Fellow journalists; ladies and gentlemen

When I joined the Canberra Press Gallery as political correspondent for the Australian Financial Review in 1979 there were no women members of the House of Representatives. Not one.

There had been women members in the past – although not many – in fact, just four.

In the seventy-three years between the first federal election in 1901 and 1974 when Joan Child won the Victorian seat of Henty, only four women were elected to the lower house of our federal parliament.

Child lost her seat in the 1975 anti-Whitlam landslide which is how there came to be no women in the Reps when I arrived in Canberra in 1979.

I am glad to say the pace picked up a bit with the 1980 federal election.

Three women won seats in the Reps that year, including Joan Child who was returned in her old seat of Henty. In 1986 Child became the first woman Speaker of the House of Representatives.

And of course, the pace has accelerated mightily since then with a total of 215 women now having been elected to serve in our federal parliament.[i]

But for most of my first two years working in Canberra there were more women bureau chiefs in the Press Gallery than there were female members of the House of Representatives.

Fast forward forty years to 2019 and what has happened?

Short answer: a lot. Two hundred and fifteen federal women MPs is no small thing. Even if it is over 118 years.

But the longer answer has to be: not nearly enough.

If I can summarise where we are today, there are 75 women in the current parliament: 30 Senators and 45 members of the House of Representatives.[ii] What is especially interesting is that although women are a higher percentage of the Senate – they make up 39 per cent of Senators, compared with only 30 per cent of members of the House of Reps — their absolute numbers are now higher in the Reps. This is a significant change because of course a Prime Minister is drawn from the Reps and with more women in that Chamber the chances are higher – in theory at least – of a woman once again getting the top job.

Many milestones have been reached and barriers broken in the past forty years

Many milestones have been reached and barriers broken in the past forty years.

Two women, Joan Child and Anna Burke, have been Speakers of the House of Representatives and Senator Margaret Reid has been President of the Senate. Janine Haines became the first woman to lead a political party in 1986, women have been deputy leaders and of course in 2010 Julia Gillard because the first Australian woman to be Prime Minister.

Quentin Bryce swearing in Julia Gillard as Prime Minister

Women are now routinely members of Cabinet, even if not always in sufficiently high numbers. Women have held economic portfolios such as Finance and Assistant Treasurer and have held the high-status and nationally significant portfolios of Defence and Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Women now enter parliament at a far younger age than was usual in the 1970s, often still of child-bearing age and this has led to other barriers being broken: Ros Kelly becoming the first woman MP to give birth in 1983, and in 2017 Kelly O’Dwyer the first Cabinet member to have a baby.

I should say, the first female one. It has become commonplace for women ministers to have young children, to breastfeed at work and to need to juggle child-care along with running their portfolios. But it has not yet become commonplace for male ministers to bring their kids to work and to have to worry about juggling.

It has become commonplace for women ministers to have young children and to breastfeed at work

It has become commonplace for women ministers to have young children and to breastfeed at work

When she was Attorney-General in the Gillard government (and, incidentally, the first woman to occupy this position) Nicola Roxon used to make the point that while she was constantly asked how she managed such a big job when she had a toddler, none of her male Cabinet colleagues with similarly young children were ever asked this question.

At the same time as women were making their mark in the federal Parliament, elsewhere in government women were occupying new and ground-breaking positions. Quentin Bryce became the first woman Governor-General, women went to the High Court (with Susan Kiefel becoming the first woman chief justice in 2017), women become ambassadors, including to China, were appointed to run government departments and and began occupying a wide range of positions that could scarcely have been imagined in 1979.

This is not to say that full equality has been achieved, let alone nirvana

This is not to say that full equality has been achieved, let alone nirvana.

There are still stubborn holdouts. A woman has never been Treasurer or headed the Treasury or the Defence Department or been Chief of the Defence Force (or even head of one of the armed services).

But the most glaring – and certainly the most topical – exception to this seemingly inexorable march towards equality has been the severe partisan imbalance in the numbers of women in federal parliament.

Of the 75 women in federal parliament today just 19 are Liberals and two represent the National Party. Women are 46.3 per cent of the ALP’s representation but only 22.9 per cent of the Liberals’ and just 9.5 per cent of the Nationals.

The Liberal and National Parties do worse than any other parties in federal parliament when it comes to representation of women. In fact, not just worse. Far worse.

