Australia’s official war art scheme began during the First World war. No women, however, were granted Australian official war artist commissions during this war, although three women artists, Stella Bowen, Sybil Craig and Nora Heysen, were appointed by the Australians during the Second World War. Despite this, a number of women artists did make images of soldiers, battlefields, hospitals, and the home front during the First World War.

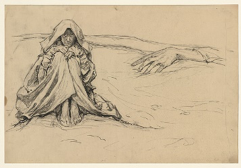

Among those women who painted war subjects are Iso Rae, Dora Meeson, Vida Lahey, Evelyn Chapman and Hilda Rix Nicholas. Printmaker, Jessie Traill, who travelled to London to train as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse and work in a military hospital near Rouen in France, kept illustrated notes from her time as a trainee, in A life at Gifford House 1915 (Manuscript collection, State Library of Victoria).[i]

1.

Other women artists, Daphne Mayo and Dora Ohlfsen, undertook commemorative work following the war. Further women artists, such as Bessie Davidson, were involved in the war effort in Europe and may have painted war works, but all that has come to light by Davidson is a small sketch of a nurse tending a wounded soldier, Hospital Molitor, Paris 1915-16[ii].

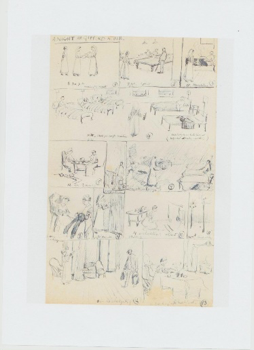

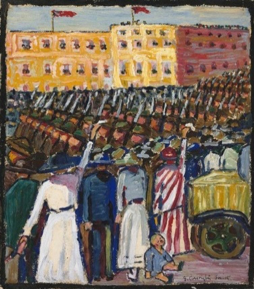

In Australia, Grace Cossington Smith depicted the home front in works such as Reinforcements, troops marching c.1917 and her celebrated The Sock Knitter c.1915, and a good number of drawings of war-related subjects. The Sock knitter is an archetypal image of so many women of this time, enclosed in their rooms, restricted in their occupations, living a somewhat shadowy existence. The painting draws much of its strength from its simplicity of line, as the woman’s lowered eyes lead directly downwards, through the white blouse towards her active hands, the focus of the picture. The eyes, the hands, create a mood of intense concentration on the task at hand.

It is, a wartime theme, a scene of a woman working for the good of the nation, contributing to the survival of the soldiers in the trenches by knitting socks to send to them, to keep their feet protected from frostbite.

In Britain, Margaret Preston and Gladys Reynell worked at a canteen for soldiers and sailors as part of the war effort, and then towards the end of the war, from August 1918, taught shell-shocked soldiers ceramics, basketmaking and weaving at the Seale Hayne Neurological Hospital in Devon. The task required some ingenuity as traditional materials were unavailable.

The Australians failure to appoint women as official war artists during the First World War was due to a number of factors. Many Australian women were keen to become involved in ‘war work’, but they were not welcomed into the workforce in Australia in the same way as they were in Britain and Europe. Indeed, women were basically excluded from participating in this war in any capacity other than as nurses and related activities, or on the home front. In Australia, their service was almost wholly restricted to the domestic sphere – to providing comforts by knitting socks or visiting the families of servicemen, to raising funds and organising patriotic entertainments.

Nonetheless, more than 3,000 Australian civilian nurses volunteered for active service during the First World War. The Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) had been formed in July 1903 as part of the Australian Army Medical Corps and during the war more than 2,000 of its members served overseas alongside Australian nurses working with other organisations such as the Red Cross. Many of those women who served overseas paid their own fare and joined the British forces or trained as VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurses.[iii]

Those male artists who received official appointments during the First World War were either expatriate artists of some standing (and age) who resided in London, or artists who had joined the forces and who were later selected to receive camouflage training and undertake pictorial records. No artists were appointed from Australia. So, if women artists were to have been appointed by the Australians, they would have needed to be already living in Europe. But there were a number of women artists, such as Iso Rae, Dora Meeson, Vida Lahey and Hilda Rix Nicholas, who had travelled abroad before or during the war, and despite the lack of official appointments, managed to produce war art worthy of consideration.

