Overview of the region

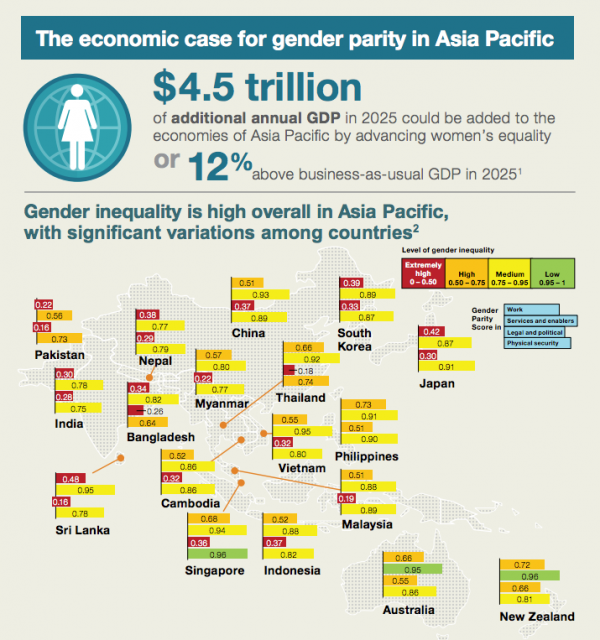

All countries would benefit from advancing women’s equality. In a best-in-region scenario in which each country matches the rate of progress of the fastest-improving country in its region, the largest absolute GDP opportunity is in China at $2.6 trillion, a 13 percent increase over business-as-usual GDP. The largest relative GDP opportunity is in India, which could achieve an 18 percent increase over business-as-usual GDP, or $770 billion.

Mckinsey Global Institute has established a strong link between gender equality in work and in society—the former is not achievable without the latter. But countries in the region vary in their positions on specific indicators. There is no single Asia Pacific story.

On gender equality in work, the Philippines stands out for its progress, followed by New Zealand and Singapore. The six countries furthest from gender parity in work are Bangladesh, India, Japan, Nepal, Pakistan, and South Korea. China does well on female labour-force participation but can improve its share of women in leadership—as can most countries in Asia.

On gender equality in society, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Singapore are ahead of most in the region on essential services such as education, maternal and reproductive health, financial and digital inclusion, and legal protection and political voice; countries like Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan still have a considerable distance to travel.

How is Australia tracking?

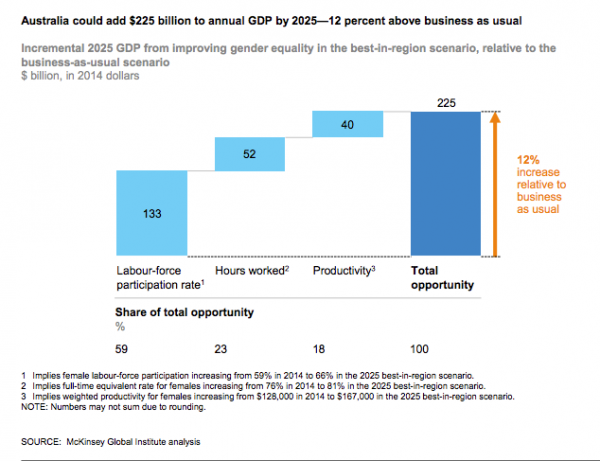

Australia could add $225 billion or 12 percent to annual GDP by 2025 in a best-in-region scenario by accelerating progress towards gender parity. Increasing women’s participation in the labour force accounts for 59 percent of the GDP potential, 23 percent comes from increasing the paid hours women work, and 18 percent derives from increasing their productivity by equipping them to participate in higher-productivity sectors.

(Getty Image: McKinsey report)

(Getty Image: McKinsey report)

Women currently make up 46 percent of Australia’s labour force while accounting for 36 percent of the nation’s GDP. This matches the global average but falls considerably behind Singapore, Canada, and the United States, where women contribute 39 to 40 percent, and France, where the share is 43 percent.

Australia is relatively advanced on closing gender gaps compared with other countries in Asia Pacific, but the gap with world leaders on gender diversity is widening. The country has an opportunity to accelerate progress and become one of the world’s leaders on gender inequality, particularly on female labour-force participation.

