Last month, feminist editor and writer Zoya Patel delivered a speech at the Canberra Labor Club that blew the crowd away. Through the lens of her own family, Zoya reflected on how gender bias impacted the women she loves. How might life have been different, if those women had had equal opportunities? The text has been lightly edited for readability.

According to Our Watch, First Nations women in Australia are nearly 11 times more likely to die due to assault and twice as likely to die due to domestic and family violence compared to non-Indigenous women.

The average life expectancy for First Nations women is more than eight years less than non-indigenous women.

I want to note that any Australian movement for gender equality that is not led by First Nations women, grounded in a commitment to reconciliation, and that doesn’t prioritise closing the gap between First Nations women and non-Indigenous women, is not a true movement for equality.

I want to ponder what would have changed for the women in my life had they not had to contend with gender bias.

First, a little about me. I’m 32 years old – and I say this because I know appearances can be deceiving. I was once asked by religious doorknockers if my parents were home, when I was 27.

So, I’m 32, and I’m Fijian-Indian. I have lived in Australia since I was three years old, and have called Canberra home for most of my life. My ancestors span numerous countries and continents, starting in India, and ending all over the world.

My maternal grandmother was a nurse in Fiji. She came from a family of few means, the eldest of 13 children. Her own mother had her first child in her early teens, from the marriage that was arranged for her when she was just a girl.

My grandmother was an incredibly intelligent woman. The cultural norms that dictated her coming of age did not value intelligence in women, but she was lucky in that her family supported her to study and qualify as a nurse. At that time, the thought of an unmarried woman studying to become a doctor was very uncommon. So, she was a nurse, she married, she had three children.

She lived a humble life and was widowed young. She died in her early 70s.

If my grandmother had not contended with the gender bias that saw women’s first priority as being the home, perhaps she would have been a doctor. The bias against women-dominated jobs meant her pay as a nurse was meagre, although it still contributed considerably to the household, where my grandfather was a taxi driver. If this bias didn’t exist, perhaps my mother’s experiences of childhood would have been less defined by poverty, and she and her brothers would have been able to access a higher standard of living than their parents.

My mother, like her mother before her, is very intelligent. She studied to be a teacher, but when we moved to Australia when I was a child, she left her teaching career behind in Fiji.

Her reasoning was that, given the systemic racism that permeated so many parts of Australian society, she was afraid of the students she encountered not respecting her or other teachers presenting an issue, possibly being prejudiced.

Here, mum was responding to what she saw around her. We arrived in Australia in the early 90s, when racism in politics was rife, led by Pauline Hanson, the founder and leader of the right-wing populist political party, One Nation. We were living in a country town, and faced racism regularly – at my parents work, at our schools, on the street.

If this racist bias didn’t exist, perhaps my mother would have requalified as a teacher in Australia and pursued her passion for knowledge further. But instead, she worked in supermarkets for years, before my parents eventually bought their first business.

Mum also had to navigate the gender biases and norms of both our Fijian Indian culture, and Australian culture.

This meant she prioritised the needs of her children, her husband and her community over her own. It means that she ignored the growing aches and pains in her body for years, not realising they were the early signs of the debilitating autoimmune condition that now defines her life. Had she been treated earlier, perhaps she would have been able to go into remission, instead of being nearly crippled by the disease.

In fact, mum did visit a doctor in her thirties to complain about the swelling in her joints. The doctor told her she was imagining it, that she was bored or anxious now that all four of her kids were in school. He suggested she get a hobby, didn’t run tests, and it wasn’t until a decade later that she was diagnosed.

If women’s bodies weren’t seen as public property, and women’s experiences of health not dismissed as hysteria, would my mother have a better quality of life now?

I have two older sisters, a blessing which I am very grateful for.

When my sisters and I were growing up, we were trapped between the conflicting expectations of women in Australia in the early 2000s and in our Indian Muslim culture at home.

On one hand, contemporary culture sexualised women and objectified our bodies in the media, advertising and music industries. On the other hand, we were expected to be modest and chaste in our religion and culture.

We watched Spice Girls music videos on the weekend, where girl power was defined as a sort of aggressive sexuality, and then heard sermons at the mosque about the importance of female modesty, as a form of protection against male urges.

One community saw the other as oppressed, and the other saw the first as immoral. This is an oversimplification, but the contradiction felt very real to us, and it was both confusing and frustrating because both views relied on a rigid set of expectations about women and femininity.

I watched most of the girls around me at school obsess over their appearance – particularly their weight – and place a very high value on male attention and approval. Those among us who weren’t heterosexual or cisgendered suffered ostracism, judgement and bullying.

I wasn’t immune either – I hated the way I looked, I was insecure about how others perceived me, and despite my outward feminist persona, I was desperate to be liked and accepted, like most adolescents.