Iso Rae had been living in Étaples on the coast of northern France for around twenty years before the war broke out. She had been trained in Melbourne, and she travelled to Europe in 1887 to further her art studies. Étaples was an ancient fishing port which during the war housed a large number of British supply and reinforcement camps, as well as many hospitals. In 1915 a camp for wounded German prisoners was also established in Étaples. In addition, the town was a training and staging post for soldiers moving to and from the front.

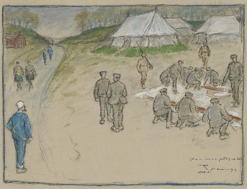

4.

German prisoners was also established in Étaples. In addition, the town was a training and staging post for soldiers moving to and from the front.

As a member of the Voluntary Aid Detachment Rae worked at the Étaples Army Base Camp throughout the war. There, she made a valuable contribution to the war effort as well as finding time to produce a large number of pastel drawings portraying aspects of military life in Étaples and nearby areas. These include scenes of the troops marching into camp and returning from the training ground, as well as ones showing men eating in the canteen, queuing for the cinema and playing football. Inevitably, some depict nurses caring for the wounded in hospital. Some portray German prisoners.

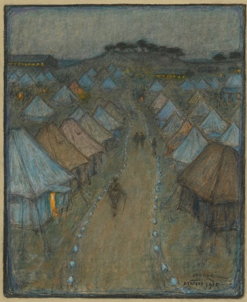

5.  Working in pastel, and emphasising the forms in heavy black outlines, Rae focused on the poetic and decorative aspects of the scene and made use of the rhythmical patterns of the bell-shaped tents and the rows of hospital huts, as well as the repetitive movement of the marching troops. She explored atmospheric night scenes: a light radiating from a tent opening, glimmering from hut windows, or a searchlight roaming the sky.

Working in pastel, and emphasising the forms in heavy black outlines, Rae focused on the poetic and decorative aspects of the scene and made use of the rhythmical patterns of the bell-shaped tents and the rows of hospital huts, as well as the repetitive movement of the marching troops. She explored atmospheric night scenes: a light radiating from a tent opening, glimmering from hut windows, or a searchlight roaming the sky.

She was a vital eye-witness who captured unique images not portrayed by any other artist. She did not reveal the slaughter at the front or the suffering of soldiers in hospital and mostly portrayed the scenes from afar, using a panoramic viewpoint and with a high elevation. However, some of her images of German prisoners – outsiders, like herself – show these men from a closer, more direct perspective.

6.

She observed the men’s active, public world, a universe she was not part of, but viewed from the side. In this, her images sum up the experiences of most women in this war, who saw events from a different perspective from the men.[iv]

Dora Meeson, who had studied at the Melbourne National Gallery School, and later at the Slade School in London and in Paris under Benjamin Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens worked as a policewoman on night-duty in an ammunition factory during the war. She painted a number of war-related subjects. She was the artist wife of the artist George Coates, who served as an orderly at the 3rd London General Hospital at Wandsworth during the war. Living in London, she was all too aware of the bombing. In her biography, George Coates, his art and life, she vividly describes several occasions when she needed to hide in the coal cupboard shivering while the German bombers flew overhead. [v] She would also have been all too aware of the many departures of soldiers for the front. In Leaving for the front 1916, she made a poignant image of life on the home front in Britain, depicting a soldier on the point of departure, saying farewell to his wife and family.

7.

Conscious of the importance of medical activities she depicted one of medical ships leaving Britain in Departure of the last Australian hospital ships from Southampton 1919 (Australian War Memorial). This ship, probably the Karoola, which transported sick and wounded between England and Australia, making a total of 13 voyages.

