The Women’s Economic Security Statement sets out its funding initiatives under three pillars: workforce participation, economic independence and earning potential. While these descriptors accurately describe many of the reforms and new funding streams they are perhaps most interesting for what they leave out.

Pillar one – workforce participation

Initiatives to increase workforce participation include a mix of platforms for cross-sectoral discussion on flexibility, support for employers to attract and retain women, and scholarships for leadership and development. The only reference to the critical issue of gender pay equity under this pillar is in the form of improvements to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s data collection system. Women’s unpaid work, while recognised in the reinstatement of the Australian Bureau of Statistics Time Use survey, is otherwise invisible.

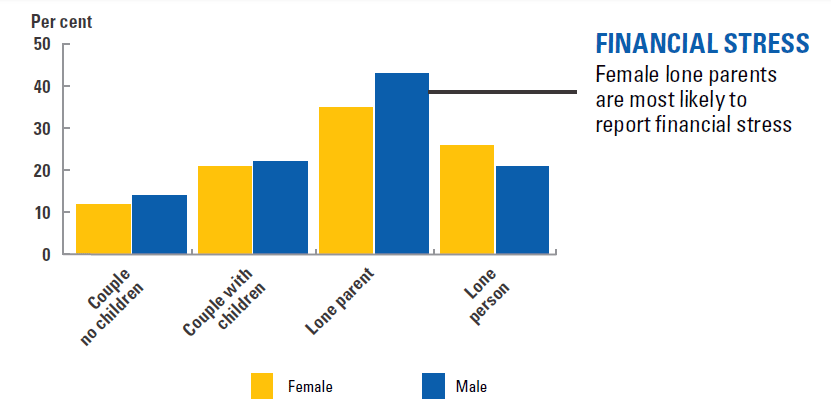

In nowhere is this more apparent than in the restatement of the government’s commitment to jobactive requirements for single parents of children over six and the roll out of ParentsNext to single parents of children as young as six months. As argued elsewhere, these forms of conditional welfare can not only work against financial security and self-sufficiency objectives through excessive compliance requirements, they have very material effects on family wellbeing including food insecurity and poor mental health.

Also missing is a focus on the characteristics of women’s workforce participation

Also missing is a focus on the characteristics of women’s workforce participation. There is no discussion about low wage growth, women’s concentration in low-paying industries and occupations, the increasing casualisation of work, including the proliferation of gig economy, and the poor quality of many part time roles.

Image: Women’s Economic Security Statement

Despite these limitations, there are two standout positive initiatives under this pillar – the changes to parental leave pay and the reinstatement of the ABS Time Use survey.

Parental leave pay

One of the key measures in this package is a change to the government-funded paid parental leave scheme, giving parents more choice in how they use their leave in the first two years of their child’s life. Being able to take the leave in blocks provides more choice and flexibility, including for families who wish to share the care of children in ways that depart from the normative male breadwinner/female homemaker model. Women in non-standard employment and the self-employed stand to benefit from this change.

Having the option to spread the leave over two years will have the added bonus of supporting women in the critical return-to-work period when children start attending child care. As any parent of a young child knows, the first year of child care exposes children to all sorts of viruses (followed by the resulting strengthening of the immune system). For women with little or no access to personal leave to cover children’s sick days, being able to access blocks of leave when sick leave entitlements run out is one small but potentially significant support for women returning to work.

The changes to the work test rules will benefit women who may previously have been excluded from government-funded parental leave pay. This includes women who have irregular work, are on casual contracts or take breaks from employment. This change will benefit women in roles such as relief teachers, or those in hazardous jobs which require an exit in the early stages of pregnancy.

This is another highlight in the statement, demonstrating an understanding that in order to change the trajectory of women’s working lives, we must also change the trajectory of men’s working lives

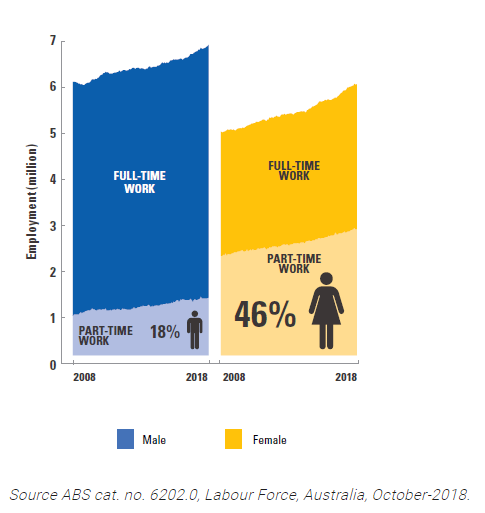

The statement positions the parental leave pay changes and other workforce participation initiatives with reference to the ‘flexibility gap’ in men and women’s use of flexible work arrangements, noting that while 46 per cent of women work part time or in flexible arrangements, only 18 per cent of men do. This is another highlight in the statement, demonstrating an understanding that in order to change the trajectory of women’s working lives, we must also change the trajectory of men’s working lives. ‘Working fathers’ needs to become the new social norm and flexibility policies that entrench women as primary carers over the long term, as opposed to dual carers/earners across the life course, should be discarded.

Image: Women’s Economic Security Statement

Of course many women prefer to be at home with their babies in the early months and years in order to support attachment, establish breastfeeding, recover from childbirth and adjust to the demands of motherhood. There are multiple policy objectives underlying paid parental leave, including supporting infant health, supporting maternal health and maintaining workforce attachment.

Getting a national, government-funded paid parental leave scheme in place was a long and hard haul for advocates, beginning in the 1970s with union women’s demands for 52 weeks of unpaid maternity leave and ending with widespread support across business groups and civil society organisations in the 2000s. Ten years on from the pinnacle of that campaign, now is a good time to reassess the current 18-week scheme with a view to extending the number of weeks to bring us into line with our OECD counterparts, add in a superannuation component, and introduce a ‘use it or lose it’ option for dad and partner pay to increase take-up by men and support the shared care of children in the critical early years.

Time Use Survey

The reinstatement of the ABS Time Use survey is a welcome and overdue initiative. With bipartisan support from the Australian Labour Party (with the ALP committing to two surveys, in 2020 and 2027), there is now a common understanding of the need for this instrument to measure who does what at home and at work.

Only by measuring total work hours (paid and unpaid), including primary and secondary activity, can a full picture of women’s economic status emerge

Only by measuring total work hours (paid and unpaid), including primary and secondary activity, can a full picture of women’s economic status emerge. The data from previous surveys has enabled gendered analysis in relation to a variety of activity including comparisons between coupled and lone parents, time spent in the presence of children, education, personal care, voluntary work and leisure time.

The next step will be to secure a commitment to reinstate the survey over the long term as a core ABS offering. Without this commitment future governments may, as the Australian Labour Party did, cut funding in times of austerity. Six-yearly intervals would enable the meaningful tracking of change over time, including measuring the impact of structural changes in the labour market and the impact of daily care schedules on workforce participation.

Next steps?

While the Coalition’s commitments to improving women’s workforce participation include some welcome announcements, overall it seems to reflect the position expounded by the Federal Social Services Minister Paul Fletcher when he told delegates at the 2018 ACOSS National Conference that “the best form of welfare is a job.”

In essence – the government would like to move more women off of its books and into employment, regardless of the nature of that employment, personal circumstance or costs borne by women and children in various forms. An alternative approach would look more holistically at the structure of the labour market, the barriers to meaningful, secure employment and reality of women’s caring responsibilities across the lifespan.

This article was originally posted on The Power to Persuade blog as part of the Women’s Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens, and has been reproduced here with permission. Follow them on Twitter @PolicyforWomen