Britney Spears. We’ve all heard bits and pieces about her fight to regain guardianship of herself from her father. In the US they call this conservatorship and according to the BBC, it is “…granted by a court for individuals who are unable to make their own decisions, like those with dementia or other mental illnesses.”

I must admit I’m not an expert on the details, but I see control. Lack of autonomy. Lack of decision making power. Being infantilized. Having not only her sense of control taken from her, but also in practicality. And I see the outpouring of human concern for her. The empathy, the sympathy, the worry.

And then I think of Ann Marie Smith, the disabled woman in South Australia who was totally reliant, through physical disability, on other people. And her final days, months reliant on a carer who didn’t care.

But she had no voice, no court to go to, no legal service to access. She was totally at this woman’s mercy. And a benevolent mercy it was not. So she was left, left to die from something that should never happen to any human. And would not happen, to a human who could walk.

That’s it, the ability to walk and communicate. She was considered rubbish, superfluous, because she couldn’t walk or talk. But I’m sure she felt. I’m sure she felt every last terrifying moment. That, my friends, is ableism, in its cruelest form, and its most fatal. This is one reason why, Women With Disabilities Australia submitted to the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability that all restrictive practices “are violent and are in violation of human rights” and should be abolished. A ‘restrictive practice’ means any practice or intervention that has the effect of restricting the rights or freedom of movement of a person with disability. It includes confining someone to a chair, like Anne Marie or imposing a guardianship, like in Britney Spears’ case. It’s ableism.

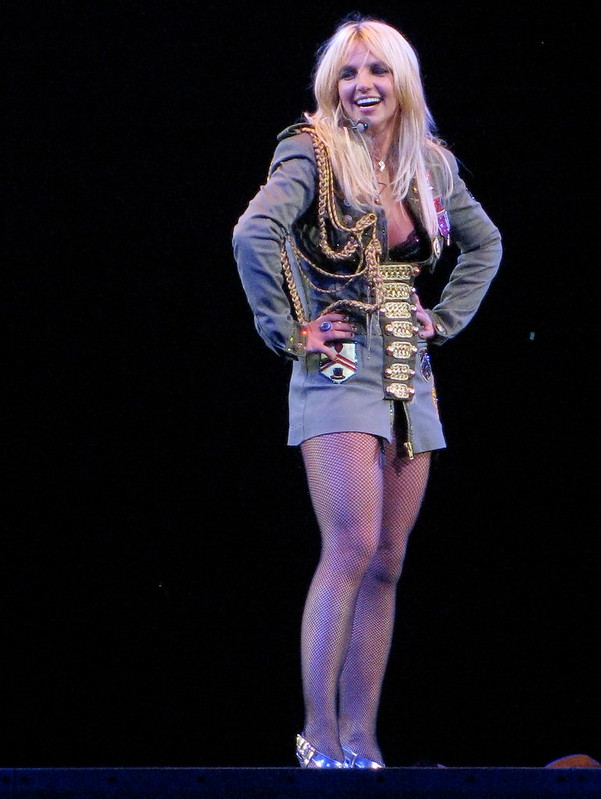

Britney Spears at a Montreal Concert. Picture: Anirudh Koul. Posted here under a Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC 2.0)

I see ableism every day, in a more insidious, hidden form. But at its very core, its an assumption that you know better for this person, that you understand their situation. But you don’t.

Personally, I’ve been not disabled and disabled. I feel it’s a gift. It’s a gift to see the different ways in which the world treats you. It has illuminated for me a whole other world that I didn’t know existed, as I spent the first 35 years of my life being conditioned only to privilege. I call it the straight up benevolent assumption.

When you interact with people and institutions, the assumption that you mean well is in-built. And it teaches you that the world will mostly deliver. And it did. And again, with privilege, it still does, but since becoming disabled, I have a new lens. The in built assumption from others and institutions is not a forgone conclusion for so, so many. Being given this lens and sense of perception part way through life has been for me, like a light shining on the inner workings of the human race.

When I woke from my stroke, I couldn’t physically talk. I could understand, make language if someone passed me a letter board, but I had lost the nerve to make the mechanics. It has gone offline, care of brain haemorrhage.

All of a sudden, I was an infant. I was talked over, I was talked about in my presence. What I wanted or needed was assumed.

Until I started doing things like yanking really hard at people’s beards with my good hand because I was so furious. And until I could start slowly talking again. I noticed even the rehabilitation doctor make more eye contact with me once I had a few words. I was like, wow, even you. (If you read academic research around disability, you will find the word “infantilized” used over and over again.)

And because I lived a life of privilege, I was confused. What is going on? It was so stark, from one day to the next. Any ordinary day indeed.

My days and months of losing my sense of autonomy is nothing on the years and lifetimes that so many humans experience. Feeling. No one doesn’t feel. The physical stuff is our mortal shell. But the feeling is what hurts our heart and heads. Or make it happy. I’m sorry we failed you Anne Marie, but I’m not surprised. And embrace your freedom Britney.

Feature image: Ann Marie Smith, provided by the South Australian Police.

Hannah had a brain stem haemorrhagic stroke in 2017. She was 35 years old. Entering the world of disability had been challenging, life enhancing and illuminating.