8.

She was also able to observe the peace celebrations in London in 1919, with the Indian Troops marching in the Victory Parade on 19 July, and civilians flocking to take part in the festivities.

Another former Melbourne National Gallery School student, and a Brisbane art teacher, Vida Lahey went to London in 1916 to provide a base for her soldier brothers, Jack, Noel and Romero who had enlisted in the AIF. En route, she painted a watercolour of Australian troops at Aden. Then, in London she became involved in providing a variety of assistance as part of the war effort: she worked for the ANZAC buffet, undertook hospital visiting and assisting with the organisation and supervision of weekly outings for groups of convalescent soldiers, and otherwise helped with Red Cross Society activities.[vi] Lahey had her own sadness. Her brother, Noel, was injured at Messines and died shortly afterwards, and Jack was wounded twice, and invalided to Australia. She would have been relieved when the armistice was announced, and grateful that at least two of her brothers had survived the war. In Rejoicing and remembrance she recorded her mixed emotions. It is a strong example of her work, expressing the response of Londoners to the end of the war.

9.

She commented that this painting ‘shows the portico of St. Martins-in-the-Fields, with the shouting and dancing outside, but I have aimed more at truth to the feeling of the scene than strictly literal truth’.[vii] The joyous swirling figures of the rejoicers entering the image from the right are contrasted with the solemn stooped shapes of those remembering the dead, who are portrayed departing on the left. Flags fly high through the columns of the portico which tower over the crowd, giving a sense of pomp and grandeur to the scene. Here, Lahey revealed her talent to portray a poignant moment in history.

A series of views of the area around Villers-Bretonneux were painted by Evelyn Chapman, while accompanying her father, Francis Chapman on a tour of the battlefields following the war.

10.

He was a member of the New Zealand War Graves Commission, and visited France with a view to reclaiming and re-burying the bodies of New Zealand soldiers who had died. She had gone to Europe in 1911 with her parents where she had furthered her art studies in Paris at the Academie Julian. Her paintings of post-war France are of scenes of devastation and include depictions of church ruins, a street in a bombed village and a landscape with defoliated trees beneath a dark stormy sky.

She was one of many artists who depicted battlefield devastation during the First World War.

11.

The damage was shocking, and artists portrayed it to convey their dismay. Chapman particularly observed the rubble and hollow remains of ruined churches; she showed these spiritual monuments as having been ravished, left empty and abandoned. Her images are painted in a bright, vibrant palette, and with simplified forms and flattened picture space. She used the sharp, jagged shapes of the ruined buildings to express the discord of war, a durable account of the casualties of war.[viii]

12.  When compared with the works of similar subjects by the official war artist Arthur Streeton, Chapman’s images can be seen to lack the power of Streeton’s. Perhaps this was because her exposure the scene was after the war and not through any deep personal experience. However, as a woman civilian Chapman was fortunate in having the opportunity to visit the battlefields and to view as much as she did so soon after the war, and left a valuable record of what she saw there.

When compared with the works of similar subjects by the official war artist Arthur Streeton, Chapman’s images can be seen to lack the power of Streeton’s. Perhaps this was because her exposure the scene was after the war and not through any deep personal experience. However, as a woman civilian Chapman was fortunate in having the opportunity to visit the battlefields and to view as much as she did so soon after the war, and left a valuable record of what she saw there.

Hilda Rix Nicholas’ studies of soldiers stand up well beside those of the official war artists. She had gone to Europe with her family in 1907, where she continued her studies in art and travelled widely, settling for a time in Étaples. The First World War was a time of tragedy and loss for her. Encouraged to leave France and move to England at the beginning of the war, her mother and sister contracted enteric fever during their evacuation. Her sister Elsie died in September 1914, and her mother in early 1916, and Hilda found herself alone.

By October 1916, she had met, and married, George Matson Nicholas DSO. They enjoyed a brief honeymoon before he returned to France and but he was killed in action five weeks after their wedding; hit by a stray shell, like so many others.