Every other party in the parliament has a significantly greater representation of women than the parties that currently form the federal government.

The Centre Alliance (formerly the Nick Xenophon Party) has just 33 per cent (which is still a lot higher than the government parties) but the Australian Greens, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and the Independents all come in at 50 per cent.

On any measure, the performance of both the Liberal and National Parties is poor but I propose to confine my comments to the Liberal Party for reasons that I hope will become evident.

The Liberal Party is frequently described as having a ‘woman problem’. I disagree. The Liberal Party does not have a woman problem. Rather, women have a problem with the Liberal Party.

The Liberal Party is frequently described as having a ‘woman problem’.

I disagree.

The Liberal Party does not have a woman problem.

Rather, women have a problem with the Liberal Party.

Women are finally seeing the Liberal Party for what it is – and which I will get to shortly – and as a result both women voters and women MPs are turning away.

The consequences of this for the Liberal Party itself and for our democracy are profound and I will spend some time exploring this.

But first let’s look more closely at women’s Liberal Party problem.

Women voters increasingly do not like the Liberals and are turning turned away.

According to a Newspoll conducted in October 2018 – the most recent I was able to find that provided a gender breakdown on voting intentions – 40 per cent of women were intending to vote Labor in the next federal election while just 34 per cent were opting for the coalition parties.[iii]

More and more women within the Liberal Party have decided they will no longer put up with it.

And they are voting with their feet: first Julia Banks resigned from the Liberal party in November last year, then Kelly O’Dwyer dramatically resigned her seat in January and, just two weeks ago, came the biggest defection of all when Julie Bishop, formerly deputy leader of the Party and the first Australian woman ever to serve as Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade, stood in the House, dressed in suffragette white, and announced that she, too, was leaving the parliament.

Julie Bishop being sworn in as Foreign Minister

For the first time in decades, Liberal Party women are voicing their frustration and anger at being overlooked for leadership roles (in the case of Julie Bishop), at being bullied and intimidated during leadership contests (in the case of Julia Banks and others) and at the double-standards when it comes to pre-selections (Craig Kelly got protected; Ann Sudmalis and Jane Prentice did not).

These women are sick to death of being pushed over, being pushed aside and being pushed out.

Their actions should be seen in the overall context of a Party that has continually expressed its implicit contempt for women in so many ways, and which these women have – masochistically, I would contend – not just endured but more often than not justified and rationalized.

Some of us looked on with amazement and disbelief as Liberal woman after Liberal woman, as recently as the middle of last year, continued to defend what many of us would have thought was the indefensible: the continual passing over of qualified women for pre-selections, the dumping of female sitting members, the failure to promote more women to the ministry and the Cabinet, and the continuing low tally of women MPs.

Yet, in the face of these realities, so many Liberal women insisted they were not feminists – implying that being pro-women was not necessary on their side of politics – and that quotas were not necessary because things were just fine.

Until, suddenly, they weren’t.

Liberal women for the most part are no longer defending what has been clear for quite some time: and that is that the hallmark of the modern Liberal Party is to discard its women members.

They are actually getting rid of the women!

They are actually getting rid of the women!

As a result, there are now fewer and fewer women MPs.

Prior to the 2016 election the Liberals had had 19 women in the House of Reps but they went into that election with only 17 because two retiring women members – Bronwyn Bishop and Sharman Stone – were replaced in their safe seats by men.

At that 2016 election six Liberal women lost their seats.

This would have given the party a total of just 11 women in the House had it not been for the fact that Julia Banks actually won the previously Labor seat of Chisholm, thereby bringing the total of Liberal party women in the lower house to 12.

(You’d think that having taken a seat from Labor Julia Banks would have been celebrated and honoured by the Liberal Party but as we recently learned, almost the opposite occurred. She was disparaged, described as ‘difficult’ and when she rose to deliver her speech of resignation from the Party on 27 November 2018 all but one of her male colleagues got up and left the chamber).

Over in the Senate there were eight women following the 2016 federal election, giving the Liberal Party a grand total of 20 women in the current federal parliament.

You have to go back to 1993 to find a parliament with fewer Liberal Party women.

That’s right, the Liberal Party has turned the clock back 25 years – a quarter of a century – when it comes to the representation of women in its ranks.

And it is about to turn it back even further.

After the 2019 federal election three of the 19 (down from 20 due to the defection of Julia Banks) Liberal Party women currently in parliament will not be returning.

