As we move out of the crisis phase of the COVID pandemic, tensions rise over the termination of the Federal Government’s $259 billion stimulus package. The announcement on 22 May of a massive budgeting error in the allocation for JobKeeper sparked immediate conflict over whether the $60 billion ‘saved’ should be spent in other areas of urgent need, or whether it should be clawed back.

The message from the government was unequivocal: the primary consideration was reducing the burden of debt incurred through an unprecedented level of government expenditure.

“At some point you’ve got to get your economy out of ICU,” Prime Minister Scott Morrison told the National Press Club. “We must not borrow from future generations what we cannot return to them.”

‘We have to get the economy out of ICU’: Greg Hunt, Scott Morrison, Josh Frydenberg

Curiously, there were no questions about these assertions. In what sense are we “borrowing” from future generations? Who are we in debt to? Perhaps the distinguished members of the National Press Club are concerned about risking their reputations with such crass questions.

Meanwhile, trillions of dollars are being pumped into global financial markets by the US Federal Reserve. That, too, is ‘stimulus’. Is it also ‘debt’? Or is it just one system pumping money into another system which at some stage, perhaps, will start pumping it back (or perhaps not)? As for the amounts of ‘credit’ and ‘debt’ involved, who’s counting?

These are not crass questions, nor are they academic questions. They are urgent, and immediately relevant to the prospects of Australian citizens at this time. That is why I decided to seek some answers, and will be devoting an upcoming suite of posts in BroadAgenda to the explanations offered by some leading female economists.

I was struck by the fact that so many of the most cogent voices calling for fundamental economic transformation are those of women.

It’s not that I set out to consult their work because they were women, but the more I looked into it, the more I was struck by the fact that so many of the most cogent voices calling for fundamental economic transformation are those of women. I don’t have any formal economic education myself, so I offer these accounts just as a concerned citizen who has made a determined attempt to understand.

British economist Ann Pettifor describes herself as “the little girl who stood in the crowd when the economics emperor walked past, and said he has no clothes”. She has dedicated herself to raising the level of public understanding in an area where too many so-called experts have a vested interest in keeping us ignorant.

I especially want women to do this stuff, because women are very smart, and manage everybody’s budgets except the nation’s.

“The challenge is for us to get ourselves in power and understand how the system works,” she says. “That’s my mission. And I especially want women to do this stuff, because women are very smart, and manage everybody’s budgets except the nation’s.”

Economist Ann Pettifor

Pettifor is one of the architects of the Green New Deal, a policy platform adopted by Bernie Sanders in the US, based on a convergence of environment, economic and social objectives. Her book, The Case for the Green New Deal, explaining the transformative potential of this approach came out last year. But if you want to understand government debt, you need to read The Production of Money (2017), which offers a through, systematic and lucid explanation of the workings of the monetary system, something few economics graduates understand, as she is keen to point out.

Pettifor is a life-long campaigner, who came to prominence 20 years ago as co-founder of the Jubilee 2000 campaign to get $350 billion of debt written-off for 30 of the poorest countries in the world. She was instrumental in getting cancellation of over $100 billion for 18 African countries, from leading global financial organisations including the World Bank, the IMF and the African Development Bank.

Having been brought up in South Africa, lived in Malawi and spent three years at the New Economics Foundation studying the structure and conditions of sovereign debt, Pettifor began to realise she understood things that most academic economists did not. Her research showed that it wasn’t only the poorer countries that had a debt problem. Looking at the figures, she could see that Anglo-American debt was in the trillions and at critical levels relative to GDP.

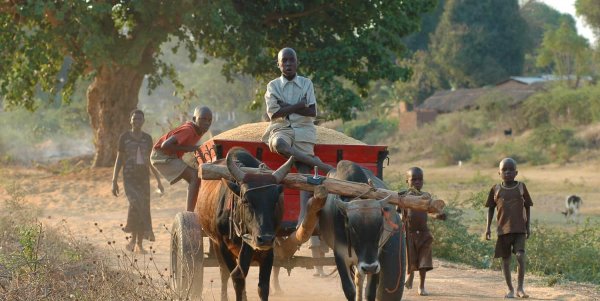

Living in Malawi was formative to Pettifor’s world view.

With the publication of her book The Coming First World Debt Crisis in 2006, she pre-empted all the establishment economic analysts, who began scrabbling to display the wisdom of hindsight when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) manifested itself over the following two years. Through the past decade, she has been predicting another crisis. And with the global economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems it has arrived.

If we are not just to see a repeat of the fallout from the GFC, which allowed banks and other financial corporations deemed “too big to fail” to go free of obligation after receiving massive government bailouts, while ordinary citizens lost their homes and their livelihoods, we – the people – need to be alert to what kind of game we are involved in.

Why is our government so determined to scare us with the spectre of national debt, when it is happy for individuals to “borrow” from their own superannuation accounts?

Why is our government so determined to scare us with the spectre of national debt, when it is happy for individuals and households to “borrow” from their own superannuation accounts, or store up debt for themselves through loan schemes?

Pettifor sets out to explain the workings of monetary policy so that we are better placed to demand a reversal of this priority.

She argues that a sound monetary system – one that is founded on a properly administered taxation process, backed by a strong legislative framework, and has control over its own currency – is a public good. She cites Malawi as an example of a country that does not have these fundamental advantages, and therefore must become indebted to foreign agencies to cover its immediate fiscal needs.

National debt does not mean the same thing in Australia as Malawi.

National debt does not mean the same thing for Australia as it does for Malawi, or for Greece, which was subject to a compulsory bailout loan from the European Union on terms that delivered the most severe austerity conditions for its citizens.

In Australia we have a monetary system that is administered as a public good, by the Reserve Bank. Its charter decrees “that the monetary and banking policy of the bank is directed to the greatest advantage of the people of Australia”. This means, explicitly, ensuring “the stability of the currency, the maintenance of full employment and the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia”.

Interest rates are a crucial factor in any kind of loan system, and as the Reserve Bank has kept ours low, the government is in a sound position to extend its credit, whereas individual citizens or small businesses are much more vulnerable to the profiteering operations of commercial lenders.

The economy serves the people, not the other way about. So how do we pay for this stimulus package?

The economy serves the people, not the other way about. So how do we pay for this stimulus package, with its JobKeeper scheme, its JobSeeker top-up, and all the other citizen-friendly measures it contains? The technical answer is that the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) is raising money through the sale of government bonds to the tune of some $5 billion a week. Since they are backed by all the assets of a working nation, with all its productivity and resources, and its effective taxation system, these are a good investment and there’s no shortage of buyers.

Such government-backed bonds are, says Pettifor, the safest asset in the world. As she points out, there’s a new tax payer born every minute. These new-born tax payers, the ones our government sees as the debt-bearers of the future, will only be burdened with a dismal legacy if we fail to pass on to them a thriving economy, in which the vast majority of people are able to work and spend, to invest in education and health, in ecological restoration and civic amenities.

The debt of a nation like ours is not some nightmare spectre clothed in guilt and shame, threatening to grow to overwhelming proportions. It is a tool to work with, a means of leveraging our own future as a people, with all our diverse needs and capacities. We can control it, if we do not let the threat of it control us.