When it comes to remembering the roles Australians have played in various wars, governments have indulged in a “memory orgy” for the past decade.

After splurging $500 million to honour “100 Years of ANZAC” and $100m to establish the Sir John Monash Centre in France, the government looks set to allocate another $500m, to the Australian War Memorial (AWM) to expand its collection.

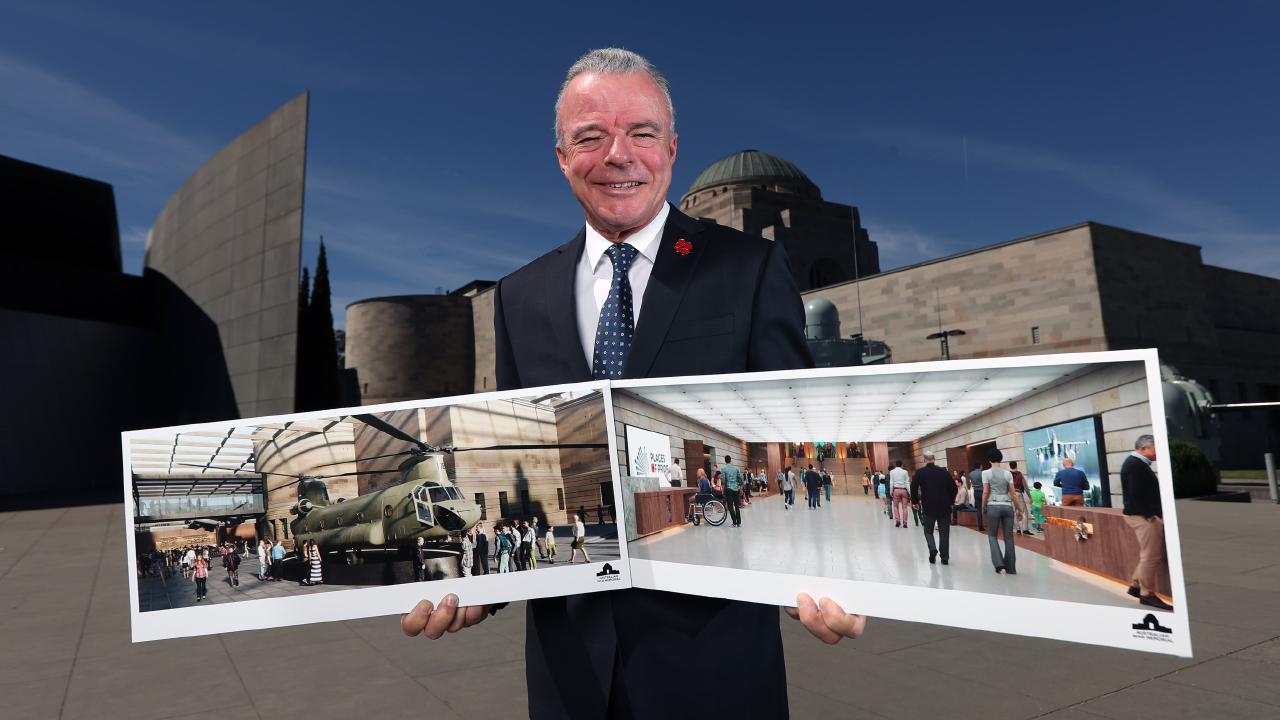

The project, which entails demolishing and rebuilding the award-winning Anzac Hall and creating an area for objects such as fighter planes, helicopters and armoured vehicles in order to “better tell the story of modern conflict”, was formally announced at Parliament House in November 2018.

Former AWM director Brendon Kelson described the project as “toys for the boys.”

Then AWM director Dr Brendan Nelson claimed the building was the “national institution in this country that reveals more than anything else about our character as a people, our soul.” Prime Minister Scott Morrison said the project would allow the AWM to “adjust to new times so it can continue delivering as a place of commemoration and understanding as the soul of the nation.” By contrast, former AWM director Brendon Kelson described the project as “toys for the boys.”

The architecturally significant Anzac Hall is set to be demolished.

As part of ongoing public consultation, the scheme was referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works on 30 April, with people and organisations able to lodge submissions until 17 July.

