The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Gender Initiative aims to enhance gender equality in education, employment, entrepreneurship and public life through legislation, policies, monitoring and campaigns. The organisation’s recently released Report on the implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations calls on member countries, and non-members who adhered to the recommendations, to enhance gender equality across various sectors.

It indicates that while many countries have taken steps to prioritise gender equality in policy and practise, gender gaps in key areas have proven to be persistent.

The recommendations are premised on the acknowledgement that despite existing policies:

“significant gender disparities and biases nevertheless remain in educational and occupational choices; earning levels and working conditions; career progression; representation in decision-making positions; in public life; in the uptake of paid and unpaid work; in entrepreneurial activities; in access to finance for entrepreneurs; and in financial literacy and financial empowerment.”

So, where exactly are we at?

Education

Education yields mixed results for men and women. In OECD countries, girls and young women often outperform boys and young men in educational attainment and proficiencies. Girls tend to do better in reading, and boys in mathematics, but in most OECD countries the gender gaps have started to narrow. Across the OECD, more women than men obtained tertiary qualifications in 2014.

Despite outperforming boys at school, girls remain under-represented in STEM fields, with little change since the adoption of the OECD Gender Recommendations. Women account for less than 20% of computing and engineering graduates, which likely reflects gender differences in career expectations and persistent stereotypes regarding the suitability of the career choices for boys and girls.

Despite outperforming boys at school, girls remain under-represented in STEM fields, with little change since the adoption of the OECD Gender Recommendations.

Tertiary-educated women are now also more likely to emigrate to OECD countries than their male counterparts. This female ‘brain-drain’ presents challenges for countries of origin as women’s education is an important determinant of growth. Flexible policy responses are required in order to tackle the specific needs of migrant women, but few countries have developed systematic policies.

Employment

Gender gaps in education feed into gender gaps in employment. While the gap has been narrowing, women are still less likely to be in the workforce across the OECD, and more likely to work part-time or in lower paying jobs.

While the gap has been narrowing, women are still less likely to be in the workforce across the OECD.

Factors contributing to the employment gap include lower labour participation, higher probability of careers being interrupted by caring duties, and higher likelihoods of working part time. Less tangible factors such as discrimination also lead to attrition in the number of women who advance to upper management, contributing to what the OECD terms ‘the leaky pipeline’.

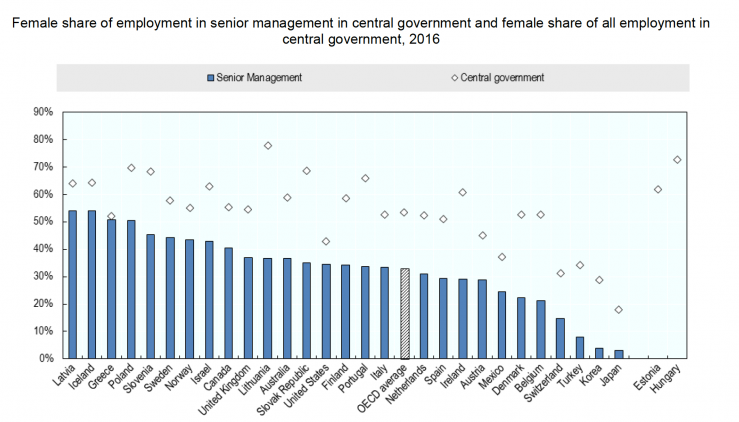

While member countries have experienced modest progress, women make up less than one-third of managers in the OECD on average, though there is considerable variation across countries. Gender balance at the top of listed companies is also a distant goal, with women occupying 20% of board seats of publicly listed companies; on average, 4.8% of CEOs were women in 2016.

Countries that have adopted quotas to promote gender balance on boards and in senior management have seen more immediate increases in the number of women on boards, while those that have taken a softer approach using disclosure or targets have seen a more gradual increase over time.

Countries that have adopted quotas to promote gender balance on boards and in senior management have seen more immediate increases in the number of women on boards, while those that have taken a softer approach using disclosure or targets have seen a more gradual increase over time.