And not because they have resigned: Senator Lucy Gichuhi has lost her winnable spot in South Australia, and Jane Prentice in Ryan and Ann Sudmalis in Gilmore lost their pre-selections to male candidates.

A further four will struggle to retain their seats: Lucy Wicks in the bellweather seat of Robertson, Michelle Landry in Capricornia, Nicolle Flint in Boothby and Sara Henderson in Corangamite.

Assuming all four lose their seats, the Liberal Party will have just 12 women in federal parliament.

And that is assuming that Julie Bishop is replaced by a woman. (I am also assuming that no new women are elected; given the recent preselection outcomes in Stirling and Gilmore that seems unlikely. Nor have I taken into account the Senate, apart from Lucy Gichuhi in South Australia).

Anne Summers with former Prime Minister Paul Keating in 1994

Meanwhile, across the aisle – most likely on the government benches – Labor is likely to reach its target of 50 per cent women at the 2019 election and increase its current number of 44 women MPs to as many as 47 members and senators.

The contrast between the two parties could not be starker.

But all this is not because the Liberal Party has a woman problem.

No. The Liberal Party has a man problem. And a merit problem. And a misogyny problem. And all three of these ‘M’s are inextricably connected.

It’s not just that the Liberal Party is not recruiting women, it is actually replacing women MPs with men. Think Bronwyn Bishop, Sharman Stone, Ann Sudmalis and Jane Prentice.

The Liberal Party is dispensing with merit as a criterion for selecting candidates and instead is putting clearly inferior men into seats that were or could be – and should be – occupied by women.

If the merit principle operated in the Liberal Party there would already be a larger proportion of women parliamentarians. It would happen automatically because merit is evenly distributed between the sexes. Instead the Liberal Party has made a virtue out of recruiting, pre-selecting and seeing elected scores of men with questionable qualifications, many of whom, as we are seeing currently, are ethically challenged and are certainly not serving this country well.

The merit principle supposedly used by the Liberal Party to select its candidates would be better described as the mirror principle. They are choosing people just like themselves, i.e. men.

And not just any men. The categories from which these men are drawn seems to be getting narrower. If present trends continue, the parliamentary Liberal Party will comprise mostly men whose backgrounds and qualifications are having worked for the IPA or served in the military.

So why are Liberal Party men spruiking merit but repudiating it in practice?

The answer is obvious: misogyny.

Misogyny, which I define as hostility to women, is expressed by wanting them excluded from places – be they boardrooms, or conclaves, or political parties – where decisions are made about the kind of country we are and can be.

Over the past two decades, the Liberal Party has acquired characteristics that are at odds with the vision, and principles, of its founder Sir Robert Menzies (which included equal representation of women within the party structure although this was slow to permeate into the parliamentary party).

The process of repudiating Menziesism began under John Howard but has not been challenged, let alone reversed, by any subsequent leaders.

First, the so-called ‘wets’ – MPs who were moderates on social and economic policy – were forced out; economic policy was turbo-charged to reflect a macho individualistic view of capitalism that disdained safety nets and other social protections; immigration and refugee policy were conflated and presented as aggressive border protection policies that were enforced with a never-before-seen brutality; education policy was corrupted by becoming a means of channeling public funds into already wealthy private schools at the expense of adequate education for the wider population; science was rejected; climate change denial became a defining mantra; homophobia and racism were adopted as ideological accoutrements and women began to be redefined as annoying special interests whose very presence was a massive inconvenience.

And this is why I see the current argument about whether or not the Liberal Party should introduce quotas as utterly irrelevant.

The proponents of quotas assume that the Liberal Party is concerned about the lack of women’s representation, that it wants to change. It doesn’t.

What I am arguing is that misogyny is now the hallmark of the Liberal Party. It is a badge worn with pride and it is not going to be surrendered. Kelly O’Dwyer recognised this when she told her Victorian party colleagues last November that the party was now widely regarded as ‘homophobic, anti-women, climate-change deniers’.

You got it in one, lady, they must have said back to her because two months later she was out of there. She saw that the party was not going to change. It does not want to and it won’t.

The Liberal Party is no longer liberal and has not been for a very long time.

Rather, it now resembles other conservative or, more accurately, right-wing parties which have undergone similar transformations.