Australia has travelled further towards gender parity than others in the region and has scope to do even better

Australia is further advanced towards parity than the Asia Pacific average on gender equality in work and on all three elements of gender equality in society. In fact, it has made more progress than the regional average on all 15 gender inequality indicators. It is near best in region on female-to-male ratio in professional and technical jobs, maternal mortality, sex ratio at birth, and child marriage, and best in region on educational level and financial and digital inclusion. In education, women have been participating in tertiary education at higher rates than men for decades, and they overtook men in enrolment in post-graduate degree programmes in 2006.

Progress has stagnated in recent years on key indicators such as gender wage gaps and women’s political representation.

Nevertheless, inequality on political representation is still a major issue, and rates of violence against women remain high. Progress has stagnated in recent years on key indicators such as gender wage gaps and women’s political representation. The full-time gender pay gap was 16 percent in 2017, only one percentage point lower than in 1996.

…that rise is still more modest than in other nations, leading to a drop in Australia’s ranking

Representation of women in Australian parliaments increased from 21 percent in 1997 to 33 percent in 2017, but that rise is still more modest than in other nations, leading to a drop in Australia’s ranking on this metric by the Inter-Parliamentary Union from 27th to 50th.

Australia can now aspire to be a world leader on all these aspects of gender equality, but it is not there yet. Of particular importance, given that it is a major source of additional GDP growth, is boosting women’s participation in labour markets. Australia lags slightly behind some other advanced economies with a female-to-male labour-participation ratio of 0.83, compared with the United Kingdom and New Zealand at 0.88, Canada at 0.91, and the Nordic states, led by Sweden at 0.96. Australia has made some progress. Its participation ratio rose from 0.76 to 0.86 between 1995 and 2015, slightly faster progress than in other developed countries.

Australia also has much higher rates of women working part time than the OECD average. This is both good and bad news

Australia also has much higher rates of women working part time than the OECD average. This is both good and bad news. On the one hand, it suggests Australia may be relatively good at making part-time work possible for those who want it, effectively keeping women connected to the workforce when they don’t want to—or cannot—work full time.

On the other hand, the high rate of part-time work may indicate that women find it relatively hard to transition back into full-time work. Moreover, high rates of female part-time work without equivalent rates of male part-time work may entrench gender roles.

Female labour-force participation is critical to delivering the potential GDP boost from advancing women’s equality

Demographic change means that there is a pressing need to increase the number of Australian workers, and increasing women’s labour-force participation is one way to achieve this.

In order to increase women’s labour-force participation, the key group for Australia to focus on is women aged 24 to 35 who have children

In order to increase women’s labour-force participation, the key group for Australia to focus on is women aged 24 to 35 who have children. They currently drop out of the workforce in great numbers—more than in many other countries. The gap between female and male participation is largest in this age bracket; the female participation rate is around 75 percent, while the male rate is 91 percent. This gap largely arises when women have children and do not subsequently return to the workforce.

There is a 15 percent gap in participation between women without children and mothers. Even when women want to return, many struggle; the gap in underemployment between men and women is largest (at over 5 percent) in the 35-to-49 age bracket. This gap is not inevitable. Australia’s maternal participation rate is lower than the average in advanced OECD economies. Moreover, global evidence suggests that high female labour-force participation is consistent with maintaining high rates of employment for men.

Short-term financial incentives to work limit uptake of formal childcare

Australia has low uptake of paid childcare, creating a gap that is often filled by mothers. In all key age groups, Australian children’s participation in formal childcare is slightly lower than the OECD average and significantly lower than in peers that have adopted best practices. This is due to a combination of high childcare costs and the way the tax system is set up. For many households, there is little economic incentive for second earners (often women) to return to work instead of caring for children at home.

Thirty percent of non-working parents with children from birth to the age of 12, and 49 percent of part-time working parents, say that expensive childcare is the primary barrier to their participation in the labour force. Net childcare costs (the amount paid by individual families) were 20 percent of an average family income in 2015, compared with an average of 13 percent in OECD economies. Net childcare costs have continued to rise substantially faster than household incomes since this comparison was made in 2015.