13.

She despaired, writing: ‘I would have died, had I been allowed – I was so near. I wanted to go. But my friends again patched me up’[ix]. Her four younger brothers who had enlisted in the AIF occasionally visited London on leave and gave her all the support they could. However, two of her brothers were later killed in action, and another suffered from shell-shock. Painting helped her come to terms with her grief. However, bad luck dogged her and some of the powerful works Nicholas produced while living in London as a result of her sorrow, such as Desolation 1917 and Pro Humanitate 1917, were destroyed in a house fire in 1930.

Following her return to Australia in 1918, Nicholas continued to paint war-related works like A man, which commemorates the heroism of the Australian soldier.

15.

Using a returned serviceman as a model, Nicholas portrayed him wearing full dress uniform, and holding a gun barrel firmly in his hand. Behind him, the stormy sky suggests that his life may be limited. Nonetheless, depicted in profile with a determined gaze, this soldier exudes a sense of physicality. He is the epitome of the rugged Australian hero, an idealised, strong, masculine figure Such images prefigure those of Ivor Hele in the second world war in their depictions of the archetypal Australian soldier.

Powerful, in a different way, is Hilda Rix Nicholas’ representation of A mother of France. This painting conveys with simplicity and understatement, the sorrow brought about by war and the wisdom that comes with endurance. The subject is her neighbour at Étaples, who had lost her husband in the Franco-Prussian war, and then her sons in the First World War.

16.

Nicholas started it in France and completed it in England, after she had become a widow herself. Through the questioning gaze and the tension of the hands, a character is created and a story told.

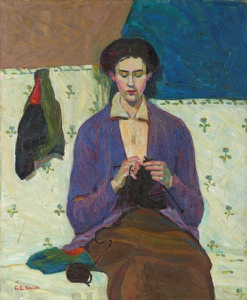

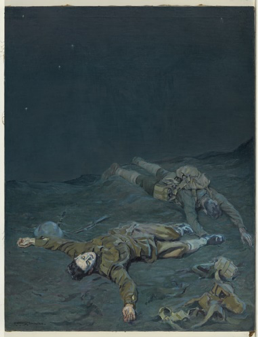

One of the works that Nicholas painted in London, These laid the world away 1917 is a highly personal painting.

17.

Traumatised, after her husband had been killed in action, Nicholas could easily imagine the horrors experienced by those at the front, and the suffering of their loved ones. This work, showing two dead soldiers (one, her husband) lying on the rough ground of a battlefield, is a vivid expression of this personal experience. The cold, steely grey sky and ground, add to the sombre tone of the painting. The title may well refer to Rupert Brook’s powerful poem, The dead, first published in April 1915, with the lines ‘These laid the world away; poured out the red/ Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be/ Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene, / That men call age; and those who would have been’.

18.  When Grace Cossington Smith saw Nicholas’ war paintings exhibited in Sydney in 1919, she wrote to her friend Mary Cunningham:

When Grace Cossington Smith saw Nicholas’ war paintings exhibited in Sydney in 1919, she wrote to her friend Mary Cunningham:

The one who painted all this had to paint just as the feeling was – I suppose it could be called emotional painting – the painter was not left untouched by the war … the tragedy of the war … The strange part is all this was painted by “only a woman” … Of course, really, only a woman could paint like that …[x]

Dr Anne Gray

First published in Julia Church and Alison Alder, True bird grit: a book about Canberra women in the arts 1982-83, Acme Ink, Canberra, 1982.

Expanded February 2018.