The party it most closely resembles is the Republican Party in the United States which has undertaken a similar ideological transformation: it is also anti-education and anti science; it denies climate change, demonises immigrants and portrays immigration as a threat to national security; and is virulently homophobic and racist and which also celebrates its misogyny.

I am sure everyone here recalls the headlines following the US mid-term elections in November last year that heralded The Year of the Woman.

Record numbers of women were elected to Congress and, as a result, a record 127 women are now serving in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

But if you look a little more closely at the numbers, you will see almost all of these new women were Democrats.

Prior to the mid-terms there were 31 Republican women in Congress. Now there are just 21. Yes! The Republicans actually returned ten fewer women to Congress.

Their representation in the House has dropped from 25 to 13 although women won two additional Senate seats, increasing their number in the Senate from 6 to 8, thus giving the Republicans an overall total of 21.[iv]

The Democrats, on the other hand, increased their numbers in the Reps from 67 to 89, with their Senate representation unchanged at 17 women, giving them a total of 106 women in the 116th Congress.

A massive increase in one election.

Even so, these ‘record’ numbers need to be put into perspective. Women make up just 23.7 per cent of Congress, well below Australia’s 33.2 per cent and we are scarcely global leaders when it comes to women’s political representation.

It might have been the Year of the Woman but the US has a very long way to before it reaches parity with its female political representation.

Despite this, US politics have become a fascinating case study of gender in politics, especially as the country heads into its next Presidential election campaign.

The newly elected women have brought an unprecedented and refreshing diversity to Congress. They include the first Native American women elected to Congress, more African-American women including from states where they were not previously represented, a number of lesbians, the first openly bi-sexual Senator and others representing a range of experiences simply not found on the other side of politics.

As well, the diversity in age of the US Congress is something that most Australians, with our absurd focus on youth, would find astonishing.

The midterms saw elected to Congress the youngest ever woman in New York’s 29- year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (or AOC as this political rock star is universally known) – and the oldest, with Donna Shalala, a former Cabinet member in the Clinton administration and with a distinguished career in university administration, winning a seat in Florida at the age of 77.

There was much talk after the Democrats regained the House that Nancy Pelosi, at 78, was ‘too old’ to resume the Speakership, which position she had been the first woman to hold when she presided over the House from 2006 to 2010. She stared down those critics and regained the gavel in January this year, becoming the first person – and the only woman – to regain the position having held it once since Sam Rayburn in 1977.

After her early stunning performances outmaneuvering Donald Trump over the government shutdown and funding his wall, no one is now saying she is too old to do the job. Instead, I think we might be witnessing a widespread, even if grudging, acknowledgement that the experience, wisdom and what might be called corporate memory that age bestows is a very handy skill set to possess in American politics at the present moment.

And Pelosi, and Shalala, are far from the only two with such a skillset.

Although there is no current equivalent to Strom Thurmond who finally retired from the Senate in 2003 aged 100, having served for 48 years, a large number of US MPs are well above what would currently be seen as acceptable in Australia.

The oldest member of the US Congress was born in 1933; and a full 25 per cent of Senators are aged over 70, with 7 aged over 80. Despite AOC and the influx of younger MPs the average age of the current 116th Congress is 58.6 years – and is older than the 114th.

By contrast, the oldest member of the Australian parliament was born in 1944 – which, of course, makes him 75 this year.

Maybe the appointment of 77 year-old Ita Buttrose as Chair of the ABC will become a precedent, signaling our recognition of the value of utilizing the skillsets of older Australians.

Pelosi’s political skills are now on daily display as she leads the Democrats in figuring out how best to oust President Trump. Pelosi is an awesome example of a female leader who is comfortable with power and who is not afraid to wield it. Like Angela Merkel, another experienced political shape-shifter, Pelosi is showing what a woman exercising power and authority looks like. She is creating history and precedent and – let’s hope – paving the way for many others to follow.

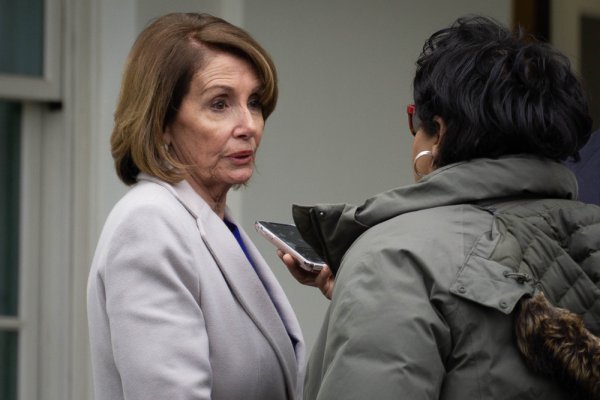

Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the House

And with an unprecedented six women now running for the Democratic nomination for President it does appear that American politics is being transformed.

