October 2020 will mark the 20thanniversary of the United Nation Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325). Together with nine subsequent resolutions on Women, Peace and Security, two of which were adopted earlier this year amidst some controversies, UNSCR 1325 advocates for gender equality in all aspects of peace and security. It is timely to reflect upon what has or has not been achieved over the past two decades, both globally and in Australia.

The Women Peace and Security (WPS) Index is one tool to gauge progress on UNSCR 1325. Produced by Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) and Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), the WPS Index is a composite measure of women’s wellbeing. Deriving from global priorities laid out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, it is an important step to bridge the systematic silos between security and development.

Last month we saw the second edition of this biennial initiative. The WPS Index ranked 167 countries across three dimensions that were deemed most relevant to women’s wellbeing: inclusion (economic, social, political), justice (formal laws and informal discrimination) and security (at the family, community and the societal levels). These three dimensions were weighed equally and quantified according to 11 subindexes, relying on publicly available data from the International Labour Organisation, the United Nations, the World Bank, the Inter-Parliamentary Union, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program and other recognised sources.

Overall, the WPS Index suggests that there are reasons for optimism with some 59 countries recording significant progress since 2017. Australia is not among them.

Overall, the WPS Index suggests that there are reasons for optimism with some 59 countries recording significant progress since 2017. Australia is not among them. This year Australia ranked 22nd, compared to the 17thplace in 2017.

Does this mean that women’s wellbeing deteriorated in Australia, according to the WPS Index?

No. The overall score is higher this year (0.844 compared to 0.827, where 1 is the best possible score and 0 the worst) and the authors of the WPS Index caution against drawing direct comparisons of ranks between 2017 and 2019, due to improvements of data and the inclusion of 14 new countries. As a matter of fact, Australia advanced slightly across six subindexes for which comparable data is available for both 2019 and 2017.

But does this mean that Australia is not progressing fast enough or even that the progress has stagnated?

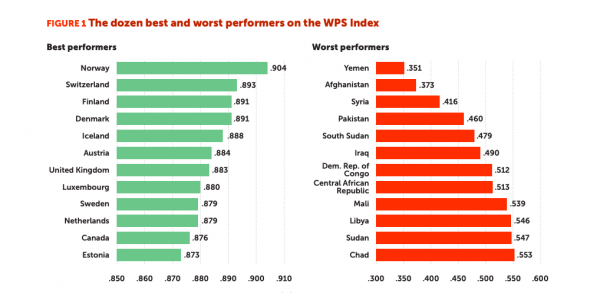

Possibly. Not making into the top 20, Australia lagged behind countries with similar policy contexts. The UK ranked 7th, Canada 11th, New Zealand 14th and the US 19th respectively.

2019 worst and best performers. Source: WPS Index 2019-20 report

Australia achieved rather average results amongst countries in the same category in relation to some of the key subindexes. For example, the percentage of women ages 25 and older who are employed was 56 (compared to 68.6 in Iceland) and women’s share of parliament seats amounted to 33.2 percent (compared to 47.3 percent in Sweden).

Yet, one subindex – community safety – is to blame for Australia’s mediocre score overall. This measures the percentage of women ages 15 years and older who report that they feel safe walking home at night in the city or area where they live. Australia’s outcome is disturbingly low at 49.6 percent. Put simply, one in every two women does not feel safe. With this result, Australia scored way below the global average of 63.8 percent.

The major shortcoming of the WPS Index is the lack of any measure on the involvement of civil society; whether in the national implementation of UNSCR 1325 or more broadly in national governance

The WPS Index is just one tool to monitor progress on UNSCR 1325. While relatively comprehensive, the major shortcoming of the WPS Index is the lack of any measure on the involvement of civil society; whether in the national implementation of UNSCR 1325 or more broadly in national governance. Civil society has been absolutely crucial to the realisation of UNSCR 1325’s goals, a resolution that was initiated by advocacy and activism of women’s organisations and networks.

One in every two women does not feel safe walk home at night in Australia

CIVICUS has monitored the state of civil society globally since 2012. Sadly, the most recent data is not optimistic for Australia either, suggesting that civic space in Australia is narrowed.

The Australian National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security completed earlier this year predominantly engaged with the issues of gender equality in foreign and security policy, development and aid program and diplomacy, as opposed to tackling internal challenges. Both the unimpressive ranking in the WPS Index and the data from CIVICUS suggest that it is high time to look inwards – in addition to outwards – and address obstacles to the wellbeing of women in Australia.