On behalf of the group, Heritage Guardians, a non-profit group that includes two former directors of the AWM, Dr David Stephens told the Committee the plan had been “slipshod and arrogant”. In an independent submission, former AWM director Steve Gower said the proposal was “an emotional and jingoistic misrepresentation to justify huge sums of money.”

Others critics saw the project as a type of “giantism” and akin to “vandalism”. According to Paul Barratt, former secretary of the Department of Defence, the AWM risked being turned into “a sort of military theme park.” Professor Peter Stanley, former head of Historical Research Section and Principal Historian at the AWM said claims that military aircraft and vehicles would help veterans to heal their trauma was “the hydroxychloroquine of the museum world.”

This profligate project comes at a time when the government has slashed the budgets of other national institutions … and is MIA when it comes to a national cultural policy.

This profligate project comes at a time when the government has slashed the budgets of other national institutions, such as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, National Gallery of Australia and National Film and Sound Archive, and is MIA when it comes to a national cultural policy.

The government also has incurred a massive debt dealing with coronavirus that will keep escalating and take decades to pay off. Meanwhile, medical and political leaders repeatedly remind Australians they need to make sacrifices because “We’re all in this together.

The politics of war memory and commemoration

National memorials and museums are inherently contested terrain, because they are established by government edicts that reinforce mainly conservative values. This “politics of war, memory and commemoration” is evident in museums of white settler nations that have been criticised for privileging white patriarchal values.

Spending billions on war commemorations is one example of how authoritarian governments have responded to challenges from “modernist and progressive narratives.” This typically involves populist “strongmen” invoking regressive, masculinist nationalist pasts to bolster their declining authority, and fomenting moral panics about political correctness, cancel cultures and identity politics.

John Howard’s view of Australia put ANZACs and mateship front and centre.

John Howard orchestrated a variation of authoritarian-populism during his four consecutive terms as Prime Minister. This was a double movement of advancing an Anglophilic and masculine version of Australia, with the Anzacs and “mateship” front and centre, and accusing his critics of promoting “black armband” and “unAustralian” views of history.

Howard’s chief protégé, Tony Abbott, a member of the AWM Council, is a prominent “ANZAC birther”.

Howard’s chief protégé, Tony Abbott, a member of the AWM Council, is a prominent “ANZAC birther”. When Abbott was Prime Minster he claimed “The Gallipoli landing was in an important sense the birth of our nation. Certainly it was the coming of age.”

This deeply white, masculinist nationalism means it has been a long, slow process to have the contributions of servicewomen and nurses recognised. Similarly, acknowledgement of service by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is a recent development, and the AWM refuses to officially recognise the Frontier Wars.

Organised irresponsibility

In principle, we believe in commemoration and the appropriate honouring of military valour, However, in this instance, the improvident transmogrification of the AWM from a national into a nationalistic institution replete with “toys for boys” is a textbook example of “organised irresponsibility”. In these situations bureaucrats make minor concessions but “carry on regardless” without being accountable for their actions.

The Council does not even have a professional historian. Nelson was granted approval for every phase of his proposal, and the enlargement was supported by both major political parties.

AWM chair Kerry Stokes with Brendan Nelson.

Former army officer and AWM director, Matt Anderson, AWM Council chair, Kerry Stokes, and Nelson have staunchly repudiated criticisms. Nelson said critics were inclined “to have a fixed narrative about the Memorial, which was unlike any other cultural institution”(emphasis added). Given this structure of power, the AWM is likely to “carry on” with its empire-building.

AWM volunteers were even warned they could lose their positions if they commented publicly about the expansion.

The government’s indulgence of the AWM’s claims for special treatment on the basis Anzac is sacrosanct, and white male fantasies about the site being the nation’s “soul” does not augur well for diversity. AWM volunteers were even warned they could lose their positions if they commented publicly about the expansion.

The AWM resembles the scenario described by intelligence officer Major Cate Carter of trying to attract more women into the armed forces. She describes it as “pragmatic” rather than “ideological” inclusion. Consequently, diversity in representation does not equate to diversity in thought, and is therefore unlikely to achieve meaningful difference.

Likewise, in supporting the “upgrade” to the AWM the government yet again reveals its complicity in privileging white men and marginalising issues of race, class and gender in Australia. This highly selective nationalist narrative gratifies its advocates’ politics (and egos) rather than adding significant social value – not only at the expense of diversity, but of other worthy national institutions.