Women often have a problematic relationship to the musical world. Female composers in particular have been almost invisible in our standard scholarly body of work. And yet, the problem, as I came to understand first as a student of music and later, as a composer and musicologist, is not that there are no women working in this area. So where exactly are the women? And why don’t we hear more about them?

However, it soon began to dawn on me that women were notably absent from any discussion of the musical canon

I began a music degree in 1990 and I was immediately drawn to both composition and musicology. They always seemed like two sides of a coin, one making sense of the other. However, it soon began to dawn on me that women were notably absent from any discussion of the musical canon.

This struck me as odd and I started to question why. Did it have something to do with education perhaps, and the fact that historically women weren’t given the same opportunities as men, and so wouldn’t have had the education or resources to compose? Or was it perhaps a question about quality? After all, had there been, by some miracle, such a thing as a woman composer then obviously, she would have been in all the standard text books if her work was of sufficient standard. Right?

The reality, as I gradually began to understand, was of course a lot more complex than that. I decided to do some research and get to the bottom of it all. Of course, in those days research was very different to today. The Internet was in its infancy, and research required physically sifting through material in an actual building thumbing through greasy library card catalogues.

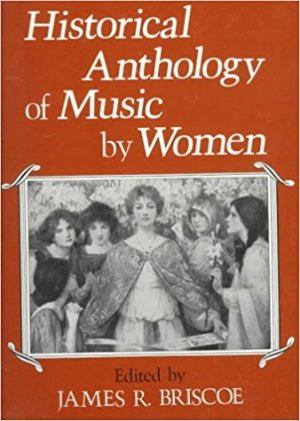

To my surprise, it wasn’t long before I stumbled upon Historical Anthology of Music by Women, edited by James R. Briscoe and published in 1987. It is no exaggeration to say that the moment I picked this book up became a turning point in my life.

To my surprise, it wasn’t long before I stumbled upon Historical Anthology of Music by Women, edited by James R. Briscoe and published in 1987. It is no exaggeration to say that the moment I picked this book up became a turning point in my life.

The music in the book featured no less than 35 female composers giving their biographies as well as a selection of their scores. The historical time period started around 810 AD with a woman only known as Kassia, and finished with Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s (b.1939) first movement of her Symphony No. 1. Best of all, the book came with some recordings of the scores in tape format.

The more I studied the scores and listened to the works from Briscoe’s anthology, the more puzzled and confused I became. Many of the works were very good. They showed a sound sense of craft in terms of musical structure and form, combined with a sure grasp of the lyrical language of music.

One of my favourite discoveries was Hildegard of Bingen, and her fascinating biography. Born in Germany in 1098, she was given to God as a very young girl as a tithe – she was her parents’ tenth child – and sent to grow up in a convent. She was a Christian mystic who wrote poetry, as well as theological, medical, and scientific treatises. She was also a philosopher and botanist, and even invented an alternative to the alphabet. At the age of 43 she began to write down visions that frequently came to her – visions saturated with sensual, vivid, imagery – brilliant and light-filled – often centred around images of the Divine Feminine.

Even though Hildegard had no formal training in music, she composed about 70 musical compositions with original texts and wrote one of the first musical morality plays called, ‘The Order of the Virtues’. Music held a very special place in her life. She believed it was a healing force bringing mind, heart, and body together in a heavenly harmony on earth. Her music was beautiful, but also unusual in its musical contours for the time and genre.

Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard was an avid correspondent – often consulted by leaders of medieval society – popes, kings, bishops, noblemen, priests and nuns. Her opinions and wisdom were highly valued and extant correspondence shows that in her day she was taken seriously as a scholar and valued as a musician.

Which brings us back to my original question: If women were composing, then what exactly was going on?

Which brings us back to my original question: If women were composing – if women’s compositions were good – then what exactly was going on? Why did we never hear any mention of them in standard musical textbooks of the day. Why weren’t any of their works included in the Western art musical canon?

The questions that arose from trying to fathom why women’s music was never heard or performed led me to postgraduate studies, first Honours, and later a PhD. Over the years, I have discovered an incredibly rich and diverse body of music written by women composers that has greatly enhanced my enjoyment of music and made a significant contribution to my own compositional practice.

The answers to my research turned out to be complex, and there are many factors that impact upon women composers’ participation in the musical world. In today’s context, take for example, networking. Networking is essential to success as a composer, but often problematic for women. It requires a good dose of self-confidence, along with ambition and assertiveness, and these characteristics are perceived differently in men and women. Competitions and prizes are another way of gaining a footing in the compositional world, but for many women family considerations often come first. This may mean that their composing career may not begin until later in life – by which time the competitions and prizes are closed due to age limits.

I remember asking one of my classes if they could give me the name of one female composer. Silence. Then a hand went up. “Béla Bartók.” A very fine Hungarian composer, but quite definitely a man.

Works by women can now be found – but finding them still takes dedication and effort on the part of the listener. The practice of exclusion is deeply embedded. There is still a lack of high profile female composer role models for emerging women composers, there are still too few women in academic roles teaching composition and there are still very few women’s works on regular radio play lists. Furthermore, the lack of knowledge about women composers is astounding. I remember asking one of my classes if they could give me the name of one female composer. Silence. Then a hand went up. “Béla Bartók.” A very fine Hungarian composer, but quite definitely a man.

Béla Bartók, Hungarian pianist and composer

We still have some way to go and this requires energy and long-term commitment. We need to keep shining a light on the amazing creative work being undertaken by women across so many artistic fields, otherwise we will be once again notable by our absence.

For those wanting to explore the music of Hildegard of Bingen I highly recommend the album ‘A Feather on the Breath of God’ sung by Emma Kirkby and Gothic Voices.