Countries that have adopted quotas to promote gender balance on boards and in senior management have seen more immediate increases in the number of women on boards.

Migrant status continues to be a barrier to employment in OECD countries, especially for women who are ‘double disadvantaged’ in the labour market when compared with native-born women, and migrant men. In traditional settlement countries like New Zealand, Canada, Australia and the United States, employment rates for migrant women are all higher than the OECD average.

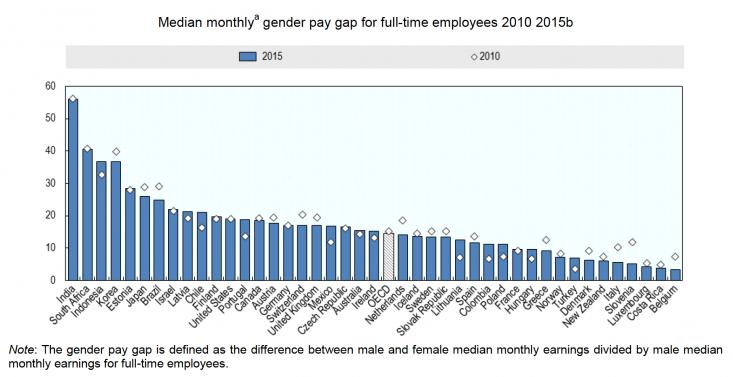

Considering women’s high educational attainment, in theory women should earn more than men. However, gender pay gaps have changed little across the OECD and G20 countries, remaining at a median of 15% across the OECD on average.

However, disentangling the effects of observable and non-observable characteristics such as discrimination in hiring, career progression and pay is not easy. While age, education, occupation and industry are becoming less important in explaining the gap, the under-representation of women in the top income group remain overwhelming.

However, disentangling the effects of observable and non-observable characteristics such as discrimination in hiring, career progression and pay is not easy. While age, education, occupation and industry are becoming less important in explaining the gap, the under-representation of women in the top income group remain overwhelming.

One promising policy measure involves pay transparency, with many countries either proposing or introducing measures to share information with employees, government auditors and the public.

One promising policy measure involves pay transparency, with many countries either proposing or introducing measures to share information.

Other positive measures include pay gap calculators that help employees better understand what salary they should receive for a given job, and certifications for award for companies showing a commitment to reducing the gender pay gap.

Entrepreneurship and public life

The introduction of political affirmative action in electoral legislation, or in some cases, in constitutions has contributed to an increase in the share of elected women in emerging economies, but in many cases thick glass ceilings still exist. However across the OECD, women hold only 28.7% of seats in lower houses of Parliament.

Across the OECD, women hold only 28.7% of seats in lower houses of Parliament.

While women make up 55% of all judges (according to available national data), their presence decreases when moving up the judicial hierarchy. In the private sector in 2016, women occupied 20% of board seats of publicly listed companies and only 4.8% of chief executive officer positions.

On the other hand, women have more than doubled their representation in lower or single houses of Parliament across the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region, with Algeria and Tunisia having crossed the 30% threshold deemed by the United Nations to be the tipping point for women to truly influence policy.

Where to from here?

Unsurprisingly, motherhood – much more than fatherhood – still presents one of the biggest barriers for women’s equal representation. Consequently, increasing fathers’ participation in unpaid care and housework is a key tool for achieving gender equality.

Most countries noted that making child care more accessible would be the most effective method for removing barriers to women’s employment, along with equal pay, flexible work arrangements, and increasing women’s access to better quality jobs.

It’s not all negative, however. The narrowing gender gaps in education, as well as the labour market behaviour of young women and men give us some cause for optimism.

Narrowing gender gaps in education, as well as the labour market behaviour of young women and men give us some cause for optimism.

To ensure further progress, the report urges countries to “step up their efforts to ensure that public policy truly reflects – and results in – more inclusive societies, in which boys, girls, men and women can all reach their true potential”.