average, one woman is killed by her current or former partner every week. While no postcode is immune to DFV, its effects aren’t even.

There is evidence that women with disabilities in Australia are around two times more likely than women without disabilities to have experienced sexual violence and intimate partner violence.

DFV is also persistent. Despite efforts to reduce DFV, surveys show that partner violence rates have remained relatively stable since 2005. Recent data suggest DFV has increased and become more severe during the COVID pandemic.

Survivors as change agents

The emergence of survivors of DFV as policy change agents is a relatively new development and has not been well researched. I felt it was important to examine just what role Rosie had played in bringing about a period of remarkable change on DFV.

How can survivors help prevent what Natasha Stott Despoja, a member of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, has called Australia’s national emergency?

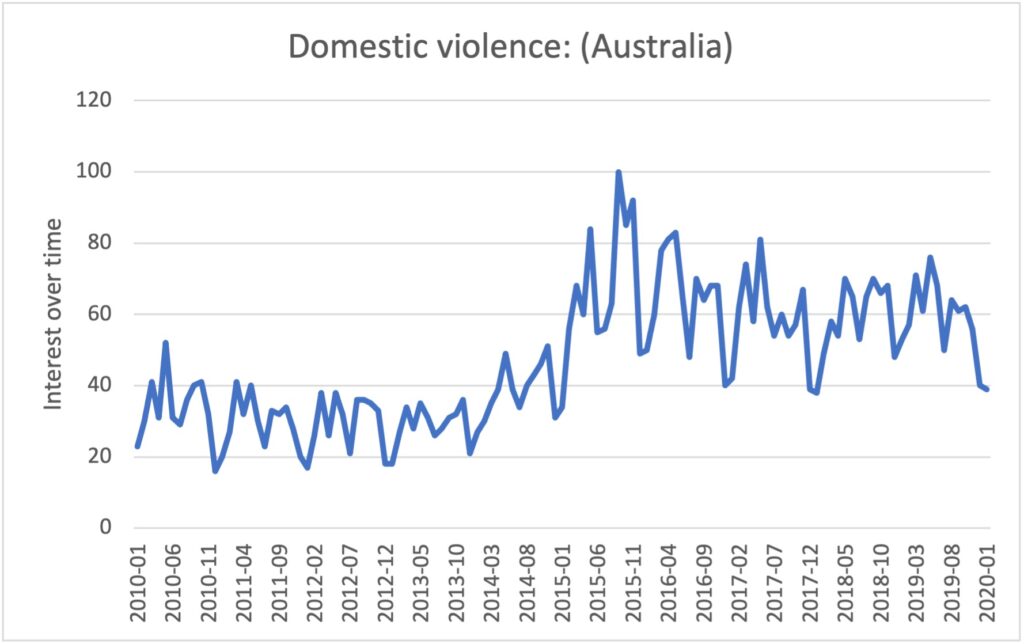

Firstly, I confirmed that there had indeed been a significant increase and change in public discourse regarding DFV and that it coincided with Rosie’s advocacy. A search of Google trends data indicated that DFV had become more prominent since 2015 (see Figure 1).

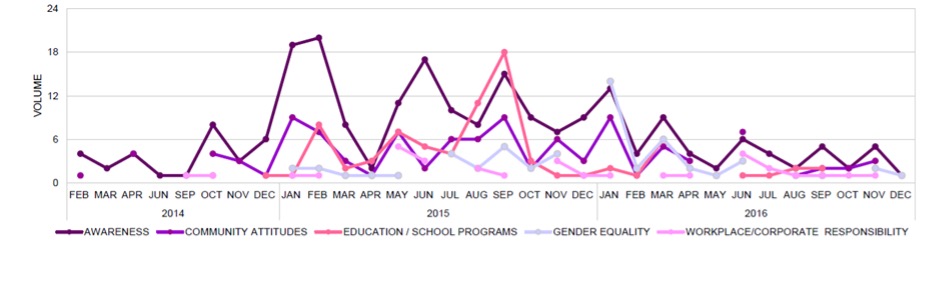

An analysis of media coverage between 2014 and 2016 found that 95,261 media reports mentioned Batty and that as the level of interest in the issue increased, the nature of the discourse changed. For example, media coverage regarding general awareness decreased as strategies for reducing DFV, including school programs and gender equality, grew in profile (see Figure 2).

These were messages that Rosie consistently reinforced through her advocacy.

Figure 1. Ten-year Google trends search for the term domestic violence in Australia (2010-2020)

Figure 2. Primary prevention media trend analysis: 1 January 2014 – 31 December 2016

Secondly, I found that Rosie possessed a range of personal characteristics and adopted strategies that made her a particularly influential change agent. Most notable were her ability to put herself in other people’s shoes and understand their objectives and her capacity to build networks of people with the expertise needed to make change happen.

My interviews with Rosie and policymakers also revealed additional attributes and contextual factors key to Rosie’s success. One of those factors was the horrific nature of Rosie’s experience and the urgent response it demanded.

This motivated stakeholders to overcome institutional and ideological barriers and work together to bring about change. Other important factors were the window of opportunity opened through the change of government in Victoria and the decades of work undertaken by women’s movements, which provided solid foundations for change.

Next, the study exposed significant challenges facing survivor advocates, including the corrosive power of the social norms of the ideal victim and victim-blaming. These insights help explain why some survivors—including First Nations peoples, people of colour and people with disability—aren’t heard and present limitations for policymakers.

Finally, the study revealed the pressure Batty felt to be compliant and avoid upsetting or becoming a threat to powerful interests. The recent experiences of Grace Tame, Brittany Higgins and others have highlighted these pressures on survivors.

Eliminating DFV must be a national policy priority for Australia. Harnessing survivors’ influence and lived expertise to increase understanding, improve services and policies, and end DFV is critical.

But it must be done properly. As Grace Tame said at the 2021 National Women’s Safety Summit, “We need an approach that is not siloed, we need to be recognising that there are policy and decision-makers, experts, as well as lived experience survivors who need to participate in the discussion.”

- Feature image: Australian of the Year Rosie Batty speaking at the Women’s Lunch on Day One of the 2015 ACTU Congress. Photo credit: ACTU/Jorge de Araujo. Used with full permission from the ACTU.

Dr Lisa Wheildon is a research and teaching associate in criminology at Monash University, UNSW and RMIT University. Lisa's PhD research examined the role of victim-survivors with lived experience of gender-based violence in co-producing public policy. Lisa has recently worked on research projects regarding online safety, technology-facilitated coercive control and workplace technology-facilitated sexual harassment. Previously, Lisa worked in senior roles in the Victorian Government and helped establish Our Watch, the national foundation for preventing violence against women and children.