Government spending per child up to the age of three is slightly lower than the OECD average, but spending on pre-primary education (for children aged three and upwards) is relatively high. The OECD estimates that in 2013 the Australian government spent $13,171 per child on pre-primary education, significantly above the OECD average of $8,070, $8,727 in the United Kingdom, and $10,252 in New Zealand, but below $14,704 in Norway.

Compounding this issue is the way the Australian tax system treats family benefits and childcare rebates, which are means tested on the basis of household income so that the contributions of secondary wage earners are added to those of the primary earner. This is in contrast to income tax that treats each individual in a household separately. This means that there is very little economic value for a parent to return to work as secondary earners, at least in the short term.

Australia’s Productivity Commission estimated that a secondary earner on an average wage would designate more than 50 percent of earnings for childcare if they worked two days per week, and over 90 percent of their earnings if they worked four days per week. From a purely financial perspective, therefore, it often makes more sense for a mother to step out of the labour market to look after children than a father, as his full time salary is on average higher.

Workplaces can help women balance work and family and encourage men to be more active in childcare – but both provision and uptake of support need to rise

Two types of workplace practices are important to enabling women to work—policies that enable flexible work, and programmes that help women during life transitions such as becoming a mother and then returning to work. Provision of such arrangements is only the first step. The second is to encourage their uptake.

In Australia, there is considerable room for both improved provision of workplace policies and higher uptake among men. Only 52 percent of employers have a flexible working arrangement policy, 16 percent have a flexible working strategy, and only 13 percent of companies offer eight or more flexible work options (an indicator of best practices) to both men and women who are both managers and non-managers. It doesn’t need to be this way. Some Australian companies are demonstrating that improving access to flexibility is possible with sufficient creativity and commitment. For example, REA Group enables job sharing by pairing coders who contribute to the same piece of work (even if they work in different offices), an approach that is often considered too logistically difficult.

Specifically on parental leave, Australia’s federal mandate, while not lagging behind global peers, is not consistent with best practices. Australia provides 18 weeks of paid parental leave at minimum wage plus two weeks of minimum-wage “Dad and Partner Pay”. This is much less generous than Germany’s scheme, which provides 14 weeks of maternity leave, paid at 100 percent of the individual’s earnings with no ceiling (mostly covered by employers). In 2012, only 28 percent of Australian employers had employer-paid maternity leave, and only 22 percent had paternity leave.

Moreover, uptake is low among men. Only 24 men per 100 live births take federally provided paternity leave, less than one-third the rate in Finland. Eleven percent of fathers take no time off when their baby is born, and for those who do, the average duration is short. Surveys suggest that the low uptake is related to financial considerations and perceptions in the workplace that men are not carers to nearly the extent that women are.

Shifting attitudes among men and women towards gender roles is necessary to maximise women’s participation

Even if childcare were affordable, the tax system worked in favour of second earners in households, and flexible working policies were to spread, a change in societal attitudes is needed to achieve the full value of women’s participation. While Australia is relatively progressive compared with many other countries on attitudes towards the role of women, there is room for more progress.

Traditional attitudes about the role of women in society persist, and may act as a constraint on many women wanting to participate in paid work. In the World Values Survey, 21 percent of Australians agreed with the statement “When a mother works for pay, the children suffer”. In the 2014 Longitudinal Study of Australian Children survey, 28 percent of mothers and 27 percent of fathers agreed with the statement “It is better for the family if the husband is the principal breadwinner outside the home and the wife has primary responsibility for the home and children”. These attitudes exhibit remarkably little progress over time.

They also flow through to how couples operate at home. Women undertake around two-thirds of the unpaid care work in Australia, even when both members of the couple are employed full time, but still tend to view the division of unpaid labour as “fair”.

Attitudinal shifts are vital to unlocking the full potential of other policies such as those offering flexibility at work

Such attitudes reduce women’s labour-force participation. Women are much more likely to step out of the workforce when they or their partner hold traditional attitudes.

Attitudinal shifts are vital to unlocking the full potential of other policies such as those offering flexibility at work. In 2012, 57 percent of Australians said they believed that paid leave entitlements should be taken entirely or mostly by the mother. This suggests that without shifts in attitudes, women will continue to take on the bulk of leave and flexible work, even when those opportunities are equally available to both genders.

For the full report see McKinsey Global Institute. The Power of Parity: Advancing Women’s Equality in Asia Pacific