In recent negotiations on behalf of a woman who was sexually harassed at work, I found myself in an unusual position. My client sought an NDA (non-disclosure agreement). They generally prohibit all parties to the agreement from talking about the claim to anyone. She continues to wrestle with the trauma that her experience caused and didn’t want public attention on what had happened to aggravate the problem.

Her employer was having none of it.This company has recently adopted a policy of not entering into NDAs in cases of sexual harassment as part of a renewed focus on providing a safe workplace for women. In the end, we agreed to a compromise whereby the fact of the sexual harassment could be disclosed but my client’s identity remained shielded.

Let me undercore this – any company NOT wanting an NDA in a case like this is highly unusual. For decades, NDAs have been the standard price of settling a sexual harassment law suit. With few exceptions, it’s been a case of no NDA, no settlement.

Late last week, California was the source of another tectonic shift in the battle for gender equality when Governor Gavin Newsom signed the Silenced No More Act into law. The new law extends a ban on the enforcement of NDAs in sexual harassment cases to all cases involving unlawful discrimination.

A similar move is underway in Ireland with the tabling of the Employment Equality Bill by Senator Lynn Ruane who argues that “it is simply untrue and a further manipulation of a victim to imply that settlements require NDAs. They are required to protect employers’ reputations and perpetrators’ identities. If it was in the best interest of the victim then it is only the victim they would protect.”

There is no doubt that NDAs have protected higher status perpetrators at the expense of the interests of their victims. They have operated to shield the true extent of sexual harassment and gendered violence from us all. This has also impeded the ability of researchers to study the problem with a view to assisting in minimising it. I have repeatedly had to tell academics wishing to conduct research into sexual harassment that my clients are unable to assist them because of their NDAs.

NDAs are another reminder that we live in a brand-driven world. In recent decades, businesses have turned away from production and direct employment in favour of investing heavily in brand development and management. Anything that may tarnish the brand has become anathema. Since the 1990s, the use of NDAs has exponentially increased. Many US companies now sign their staff up to non-negotiable employment contracts that ban them from saying anything critical of the company in perpetuity.

Brand management does not sit comfortably with fundamental human rights.

The Royal Commission into Child Sexual Abuse showed how religious institutions used NDAs to try and hide the systematic extent of child sexual abuse in their ranks.

Journalist Jenna Price argues that NDAs are “a vile legal instrument that silences women and covers up the behaviour of sexual harrassers at all levels and in every sector in Australia.” While there have been calls to ban NDAs about sexual harrassment in Australia, to date that approach has not been embraced. Earlier this year Federal Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins delivered her major report, Respect@Work, which discusses reforms to the use of NDAs.

“The Commission heard about the benefits of NDAs in sexual harassment matters in protecting the confidentiality and privacy of victims and helping to provide closure,” the report says. “However, there were also concerns that NDAs could be used to protect the reputation of the business or the harasser and contribute to a culture of silence.”

The Commission went on to recommend that guidelines be produced that identify principles for the use of NDAs in workplace sexual harassment cases and that possible further regulation of NDAs be considered.

The issue is not straightforward. While some women do want to speak out, a significant number of women who suffer sexual harassment are not comfortable with the details of their traumatic experience being disclosed to others. There can be many reasons for this including shame, guilt and fear of further adverse consequences.

We had our own Safety Summit tonight.@BrittHiggins_ ❤️ pic.twitter.com/8FGLcDSBlJ

— Grace Tame (@TamePunk) September 6, 2021

Recently both Grace Tame and Brittany Higgins have sought to challenge the notion that women who suffer sexual violence should be shamed into silence. They have sought to encourage other women to come forward and speak out. Their advocacy has inspired many including prominent journalist, Lisa Wilkinson, to disclose her experience of being sexually harassed by the father of a friend when she was a teenager.

However, it’s important to recognise that the impact of sexual harassment varies for each affected woman. Some are comfortable in disclosing the experience, others may take years before being able to speak openly about it and for other women the best approach is to leave that experience behind and not revisit it.

To add further complexity, the perspective of many women may change over time. Signing an NDA during a traumatic period of a woman’s life may assist to manage her anxiety and the process or recovering her mental health. Years later, telling her story may become an imperative.

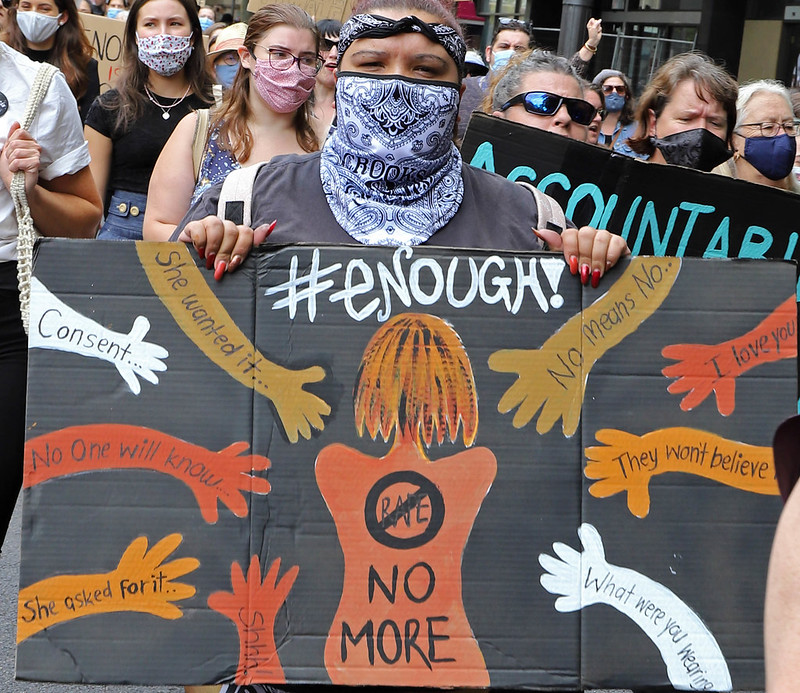

Picture taken at the March4Justice in Canberra. Picture: Kat Berney

Women who complain about sexual harassment are whistleblowers; disturbing the prevailing workplace culture. Like other whistleblowers, they are keenly aware that if they are publicly identified, they may face difficulties in securing employment in the future.

The story of whistleblowers in this country is not a happy one. When former Prime Minister Tony Abbott was recently fined for not complying with health laws requiring the wearing of a mask , he complained that to “dob people in” was not part of the Australian character. That sentiment underpins the experience of many whistleblowers.

A ban on NDAs would rob women of choice.

There is no reason why NDAs could not be adapted to prioritise the interests of women in cases of sexual harassment. Under such an approach, the woman’s identity could be protected for as long as she wished, but could allow the organisation to acknowledge what had occurred including identifying the perpetrator where allegations are substantiated.

- Feature image taken by Jenny Scott at the March4Justice, Tarntanyangga, 15 March 2021. It’s used here under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Josh Bornstein is National Head of Employment Law at Maurice Blackburn and an advisory board member of the Centre for Employment and Labour Relations Law at the University of Melbourne. He is also a writer. Twitter @joshbbornstein