When there was just a single woman candidate, the forces of sexism and misogyny – those people who cannot abide the idea of a woman in power – had it easy. They could direct all their hatred and bile with laser focus on that one woman. It won’t be so simple now.

The six women running are Senator Kamela Harris, from California, Senator Elizabeth Warren from Massachusetts, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand from New York, Senator Amy Klobucher from Minnesota, Representative Tulsi Gabbard from Hawaii and political outsider Marianne Williamson who is Oprah’s spiritual advisor and a self-proclaimed ‘bitch for God’.

They are all very different, in background, in political disposition, in the issues they are focusing on. Already, of course, there is considerable discussion and analysis of the ways in which each of them is being treated – in the media, especially – in ways that differ from how male candidates fare. The focus on their clothes, on their management styles, on their families.

It is early days of course. The primaries and caucuses do not begin for almost eleven months and the field is not yet fully formed. We can expect several more men to enter the race. We are in totally new territory with at least four women who are credible candidates. Will one of them make it all the way to become the nominee? We cannot yet say. All we can say that by having such a broad field of women, Presidential politics are changing. Let’s hope this is a precedent and not a one-off.

Of course if one of these woman makes it to the White House, she will become the first woman to occupy that position, and will bring America – finally – into the club of countries that has had a female leader.

Will she have to contend with a firestorm of misogyny? I expect so. Just one more burden on the shoulders of the person undertaking the hardest job in the world.

But in taking on both jobs – President and female trail-blazer – she will, in the word sof Julia Gillard the night she was deposed as Australia’s first female Prime Minister, make it easier for the next one, and the one after that.

It is clear that increasing women’s political representation is a manifestation of a certain type of politics, the kind of politics that is expansive and inclusive, politics that are small-l liberal or progressive. This is why the conservative side of politics in the US and in Australia has been slower to recruit women politicians, has been unwilling to adopt positive discrimination, using measures such as quotas, to guarantee increased number of women are elected and, now that they have lurched so far to the right, why these parties are actually ditching women.

These parties are about a different sort of politics.

You can argue that it is part of the contest between modernity and the reactionary politics of entrenched privilege or as AOC put it in a Tweet last month, ‘there is a wide gulf between the political centre and the moral centre’. And what is different now, she says, is that the moral centre is popular.

The kind of policies and politics that women tend to favour are now increasingly popular with voters.

This is something the Liberal Party either fails to understand or doesn’t care about. And this is why we are witnessing the phenomenon of moderate or centrist women Independents taking seats from them. It is a trend that is likely to accelerate as women who once might have found a political home in the Liberal Party now feel sufficiently alienated to run against that party.

A parliament with large numbers of women is a very different place from a parliament, or a chamber, where women either are not present at all – as in 1979 for instance – or are in such small numbers that they have very little influence.

But when women accrue political power, they use it differently and, as a result, they can transform society.

A study in 2018 of the almost 100 women who were running for office in the US mid-terms by the Washington-based Brookings Institution predicted that if the Democrats took control of the House of Representatives there would be ‘significant changes in the congressional agenda’.[v] Women candidates, on average, pushed issues such healthcare, gun control, climate change, preK-12 education and abortion to a far greater degree than male candidates.

And the Brookings prediction has turned out to be accurate. Already the new Congress is conducting hearings, writing legislation and developing other measures to ensure these issues are addressed. Many of them have not been touched since the Democrats last controlled the House. We can expect action on measures to expand opportunity, and to help families – especially on issues such as paid family leave, gun control and protecting the environment

Elizabeth Warren running for President with, among many progressive policies, an unprecedented – for a Presidential candidate – proposal for a national child care scheme.

As an economist she knows something that so many male economists apparently can’t see, and that is the economic power that is unleashed by facilitating women’s workforce participation.

A similar phenomenon is apparent here in Australia.

I don’t think it is drawing too long a bow to state that most – if not all – of the socially progressive legislation in the Australian parliament designed to improve the situation of women, children and families of the past forty years has been instigated or demanded by women.