Images…

1. Jessie Traill

A night at Gifford house 1915

Pen and ink on paper

Manuscripts collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne

2. Grace Cossington Smith

Reinforcements, troops marching c..1917

oil on paper on hardboard 23.7 x 21.5 cm;

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

3. Grace Cossington Smith

The sock knitter c.1915

oil on canvas 61.8 x 51.2 cm;

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

4. Iso Rae

German prisoners putting up tents 1917

pastel with touches of gouache on light grey-fawn paper 39.4 × 52.7 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

5. Iso Rae

Etaples 1915

colour chalks and charcoal on paper 55.2 x 46.1 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

6. Iso Rae

Etaples: German prisoners working on a railway April 1917

colour chalks and charcoal on paper 26.8 x 41.6 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

7. Dora Meeson

Leaving for the front c.1916

oil on canvas 152 x 122.c cm

Ballarat Art Gallery

8. Dora Meeson

Peace Celebrations, Indian Troops Marching 1910

oil on canvas 61 x 50.8 cm

National Army Museum, London, gift of the artist

9. Vida Lahey

Rejoicing and Remembrance — Armistice Day, London 1918

charcoal and watercolour 74.5 x 56 cm

Australian War Memorial, Canberra

10.Evelyn Chapman, on the battlefields July 1919

11. Evelyn Chapman,

Old trench, French battlefield 1919

tempera on textured grey paper on cardboard 54.0 x 73.3 cm

Art Gallery of new South Wales, Gift of the artist’s daughter Pamela Thalben-Ball

12. Evelyn Chapman,

Ruined church, Villers Brettoneux 1919

oil? on thick grey card 41.3 x 56.3 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Bequest of Pamela Thorban-Ball

13. Hilda Rix Nicholas

Major George Matson Nicholas c.1916

charcoal and pastel over pencil on paper 56 x 38 cm;

Australian War Memorial, Canberra

14. Hilda Rix Nicholas

Sutdy for the painting ‘Desolation’ c.1917

charcoal on paper 38.2 x 56.0 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

15. Hilda Rix Nicholas

A man c.1916

oil on canvas 92 x 75 cm

Australian War Memorial, Canberra

16. Hilda Rix Nicholas

A Mother of France c.1916

oil on canvas 73 x 60.5 cm;

Australian War Memorial, Canberra

17. Hilda Rix Nicholas

Study for ‘These laid the world away’ 1917

charcoal on paper 33.8 x 55.8 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

18. Hilda Rix Nicholas

These laid the world away 1917

oil on canvas 127 x 97 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Footnotes

[1] Jessie Traill, ‘A Night at Gifford House’, London, 1915, ink on paper. ‘Gifford House’,

Jessie Traill Papers, Australian Manuscripts Collection MS 7975, Box 796/1(a); Jo Oliver, ‘From Harkaway to Amiens: Jessie Traill’s war’, Latrobe Library Journal, no 93, September 2016, pp.108=123.

[1] Penelope Little, A studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson, an Australian artist in Paris, Craftsman House, 2003, p.71.

[1] See Michael McKernan, The Australian people and the Great War, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980; and Jan Bassett, ‘Australian women and the Great War’, Australian Military History Conference, 1982.

[1] See Anne Gray, ‘Isobel Rae’, inJoan Kerr and Anita Callaway. Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Craftsman House, Roseville East,.1995, p. 434

[1] Dora Meeson Coates, George Coates: his art and life, J.M. Dent, London, 1937,

[1] Vida Lahey, autobiographical notes, 1956, in Vida Lahey Scrap Book, John Oxley Memorial Library, Brisbane, OM67-30.

[1] Vida Lahey to the Director, Australia War Memorial, 31 October 1924.

[1] See Anne Gray, ‘Evelyn Chapman’, inJoan Kerr and Anita Callaway. Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book, Craftsman House, Roseville East,.1995, p. 327.

[1] Hilda Rix Nicholas, quoted in Karen Johnson, In search of beauty: Hilda Rix Nicholas’ sketchbook art, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2012, p,23.

[1] Perseus (Grace Cossington Smith) to Madame Medusa (Mary Cunningham), 10 August 1919, Cunningham Family Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 6749, quoted in Catherine Speck, ‘Meditations on loss: Hilda Rix Nicholas’ War’, Artlink, March 2015.