As I usually do on a Sunday morning, I sat down to watch Insiders. I was expecting to hear the nation’s top journalists mull over the week’s much-discussed gender politics issue concerning sexual assault allegations made by women staffers of the Liberal Party. I wasn’t expecting to be left physically ill by an exchange between two women parliamentarians in the Tasmanian House of Assembly.

[Ms O’Byrne interjecting]

Madam Speaker: Miss O’Byrne, it’s very un-ladylike to be yelling in the Parliament …

[…]

Ms O’Byrne: Can I draw your attention to the inappropriateness of mentioning someone’s gender in any kind of warning in Parliament. If you wish to refer to me, my name is Michelle O’Byrne, or the Member for Bass or the Deputy Leader of the Opposition.

Madam Speaker: Sorry Miss O’Byrne, are you referring that to me?

Ms O’Byrne: Yes, Madam Speaker: the word ‘ladylike’, Madam Speaker.

Madam Speaker: [Rising in her chair.] Oh for goodness sake. This is political correctness taken to the nth degree. Your behaviour was inappropriate, whether it was ladylike or otherwise, and I will not be spoken to like that again, Miss O’Byrne.

House of Assembly, Parliament of Tasmania (as shown on the ABC’s Insiders program, 4 August 2019)

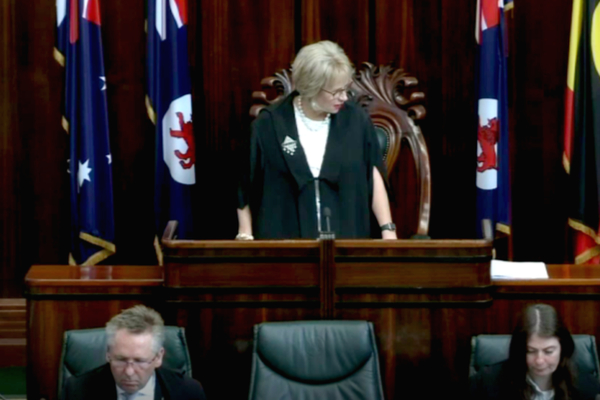

Tasmanian Speaker Sue Hickey doesn’t believe her comment on ‘ladylike’ behaviour was offensive.

A couple of things troubled me about this exchange. The first was the contestation over women’s titles, and in particular, Madam Speaker’s repeated and deliberate references to Ms O’Byrne as “Miss”. Feminists, a title which Ms O’Byrne clearly applies to herself, deliberately appropriated the title “Ms” to avoid the diminutive connotations associated with “Miss” in the 1970s, and the term has enjoyed social legitimacy for at least the last decade if not longer.

This is not just petty semantics, or the mere contestation over the meaning of a word: it encapsulates a political difference on the nature of women’s identity

This is not just petty semantics, or the mere contestation over the meaning of a word: it encapsulates a political difference on the nature of women’s identity. This debate is often played out between those who wish women to be defined by their marital status, and those who wish to apply the same set of rules to men and women. If “Mr” can be used for both married and unmarried men, then surely a similar principle should apply to women? Not to mention the fact that when we use the term “Ms”, we abide by the (Commonwealth) Sex Discrimination Act 1984 that outlawed discriminatory treatment of women on the basis of their marital or relationship status.

But surely, in the 2010s, a woman’s title should no longer be a matter of debate. The decision ought to rest with each individual woman, and once announced officially (as it is on the Tasmanian Parliament’s website), it should be accepted. Madam Speaker has chosen her title, as has Ms O’Byrne. They each deserve the respect that comes from society’s endorsement of those decisions.

Increasing the number of women elected to politics would be one way to begin to rectify the problem, but it’s more than a question of numbers. We need to recognise the gendered expectations of how men and women interact in parliament and in parliamentary debate

The second concern is with what feminists call the ‘gendered nature of parliamentary norms’. For decades, feminist researchers have been documenting the very masculine way politics is conducted in parliaments across the globe. If historically, men defined the rules of the game – and still predominantly play the game, then they clearly have a natural advantage in continuing to set the standards of play, or the ‘norms of behaviour’. Sure, increasing the number of women elected to politics would be one way to begin to rectify the problem, but it’s more than a question of numbers. We need to recognise the gendered expectations of how men and women interact in parliament and in parliamentary debate.

There is often an assumption that parliamentary norms are ‘ungendered’ or ‘gender-neutral’. Yet these expectations are gendered when we judge women politicians more harshly than their male counterparts for the same act, or when we apply one set of rules to men and a different set of rules to women, as was the case in Tasmania. Madam Speaker has consciously – or unconsciously – determined that Ms O’Byrne’s behaviour was inappropriate because it was “un-ladylike”. While Madam Speaker has only held this office for just over a year, the term ladylike is not found in any other context in the Tasmanian Parliament’s Hansard.

The real problem here isn’t that there is a difference of expectation – it’s that the expectation for women is completely antithetical to conceptualisations of masculine parliamentary behaviour. Ms O’Byrne was asked to conform to a yardstick that would never apply to men, or our ‘ideal parliamentarian’.

Yes, it is the Speaker’s role to restrain “unruly or unparliamentary behaviour”, and if she determined Ms O’Byrne’s interjections to fit under this category, she was well within her right to call Ms O’Byrne to order.

Parliament of Tasmania

The Speaker, however, also has an obligation under the Standing Orders to act “in an impartial and non-partisan manner”. There is perhaps something unspoken about the way in which party politics does define this debate: some (but certainly not all) conservative women have shown less sympathy for the politics of identity. By defining the exchange as “political correctness to the n’th degree”, she reveals her disdain for a call for more tempered language.

The partisanship of this exchange is also made more obvious because it is between two women. I have found myself wondering what the tenor of the exchange would have been if the Speaker had been male. Would he have been as offended? Would he have realised his mistake? In this #MeToo moment, would he have apologised?

If parliaments are to become gender-sensitive, we need to acknowledge that there are often gendered double standards, and that in rectifying those double standards, our allies might be men.