From its confronting title through to its horrifying conclusion, Listen, bitch (Recent Work Press, October 2019) takes no prisoners in its critique of misogynistic language and violence against women. Composed by two Canberrans – poet Melinda Smith and artist Caren Florance, the poetry collection seeks to highlight the ongoing dehumanisation and degradation of women in Australia, as well as worldwide.

Yet stylistically, this is no ordinary book of poetry. It is a collection of found poetry, made by working primarily with several decades’ worth of misogynistic statements made by major Australian public figures.

Found poems are a form of poetry where words and phrases from other sources are reframed – sort of like the literary equivalent of a collage – in order to elicit or impart new meaning from these words.

In the case of Listen, bitch, one has the impression many of those quoted in the book’s poems would rather their statements were forgiven, forgotten, or swept under the carpet

In the case of Listen, bitch, one has the impression many of those quoted in the book would rather their statements were forgiven, forgotten, or swept under the carpet. In creating this collection, however, Smith and Florance refuse to let these statements be buried; instead, they are brought out into the light and interrogated.

The following excerpt demonstrates the nature and power of these poems.

It’s very unladylike to be yelling in the Parliament

Constant male bashing It’s not

in our values I’m a country guy so I know

Why would I vote for Malcolm in a skirt?

It’s not in our values to push some people down

to lift some people up. That is how

To fly a plane, ride a horse, and

That is true of gender equality

We don’t want to see women rise

Excerpt from ‘Zero Sum’ in Listen, bitch (p.7).

In three short stanzas, Smith manages to splice quotes from politician Sue Hickey, media commentator and sex therapist Bettina Arndt, Prime Minister Scott Morrison, former politician Andrew Broad, and former Prime Minister Tony Abbott. Yet their richness in embedded textual references is hardly unique within this collection.

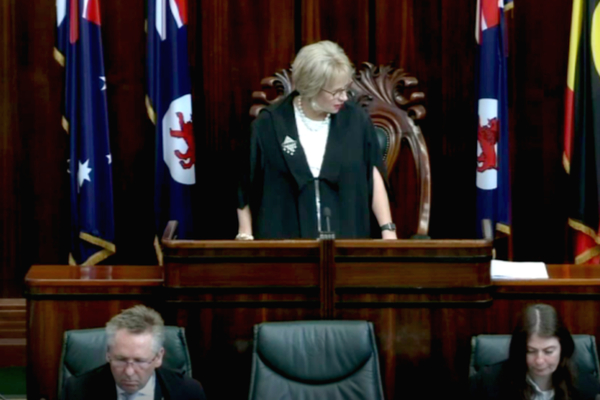

Tasmanian Speaker Sue Hickey called for ‘ladylike’ behaviour in the Parliament, and subsequently refused to acknowledge the offensive nature of her comments.

Each poem in the book is extensively footnoted, providing sources for exact quotes as well as descriptions of the contexts in which they were said. As found poetry goes, these lines are illuminating as well as damning – and they offer powerful evidence of the fact sexism and misogyny are far from dead in Australia, not least among those with the largest megaphones and platforms within our society.

Of course, the irony is that many of those quoted in Listen, bitch would neither read nor feel chastened by this book. Language and tone are typically subjective enough that a speaker’s intent can be difficult to pin down, meaning words that offend often incur only minimal – certainly not lasting – repercussions.

Misogynistic language hits our airwaves on a regular basis, but rarely does it result in sexist broadcasters losing their platforms permanently

For example, in Australia, a man can celebrate International Women’s Day with the words “we don’t want to see women rise only on the basis of others doing worse” and only be met with minor uproar. A man can also campaign hard to drag the personal into the political arena by pushing for a plebiscite on marriage equality, then turn around and advocate for the separation of public and private when it comes to his sex scandal. Misogynistic language hits our airwaves on a regular basis, but rarely does it result in sexist broadcasters losing their platforms permanently.

Listen, bitch may end up being read primarily by an audience already aware of the violent language used to describe and address women – an audience needing no convincing of how violent language can help enable violent acts. Nevertheless, this book also has the potential to be picked up by an unsuspecting reader drawn to its punchy title, who will then be confronted with a small sample of the misogyny that has been directed towards women in Australia for decades. If this scenario occurs even just once, republishing the vitriol contained in the book’s pages will have been entirely worth it.

Listen, bitch may end up being read primarily by an audience already aware of the violent language used to describe and address women – an audience needing no convincing of how violent language can help enable violent acts. Nevertheless, this book also has the potential to be picked up by an unsuspecting reader drawn to its punchy title, who will then be confronted with a small sample of the misogyny that has been directed towards women in Australia for decades. If this scenario occurs even just once, republishing the vitriol contained in the book’s pages will have been entirely worth it.

What’s more, this book has significant potential to be discussed further in political as well as poetry circles. Listen, bitch is born of this city, not only because Canberra is home to the book’s creators, but also because its highly politicised cultural milieu is what led to some of the book’s most striking quotes.

Canberra is a juxtaposition; one where myriad public servants are increasingly discouraged from articulating their views, while many politicians cultivate increasingly divisive politics and personas. This phenomenon is also evident on a global scale, such as in the (somewhat) United States and the (even less) United Kingdom. As a book that highlights the dangers that come of divisive, misogynistic language, therefore, Listen, bitch is truly a book for our times.

Ultimately, much like some of our most influential and game-changing women, this book rightly refuses to be quiet

Ultimately, much like some of our most influential and game-changing women, this book rightly refuses to be quiet. Through providing a second, more critical platform for statements that were aired publicly and then allowed to slip under the radar, it seeks to redress some of the indignities and cruelties directed towards women in Australian society.

It also draws a direct line between linguistic ignominies and violence and harassment directed towards women, such as in the case of the rape and murder of Eurydice Dixon. Indeed, the argument underpinning the book is that violence against women is allowed to continue as a result of our society tolerating misogynistic language – something we have tolerated for far too long already.

Clean out your ears, kindly citizens (female and otherwise). The message of Listen, bitch deserves to be heard.