‘Crisis of masculinity’ is driving levels of intimate partner and sexual violence in the Western world. Widely held beliefs in sexual differences, which promote the ‘boys will be boys’ position, have been challenged by contemporary research in neuroscience, biochemistry, archaeology and anthropology. The existence of a ‘male code’ – that is, socially approved ways of being male – implicates shame and rage when this code is not lived up to.

How then can a Lacanian interpretation further explain the emotional intensity (or ‘jouissance’ in Lacan’s terminology) experienced by perpetrators? Can it help explain why the occurrence of violence between intimates is so skewed towards men against women? And how can it help prevent such violence in the future?

It achieves this by understanding masculinity and femininity in a way largely independent of biology.

A Lacanian approach to these questions is consistent with the contemporary research describing a more complex and contingent model of developmental pathways and a resulting diversity of sexual identifications and preferences. It achieves this by understanding masculinity and femininity in a way largely independent of biology.

The theory of sexuation

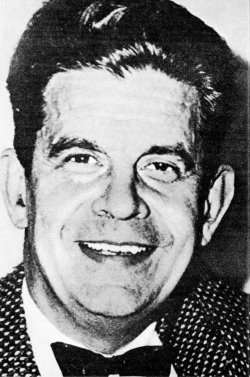

Encyclopédie du Monde Actuel (EDMA); copyright Charles-Henri Favrod

Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) was a controversial French psychoanalyst and teacher who introduced his ideas on masculinity and femininity at a series of seminars in Paris in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Seminars XVIII – XXI). Like Freud, Lacan has been criticised by much feminist scholarship as promoting ‘phallocentric’ power structures.

However, feminist psychoanalyst Elizabeth Wright argues that Lacan’s “theory of sexuation, the origin and development of sexual difference within the field of language” has been largely misinterpreted. According to Wright, the theory provides a necessary “division between organism and subject [that] removes the need to depend on a biological determination of gender, which always assumes a masculinity and femininity derived from the real body”.

For Lacan, every human being has the experience as an infant of, more or less successfully, being inducted into a ‘Symbolic Order’ of social rules, laws, categories, logics, other people and expectations, which Lacan refers to as ‘the Other’. Entry to a socially shared existence comes at a price, and the infant develops from its initial state as “a sort of undifferentiated bundle of sensations, lacking in sensory-motor coordination and all sense of self”, to a “subject split between its symbolic identity and the body that sustains it”.

The subject forever after seeks to mitigate this split through the fantasy of pursuing substitutes, the ‘little other’ in Lacan’s terminology. Money, for example, can be seen as a fantasy object that calls an already wealthy individual to accumulate even more. A foundational logic of the advertising industry is to position products as fantasy objects for its target audience to pursue. The pursuit exerts a powerful emotional grip on the subject which forever affects behaviour at a pre- or unconscious level.

Lacan’s theory of ‘sexuation’ suggests that a masculinity/femininity binary represents two distinct types of responses to this primordial split with which all developing infants, independent of biological sex, engage. As Wright suggests “[a]ll speaking beings insert themselves into this [binary] structure in whatever way they want, in line with their identifications, regardless of their biological sex” [my emphasis]. Their identifications may be conscious or unconscious and are influenced by environment and culture. An individual subject could adopt any combination of this duality.

Masculinity perennially fails to escape the effects of the split through the pursuit of fantasy ‘objects’

Masculinity, as an empirical Lacanian category (not a biological description), is characterised by a total submission to the Symbolic Order while, at the same time, retaining a belief in the existence of a superMan who defies it. (Perhaps this is what helps make the Bruce Willis’ Die Hard or James Bond cinematic tropes so popular). Masculinity perennially fails to escape the effects of the split through the pursuit of fantasy ‘objects’. In a relationship sense, this is often an intimate partner.

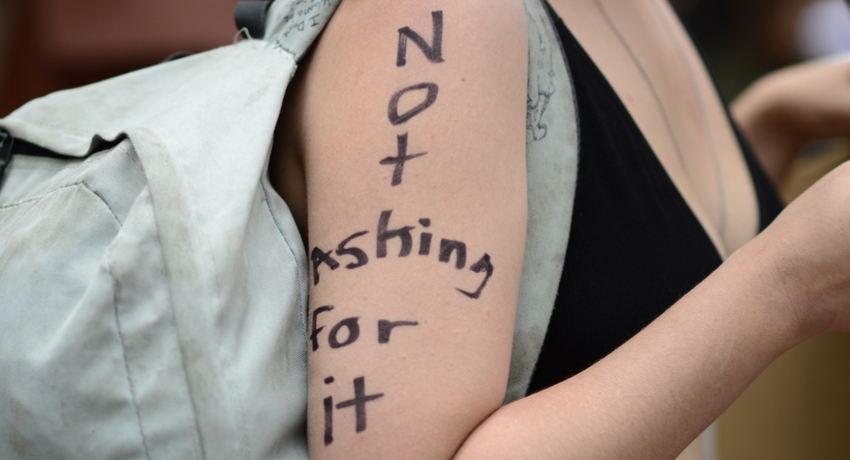

Image: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0

The feminine category, on the other hand, is not totally subsumed by the Symbolic Order. Although always in its presence, femininity has an affinity with something exterior to it, what Lacan refers to (after Heidegger) as an ‘ex-sistence‘.

The suggestion here is that our society pushes biological boys towards Lacanian masculinity, and a Social Order which encompasses ‘the male code‘. This is not to suggest that some biological girls are not similarly driven or that other codes don’t have powerful influence. Lacanians believe that shame is experienced in ‘the gaze’ of the Other, the Symbolic Order. Thus, someone invested in the male code, who does not measure up, experiences shame.

If the fantasy of hunter, protector or warrior, is fractured in the presence of a partner – or worse, because of the partner – the individual feels shame which, as we saw previously, can lead to an existential assault on identity and subsequently to violence.

The obsessive desperation of the sexual predator can clearly be linked to the pursuit of potential sexual partners as fantasy objects

An individual invested in masculinity, who has objectified a ‘loved one’ so that there is no concept of their individual subjectivity, could conceivably become homicidal when faced with an existential crisis grave enough to intimate suicide. Similarly, the obsessive desperation of the sexual predator can clearly be linked to the pursuit of potential sexual partners as fantasy objects.

A Lacanian approach to future prevention of partner and/or sexual violence would require all of us to deal with the social and cultural factors that motivate the unconscious choice of masculinity and femininity in our children’s upbringing. The need for balance, humility and openness, allowing all people to experience a feminine affinity beyond the dictates of a destructive male Social Order is crucial.