The OECD’s latest report, which follows the 2013 OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship and the 2015 OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life, identifies important gender gaps and offers policy recommendations on how to resolve them.

While policies are changing for the better, much more improvement is needed. Gender gaps still exist in all areas of social and economic life and in all OECD countries and key emerging economies. True, young women in OECD countries now frequently obtain more years of schooling than young men, but girls continue to under-perform and are less likely to study in more lucrative science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

While policies are changing for the better, much more improvement is needed.

Women’s labour force participation rates have moved closer to men’s over the past few decades, but women are still less likely than men to take up paid work in every OECD country. When women do work, they are more likely to work part-time, are less likely to be in management, and will likely earn less than men.

The median female worker earns almost 15% less than her male counterpart, on average, in the OECD area. Women are also underrepresented in political office, holding, on average, fewer than a third of seats in lower houses of national legislatures in OECD countries.

But there is some cause for optimism. In fact, many countries are starting to make the grade in three policy areas: promoting fathers’ leave-taking, targeting the gender wage gap, and combating violence against women.

The median female worker earns almost 15% less than her male counterpart, on average, in the OECD area.

Take paternity leave and fathers’ parental leave first. Fathers’ unpaid care-giving is crucial for establishing an equal division of unpaid work at home and for enabling mothers to enter and advance in the labour force. Many countries understand this, and now offer paid paternity leave for the time around childbirth.

Since 2013, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Italy, and Turkey have introduced statutory paid paternity leave. Other countries, including Japan, Korea, Norway, Sweden, and Germany, are reserving a leave period that only fathers can use.

Fathers’ unpaid care-giving is crucial for establishing an equal division of unpaid work at home.

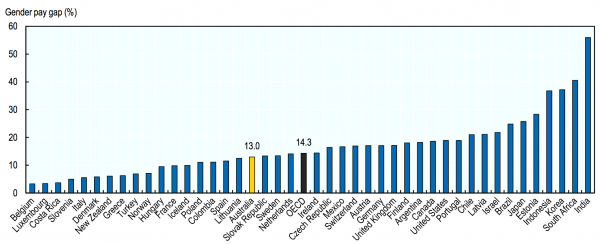

What about the pay gap? Women in the labour force still earn less than their male counterparts in every OECD country (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Gender pay gap (2015 or latest available year).

Figure 1: Gender pay gap (2015 or latest available year).

Since 2013, about two-thirds of OECD countries have introduced new pay equity policies. These include pay transparency and the requirement that companies not only carry out analyses of gender wage gaps but also share that information with employees, auditors, or the public.

Since 2013, about two-thirds of OECD countries have introduced new pay equity policies.

Since 2013, pay transparency tools have been implemented or proposed in Australia, Germany, Japan, Lithuania, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK. Other countries are trying new strategies, like online pay gap calculators and certifications for companies showing good practice. The recent creation of the Equal Pay International Coalition (EPIC), convened by the ILO, OECD, and UN Women, should also help nudge countries forward on pay equality.

Beyond these important pay and care issues, preventing and ending violence against women is widely reported by governments as the most urgent gender equality issue among OECD countries and adherents to the OECD Gender Recommendations (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Priority issues in gender equality across 35 OECD countries.

Figure 2: Priority issues in gender equality across 35 OECD countries.

Austria, Costa Rica, France, Iceland, Israel, Korea, Mexico, Portugal and Slovenia have introduced or reinforced anti-harassment laws.

Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Israel, Korea, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Portugal have initiated awareness-raising campaigns about sexual harassment and its different manifestations. And Australia, Mexico, and Sweden have gone further in taking national, whole-of-government approaches to sanctioning and preventing violence against women.

Gender equality remains a distant goal. Clearly, governments must act more urgently in reforming and strengthening their gender equality policies. Without a renewed commitment, as our report details, the struggle for gender equality will remain an uphill battle indeed.