But imagine if our culture didn’t perpetuate the objectification of women’s bodies. Imagine if myself, and the young women I grew up with, were encouraged to pursue the growth of our intellects and creativity over our sexual capital. Imagine if, instead of being pitted against other women in competition for male attention, we were enabled to collaborate and come together in the pursuit of our shared goals.

It’s hard to envision what that world, free of bias, could have looked like, and partly that’s because our reality today isn’t that different to the past.

The same biases that have influenced three generations of the women in my family, persist to this day.

The expectation that women must prioritise the home, children and their families to a greater extent than male partners or family members; the trivialisation of female-dominated industries, women’s health, and the contributions that women make to our communities; and the obsession with women’s appearances, the objectification of our bodies, and the equation of our worth with male approval.

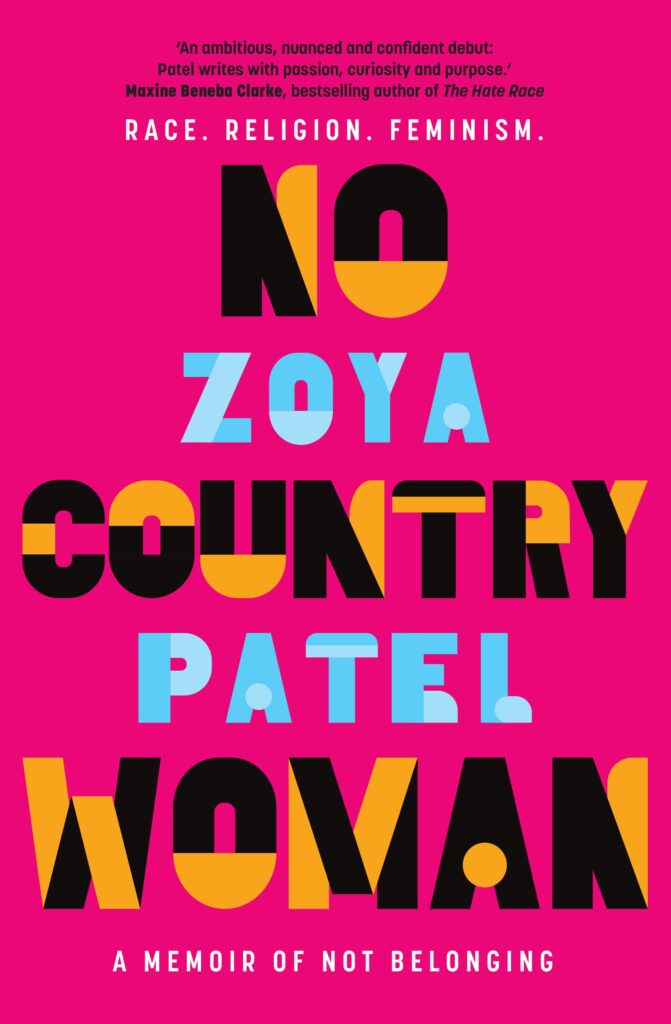

The cover of Zoya Patel’s book, No Country Woman: A memoir of not belonging

Every year, we make progress, but every year we also uncover yet more examples of how gender inequality persists in our communities. Remember – for every Grace Tame, or Brittany Higgins, there are thousands of unknown and unnamed women who have suffered abuse and assault with no attention and no consequence for their perpetrators.

Among these women are the many Indigenous women, women of colour, queer women, trans women, disabled women, and other women who don’t fit the criteria of acceptable victimhood, who have not only been ignored, but often who have faced discrimination and been retraumatised by the systems that are meant to protect them.

Biases don’t have to be bad things. There is such a thing as a positive bias. We could, as a society, be more inclined towards believing victim survivors of assault and violence, for example, than disbelieving them when the evidence lies in their favour.

We could be more inclined towards celebrating the diversity of women’s contributions, instead of trivialising or dismissing them.

We could be more inclined to supporting policies and programs that seek to accelerate gender equality, than to reinforcing patriarchal systems of inequality.

I have four nieces and a nephew, and watching them grow up has shown me that every generation starts with a foundation that is more solid than the generation preceding them. Already, my nieces and nephew are proving to be more emotionally intelligent, empathetic, and fierce than we were, and it excites me to think of the futures they have ahead of them.

I know that their parents, and their aunts and uncles are determined to break as many biases that they may face as possible. After all, if we all dedicate ourselves to changing the corner of the world that we’re in, eventually, those corners will meet up and form a whole.

- The Labor Club event where Zoya gave this speech was in support of the Canberra-based service, Toora Women Inc, which supports vulnerable women in the region. Find out more about Toora here.

Feature image: Supplied

Zoya Patel is a writer and editor based in Canberra. She is the Founding Editor of independent feminist journal, Feminartsy.Zoya is the author ofNo Country Woman, a memoir of race, religion and feminism. Her upcoming novel, Once A Stranger, will be published in 2023.