Imagine being a woman in a country where single women are refused mortgages; without a husband, women are not eligible for loans or the new homeowner grants; married women temporarily out of work are not eligible for unemployment benefits; working women who pay the same amount of tax as men are not eligible for the same social services; widows only receive 5/8th of the pension if her husband dies; applications for scholarships require the signature of a father; and women can not fill in their own customs declarations.

This may sound like a dystopia, but in fact, these were the realities facing women in Australia as recently as 1971. With women’s rights increasingly under the threat of being wound back all over the world, we need to remind ourselves of the fraught nature of the social structures we often take for granted.

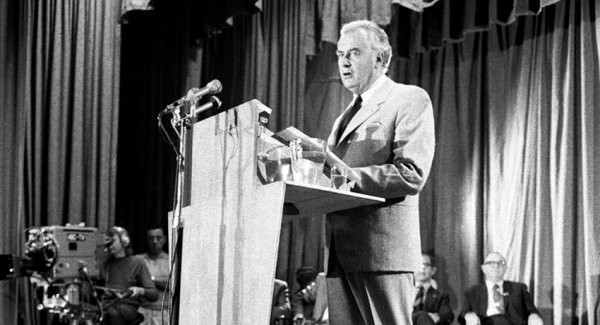

If there was ever a divisive figure in Australian politics, it was Gough Whitlam

If there was ever a divisive figure in Australian politics, it was Gough Whitlam. In government 1972 – 1975, he is widely remembered for his untimely exit from politics in 1975, when the Governor General Sir John Kerr used his reserve powers to dismiss the Prime Minister after the Senate refused to pass supply. But regardless of where one sits on the political spectrum, his government’s significant achievements to progress gender equality in Australia show how much can change in a short period of time when there’s a concerted push to reform society.

During his 1972 campaign, Gough Whitlam included three reforms specifically targeting women. He promised equal pay for work of equal value; the removal of the sales tax on contraceptives; and access to preschool education for all Australian children under the age of five.

Gough Whitlam delivering the Australian Labor Party’s 1972 election policy speech at the Blacktown Civic Centre in Sydney. Image: National Archives of Australia

Remarkably, once elected, he also acted upon these promises. In the first week of the government, Whitlam removed sales tax from the contraceptive pill and made oral contraceptives available via the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. His government provided funding for women’s organisations, newly established women’s health centres and the first ever women’s refuges. In addition, family planning services were funded so women had better control over their fertility.

Among his first acts in Government was reopening the National Wage and Equal Pay cases at the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. Whitlam appointed Elizabeth Evatt as commissioner, who later went on to chair the Royal Commission on Human Relationships, and sit as the inaugural Chief Justice of the Family Court. The 1972 Equal Pay case meant that women in Australia should be paid an equal wage to men in Australia for doing similar work. Half a million female workers became eligible for full pay, and an overall rise in women’s wages of around 30% resulted from this case. Two years later, the commission extended the adult minimum wage to include women for the first time ever.

Women working in the public service, which at the time employed upwards of 64,000 women, also saw their conditions improve with the passing of the Maternity Leave Act, which offered 12 days of full pay, and 12 months of unpaid leave for new mothers employed by the Commonwealth and outlawed pregnancy related discrimination. Partners in same sex relationships received the same benefits as spouses for diplomatic postings.

Whitlam helped to make the personal political by creating the Royal Commission on Human Relationships, one of the most ambitious social inquiries in Australian history. The commission emerged after a failed attempt to reform abortion law in the ACT in 1973 and it was tasked with investigating the ‘family, social, educational, legal and sexual aspects of male and female relationships’. Private problems like domestic violence, sexual assault, abortion, child abuse, and experiences of parenthood were put on the political agenda. The Commission’s extensive recommendations articulated and anticipated a feminist reform agenda that would roll out across the following decade.

In 1973, the Whitlam Government appointed Elizabeth Reid as the first Adviser on Women’s Affairs.

Key to the establishment of this Commission was Elizabeth Reid, the world’s first adviser on women’s affairs to a national leader. She worked inside the Prime Ministers office, and advocated for all submissions to cabinet to include an assessment on their impact on women. According to political scientist Marian Sawer, she achieved an almost ‘quasi-ministerial status’. Beside the Prime Minister himself, Ms Reid received the most letters of anyone in cabinet. A valued member of the women’s movement, this signaled a commitment to listening to women’s advocates and working with them, rather than against them.

Whitlam was resolute in his belief that matters of the home were political. He passed the Family Law Act 1975, which paved the way for a national Family Court. Furthermore, no fault divorce was introduced, meaning that a marriage could be ended due to the irretrievable breakdown to be established by a 12-month separation, rather than evidence of infidelity.

In 1974, single mothers were granted access to financial assistance, and a pension was introduced for low income sole parents (now called the Parenting Payment Single) . Previously, such supports had only existed for widows and deserted wives. This meant that mothers were able to choose to keep their children rather than given them up for adoption. Whitlam referred to this reform as “the most significant single innovation in social security for a generation”.

Whitlam also understood that for women to participate fully in the workforce, more diversified and integrated child care services were needed

He also understood that for women to participate fully in the workforce, more diversified and integrated child care services were needed. In 1972 the Child Care Act was passed providing for grants to non-profit agencies to provide child care facilities. This was the first time a Commonwealth Government became financially involved with childcare.

The Women and Politics Conference (held in 1975, International Women’s Year) was funded by Whitlam and spearheaded by Reid, bringing over 700 women together from all over Australia to discuss the political role of women. It aimed to increase the “understanding of the prejudices and beliefs which generally exclude women from political life, and of the changes necessary to enable them, and all women, to freely participate in the decision-making that affected their lives”.

Australian delegate Elizabeth Reid addresses the World Conference of the International Women’s Year, at Mexico City in 1975.

All of these reforms faced strong opposition at the time. Even nominal gestures such as the introduction of the term “Ms,” caused an outcry.

So where does this leave us now?

Just as equality is not an accident, progress is not inevitable

Just as equality is not an accident, progress is not inevitable. Research has shown that many believe gender equality has been achieved, or that it is not a burning issue.

Currently, research suggests that women will not achieve economic parity with men for 215 years, CEO parity will not be achieved for 80 years, and women are still victims to epidemic levels of violence, with on average one woman losing her life every week. Most people hold the assumption that we will naturally progress, although given that we have slipped 24 places in the Global Gender Equity rankings since 2006, momentum is not something that can or should be ever taken for granted.

What we need now is the courage to prioritise women’s issues to ensure that the hard-won gains are not lost. The question that remains – is the next government up to the task?