The first federal legislation to federally fund childcare was legislated by the all-male Whitlam government but was the result of intense pressure from women in the ALP and feminists in organisations such as the Women’s Electoral Lobby.

Since then, such legislation has tended to be directly sponsored by women MPs.

Think of the ground-breaking Sex Discrimination Act of 1984 that was developed and shepherded through Parliament by Labor’s Senator Susan Ryan.

And let’s not forget the equally historic Paid Parental Leave laws of 2010 developed by Jenny Macklin, or the NDIS announced by Julia Gillard.

There have been cross-party efforts by women, most notably in 2005 when four Senators combined to have Parliament consider changes to the rules for the import of RU-486 the drug that provides an alternative to surgical abortion. Senators Judith Troeth (Liberal), Claire Moore (Labor), Fiona Nash (Nationals) and Lyn Allison (Australian Democrats) combined forces across the aisles to remove the power to prohibit the import of the drug from the Minister for Health, who at the time was Tony Abbott and who was resolutely refusing to allow it into the country. Instead, Parliament eventually passed the measure which gave that power to the Therapeutic Goods Administration, a less ideological decision-making body.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse is another, and very current and dramatic, instance of the transformative impact of a political decision by women

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse is another, and very current and dramatic, instance of the transformative impact of a political decision by women. Julia Gillard, Prime Minister, backed by her Attorney-General, Nicola Roxon, resisted extraordinary opposition and set in train an inquiry that has changed this country, and whose impact will be felt for many years.

Women have recognized that opportunities need to expand if they are to be able to fully participate in society. And women politicians have more often than not seen it as an obligation to help other women by finding legislative ways to achieve this. It wasn’t necessarily that male politicians were opposed to things such as child care or paid parental leave or affirmative action – though in many cases of course they were – it was just that it did not occur to most of them that such measures were needed.

Just as it took women assuming political power to insist on greater female representation on government boards, in government employment and everywhere decisions are made.

So, to conclude, increasing women’s political representation is not just about getting more women into politics.

It’s about expanding opportunities for women so they can participate equally in every area of society. That often entails providing services, such as childcare, or removing legal barriers, such as those that until 1966 required women to resign from employment when they married or which legislated that women could receive just 59 per cent of the male wage. Laws, in other words, were required.

Increasing women’s political participation is an essential step on the road to gender equality. Getting the representation and getting the laws are necessary. And once women are in office they tend to become – regardless of party – powerful agents of change for their gender.

Which is why, it seems, the conservative parties are getting rid of the women – because they don’t like where it is leading.  50/50 by 2030 Foundation team with Dr Anne Summers AO. (L-R: Mary Quinlan, Jane Alver, Virginia Haussegger, Anne Summers, Pia Rowe)

50/50 by 2030 Foundation team with Dr Anne Summers AO. (L-R: Mary Quinlan, Jane Alver, Virginia Haussegger, Anne Summers, Pia Rowe)

[i] Anna Hough, ‘Two parliamentary milestones for women – 75 years of women in the Commonwealth Parliament and Australia’s 100th female Senator’ Flagpost Parliamentary Library blog Parliament of Australia. Posted 20 August 2018

https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2018/August/Two_parliamentary_milestones_for_women

[ii] Politics and Public Administration Section, Commonwealth Parliamentary Library, Composition of Australian Parliaments by party and gender (by chamber), as at 15 January 2019

[iii] Peter Brent, ‘Yes, the Coalition does have a woman problem’ Inside Story 9 January 2019 https://insidestory.org.au/yes-the-coalition-does-have-a-woman-problem/

Table containing figures cited is at: https://www.pollbludger.net/bludgertrack2019/polldata.htm

[iv] Jennifer E. Manning, Senior Research Librarian Membership of the 115th Congress: A Profile. Congressional Research Service. Updated 20 December 2018

https://www.senate.gov/CRSpubs/b8f6293e-c235-40fd-b895-6474d0f8e809.pdf

Claire Hansen ‘116th Congress by Party, Race, Gender and Religion’ US News 3 January 2019

[v] Elaine Kamarck, Alexander R. Podkul and Nicholas W. Zeppos ‘The pink wave makes herstory: Women candidates in the 2018 midterms election’ Brookings blog Friday 1 June 2018 Brookings https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2018/06/01/the-pink-wave-makes-herstory-women-candidates-in-the-2018-midterm-elections/