In early August 2022 we marked National Missing Persons Week – a time when the Australian community can reflect on the stories of loss relating to those who have vanished, and those who are left behind. This year saw the largest number of police reports, relating to the safety and wellbeing of a person, with just over 51000 reports made about the whereabouts of a vulnerable person.

That’s almost 150 reports a day.

Missing Persons has the complete fascination of the community, the popularity of true crime means that there is often a significant disconnect between the reality of missing persons and the armchair detective experience.

That experience is facilitated by podcasts like The Teacher’s Pet, docuseries’ allowing you to watch a case unfold and closed Facebook group speculations about the whereabouts of a person. So, what is the true lived experience of a person left behind when someone is lost?

Almost 3000 families in Australia are classified as families of long-term missing people. A very small percentage relate to people who were the victim of a crime – mental health concerns, young women from First Nations communities, older women with dementia and misadventure are more likely the scenarios related to disappearance. A long-term missing person is one whose absence has exceeded six months, and can sometimes refer to years, or decades waiting for those last pieces of the proverbial puzzle.

The experience of loss for those families is referred to as an ambiguous loss, a phrase used by an American Emeritus Professor – Pauline Boss – relating to her landmark work with families who had a family member missing in action. That loss is a harrowing, haunting experience.

My PhD study, on the experience of hope for families left behind when someone is missing, identified that the loss is a ‘teasing journey’ of both hopefulness and hopelessness. It is a loss that does not get easier over time, the lived experience stories of families of the missing suggest it gets harder. The more they seek news, the less sure they are of the outcome. The more they share in the media about their loss, the more ideas people suggest about what may have happened. It is unresolved – both physically and psychologically.

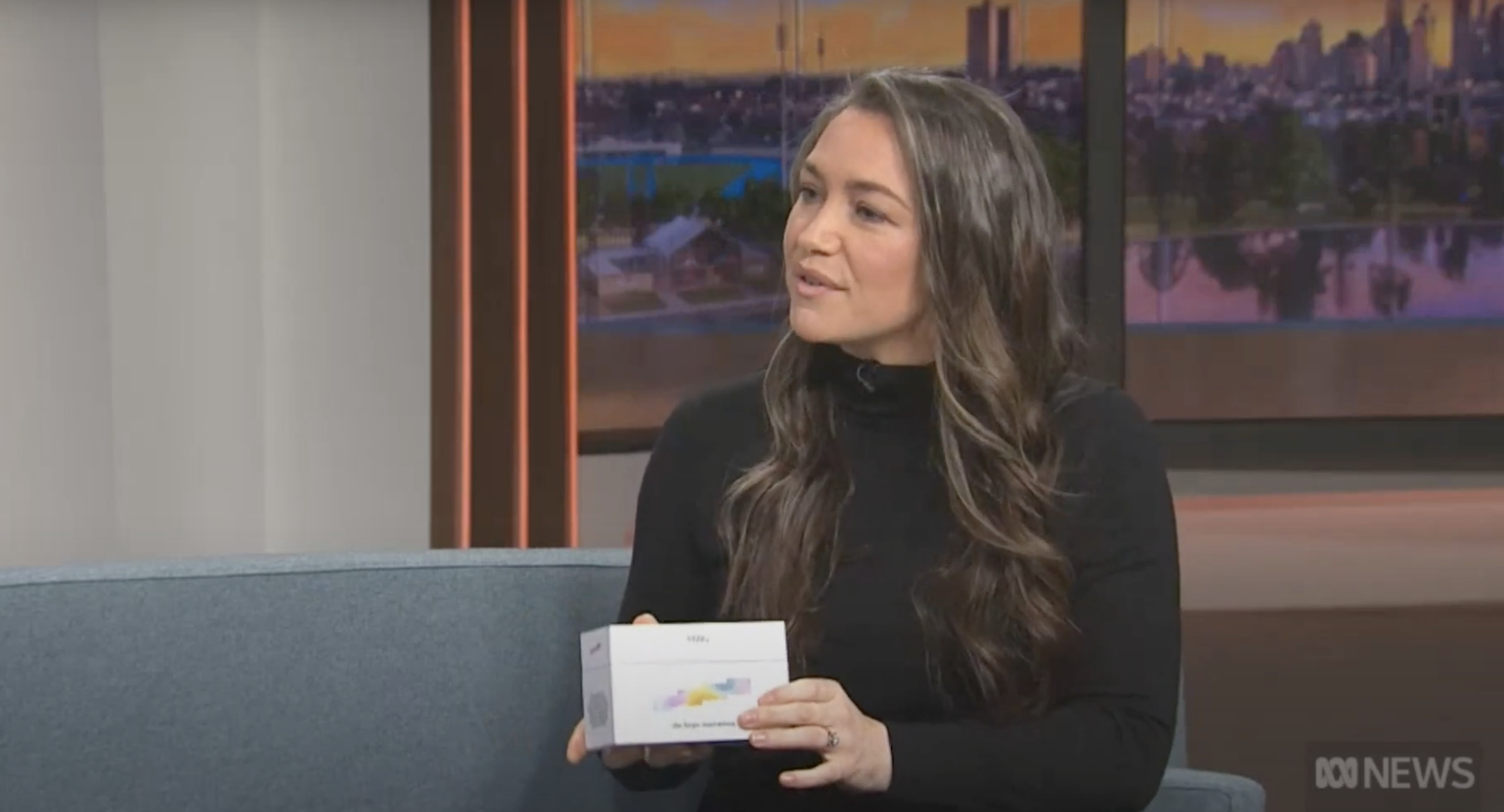

Loren O’Keeffe with “The Hope narratives,” a box collection of reflective statements for families left behind. Picture: Supplied

A decade ago, I met Loren O’Keeffe – she was searching for her brother Dan. He had disappeared from Geelong, and she undertook a massive social media campaign called ‘Dan come home’ in her 5-year effort to locate him. What we found in working together, me as an academic researcher, her with lived experience passion and commitment to her own journey and to other families of missing people in Australia, was a shared goal to reduce the isolation of other families of the missing.

Last month we launched, after a year in development with communications company whiteGREY, was: The Hope narratives, a box collection of reflective statements for families left behind, both here and internationally, to reflect on their journeys with hope while waiting for news about their missing person.

Loren’s words shaped the approach to creating the cards: ‘When a loved one goes missing, there is no right way to deal with it. You oscillate from hope to hopelessness, overwhelmed by the physical, mental, and emotional burden, often feeling no one understands what you’re going through’.

Alongside a group of long-term missing families, over some tough days in Melbourne, we captured reflective statements on the hard truths of having someone missing, ideas like a simple walk down the street could result in repetitive scanning of faces, to see if you could spot them.

We captured new coping ideas; like reminding yourself that whilst today might not be the day you find them, you may one day. And then explicit acts of hope like reminding families to focus on what is present, and that resting and gathering strength to navigate another day is sometimes the only option available.

“The Hope narratives,” a box collection of reflective statements for families left behind. Picture: Supplied

Our hope, as two women pushing for change in a law enforcement heavy sector, is to see these cards used to start conversations – in counselling, within family chats when someone is missing, by journalists trying to grapple with the complexity of ambiguity, and most importantly for families as they wait for news.

I started working in missing persons 18 years ago, and very early on a family reminded me that it was ‘the hope that hurts’. Collaborating with families on this project brought that home once again, however this time we can provide a tangible tool to navigate that hope, provide respite and offer connection when the outcome remains uncertain.

- Feature image: Loren speaks on ABC News Breakfast about the project. Picture: Supplied

Dr Sarah Wayland is a missing persons and trauma researcher at the University of New England.