According to tradition, leap years are a boon for women’s empowerment. When February 29 pops up on our calendars, cultural traditions surrounding marriage give permission for a woman to propose marriage to her partner, flipping the societal convention.

Of course there’s nothing preventing a woman from proposing any time she wishes. But these traditions tell us something about the ‘acceptable’ roles of men and women in society.

The fact that this role reversal occurs only every four years – and only due to a quirk in the calendar – reflects the reality that giving women an equal role to men in society is still considered an anomaly.

What do Australians think about gender equality?

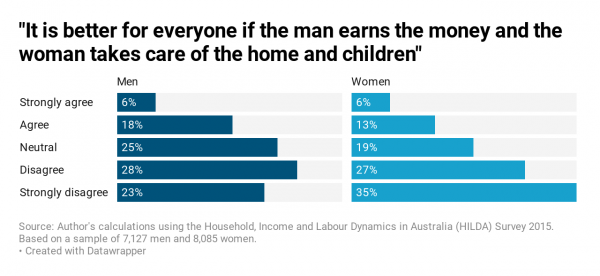

We can gather a picture of Australians’ attitudes on gender roles from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey.

In the context of heterosexual relationships, most Australians express support for men and women having equal roles in the household and society. But far from all.

One in five Australians believes that the traditional model of the male breadwinner and the female caregiver works best. In the HILDA Survey, this is measured by asking participants how strongly they agree that “it is better for everyone if the man earns the money and the woman takes care of the home and children”. Men tend to support the breadwinner model more than women – 24% either agree or strongly agree compared to 19% of women.

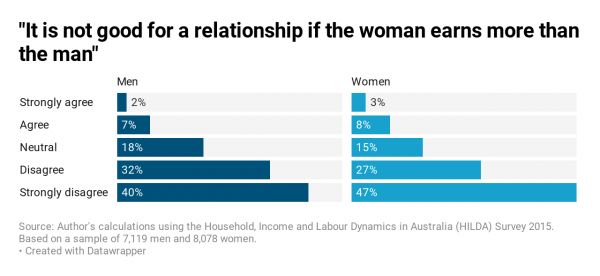

Even if a woman steps into the workforce, one in 10 people caution that she shouldn’t bring home a larger pay packet than her male partner. This is captured by the HILDA Survey statement “it is not good for a relationship if the woman earns more than the man”. Fractionally more women believe this – 11% compared to 9%.

We need to be mindful that the survey questions do not necessarily capture a person’s belief about how things should be. Rather, it can reflect their assessment of how things are. And a person’s view about what relationship arrangements ‘work best’ is likely to reflect their own life experiences.

We need to be mindful that the survey questions do not necessarily capture a person’s belief about how things should be. Rather, it can reflect their assessment of how things are. And a person’s view about what relationship arrangements ‘work best’ is likely to reflect their own life experiences.

There are also clues that some women may have stepped away from paid work because their economic empowerment created tension in their relationships. A larger fraction of non-working women, compared to working women, believe that high female earnings puts a relationship under strain – 10% compared to 6%. Worryingly, this implies that a woman’s right to economic empowerment can be undone by traditional societal norms.

Why do these attitudes matter?

Parents with traditional attitudes might be less likely to encourage their daughters’ pursuit of education and career, especially in traditionally male fields such as science or engineering.

Men with traditional attitudes might suppress their female partner’s capacity to independently earn her own income and advance her career.

Traditionally-minded managers might be unconsciously biased in their hiring and promotion decisions. Indeed, the survey finds that 16% of managers endorse the breadwinner model.

Traditionally-minded managers might be unconsciously biased in their hiring and promotion decisions.

All these factors perpetuate the over-representation of men in decision-making roles and in the highest-earning jobs.

The breadwinner norm is also damaging for men, pushing them into hyper-competitive work practices, forgoing time with family at home, and battling mental and emotional distress when they fall short of masculinised stereotypes.

These attitudes matter for women’s health, safety and wellbeing. Beliefs that women are best suited to domestic roles, and that men are best suited to positions of power, contribute to an environment where violence against women and children is more likely to occur.

Are attitudes changing with younger generations?

Among people aged 60 years and older, support for the breadwinner model climbs to almost 40 per cent. These numbers make it tempting to assume this story will be fixed by generational change.

But older Australians’ traditional attitudes are not necessarily just a sign of the times. It’s possible that some older people once held the pro-equality beliefs displayed by the youth of today – but life taught them that such beliefs do not work in reality.

It’s possible that some older people once held the pro-equality beliefs displayed by the youth of today – but life taught them that such beliefs do not work in reality.

The HILDA Survey allows us to trace people’s responses over time to see if their attitudes change. We find that attitudes can slide along this spectrum, in both directions.

Over a 10-year window between 2005-15, two-thirds of people in the survey maintained their initial view. Around 20% shifted towards a more pro-equality attitude. While a larger number of men than women changed in this way, more women were pro-equality to begin with.

The remaining 16% of the survey slid the other way towards a more traditional view. This change of mind mainly related to the issue of women out-earning men.

Following Finland?

In attempt to dismantle the breadwinner norm, Finland has announced that equal amounts of parental leave will be available to both mothers and fathers.

Would this work in Australia? While a small fraction of Australian dads are taking parental leave, or stepping into the full-time caregiver role while mum returns to work, many men struggle to let go of the breadwinner role or suffer stigma if they do.

As women already know, breaking free of societal norms is tough. Modernising policies to dismantle gender stereotypes is a start. But we need to be aware of the forces we’re up against.

When February 29 comes around, it’s an opportunity to re-evaluate our default settings and interrogate the gender norms we unthinkingly ascribe to. And then 2020 will be a leap forward for gender equality.

Dr Leonora Risse is an economist who specialises in gender equality. She is an Associate Professor at the University of Canberra and a Research Fellow with the Women’s Leadership Institute Australia. Dr Risse engages regularly with governments and organisations on evidence-based strategies to close gender gaps and how to apply a “gender lens” to economic analysis and policy design.